A naturally replenished resource that is inexhaustible within a human lifespan characterizes a specific category of energy and material origins. These resources renew themselves over a relatively short period, distinguishing them from finite reserves that deplete over time. Solar radiation, wind currents, geothermal heat, flowing water, and biomass represent some examples of this resource category.

The utilization of these resources presents significant advantages, notably in mitigating environmental impact and promoting long-term sustainability. Unlike fossil fuels, the exploitation of such resources typically produces minimal or no greenhouse gas emissions, thereby reducing contributions to climate change. Historically, societies have harnessed these resources in various forms, ranging from windmills for grinding grain to watermills for powering machinery. Increased adoption of these resources strengthens energy security, diversifying supply and reducing reliance on volatile global markets.

Understanding the specific attributes and applications of various resources within this category is crucial for informed decision-making in energy policy and infrastructure development. Subsequent sections will delve into the specific technologies and practical considerations associated with harnessing particular resource types, exploring their potential contributions to a sustainable energy future.

Guiding Principles for Understanding Resource Renewal

The following recommendations are intended to assist in developing a more complete comprehension of resource renewal characteristics and their implications for practical application.

Tip 1: Emphasize Resource Replenishment Rate: The rate at which a resource regenerates is a critical factor. Assess if the rate of consumption is less than or equal to the natural replenishment rate to ensure sustainability. For instance, sustainable forestry practices ensure timber harvesting does not exceed the forest’s growth rate.

Tip 2: Consider Lifecycle Environmental Impact: Evaluate the total environmental consequences associated with resource extraction, processing, utilization, and disposal. Wind turbines, while harnessing renewable energy, require resources for manufacture and have end-of-life considerations.

Tip 3: Account for Geographic Variability: The availability and suitability of resources can vary significantly by location. Solar energy potential is substantially higher in regions with abundant sunlight compared to those with frequent cloud cover.

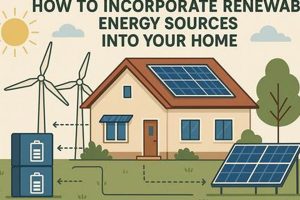

Tip 4: Investigate Technological Advancements: Technological innovation plays a pivotal role in enhancing the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of resource utilization. Improved battery storage solutions, for example, enable more reliable integration of intermittent sources into the electrical grid.

Tip 5: Analyze Economic Viability: Economic factors, including initial investment costs, operating expenses, and potential revenue streams, must be rigorously evaluated. Government incentives and carbon pricing mechanisms can influence the economic competitiveness of certain resource options.

Tip 6: Recognize the Intermittency Challenge: Certain types, such as solar and wind, are inherently intermittent. Strategies for managing this intermittency, such as energy storage or grid diversification, are essential.

Tip 7: Assess Land Use Implications: Large-scale deployment of these systems may require significant land areas. Consider the potential impacts on ecosystems and agricultural land, and prioritize strategies for minimizing land footprint.

Implementing these guidelines will support a more thorough understanding of resource renewal dynamics, allowing for better informed decisions regarding resource management and energy planning.

Subsequent discourse will explore the specific challenges and opportunities associated with transitioning to a predominantly renewably powered energy system.

1. Replenishment Rate

The concept of replenishment rate constitutes a fundamental criterion within the defining characteristics of resources classified as renewable. It dictates the long-term viability and sustainability of resource utilization, influencing both environmental impact and energy security considerations. The rate at which a resource is naturally restored directly determines its classification and management.

- Definition and Measurement

Replenishment rate refers to the speed at which a resource is naturally restored to its original state or availability after being utilized. Measurement units vary depending on the resource type, ranging from annual growth rates for biomass to recharge rates for aquifers. The rate is often quantified as a fraction or percentage of the total resource stock restored within a specific timeframe.

- Sustainability Thresholds

A resource is considered renewable only if its rate of consumption does not exceed its rate of replenishment. Exceeding this threshold leads to resource depletion, effectively transforming the resource from renewable to non-renewable. Sustainable forestry, for instance, requires harvesting timber at a rate slower than the forest’s regrowth capacity.

- Impact of Human Activities

Human activities can significantly influence the natural replenishment rate of certain resources. Over-extraction of groundwater, for example, can lower water tables and impair aquifer recharge. Similarly, unsustainable agricultural practices can deplete soil nutrients, reducing the capacity for biomass production.

- Technological Enhancements

Technological advancements can indirectly impact the effective replenishment rate by improving resource utilization efficiency. Enhanced solar panel efficiency reduces the overall resource demand required to generate a given amount of energy. Advanced water management technologies can improve irrigation efficiency, conserving water resources and supporting higher agricultural yields.

The connection between replenishment rate and defining resources as renewable is direct and crucial. Accurate assessment and responsible management of replenishment rates are paramount for ensuring long-term resource sustainability and avoiding unintended environmental consequences. Failing to maintain a balance between consumption and regeneration undermines the very definition of resource renewability.

2. Sustainability Metrics

Sustainability metrics serve as quantifiable measures assessing the long-term environmental, social, and economic impacts associated with various energy sources, materials, or processes. When evaluating whether a source meets the “renewable source definition,” these metrics offer a structured framework for determining its true sustainability. A source may be classified as renewable based on its natural replenishment rate, but a comprehensive analysis using sustainability metrics is essential to avoid overlooking potential negative consequences. For example, biomass, while technically renewable, may exhibit poor sustainability if its cultivation involves deforestation, intensive fertilizer use, or significant transportation emissions. These factors contribute to a larger carbon footprint and diminish its overall sustainability profile.

Several commonly used sustainability metrics include lifecycle assessment (LCA), carbon footprint analysis, water usage indicators, and land use assessments. LCA evaluates the cumulative environmental impacts throughout a product’s entire lifecycle, from raw material extraction to disposal. Carbon footprint analysis quantifies greenhouse gas emissions associated with a particular activity or product. Water usage indicators measure the quantity of water consumed and the potential impacts on water resources. Land use assessments analyze the impact on ecosystems and biodiversity. The application of these metrics enables a comparative analysis between different resources, revealing their respective strengths and weaknesses. Solar energy, for instance, typically exhibits a lower carbon footprint than fossil fuels, but its manufacturing process can involve the use of energy-intensive materials and rare earth elements. Wind energy has a relatively small land footprint compared to hydroelectric dams, but potential impacts on bird and bat populations must be considered.

In conclusion, sustainability metrics are indispensable for rigorously assessing resources in accordance with the “renewable source definition.” By incorporating these metrics into the evaluation process, a more holistic understanding of environmental, social, and economic implications emerges. This approach prevents the unintended promotion of options that, despite meeting the criteria of renewability, may entail substantial hidden costs or negative impacts. Future energy policies and resource management strategies should prioritize the integration of sustainability metrics to ensure genuine progress toward a truly sustainable energy future.

3. Environmental Impact

Environmental impact constitutes a critical dimension when evaluating whether a resource genuinely aligns with the “renewable source definition.” While a resource may naturally replenish itself, its extraction, processing, utilization, and disposal generate environmental consequences, requiring careful evaluation to determine its net sustainability.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The release of greenhouse gases is a primary concern. Although many options emit fewer GHGs than fossil fuels, some, such as biomass combustion, can still produce significant emissions, particularly if sourced unsustainably. Lifecycle assessments quantifying emissions from resource extraction to energy generation provide a comprehensive view.

- Land Use Change

Large-scale deployment of sources frequently necessitates considerable land areas, potentially displacing ecosystems and impacting biodiversity. Hydroelectric dams flood large areas, while solar farms and wind farms can alter habitats. Mitigation strategies include siting projects on degraded land or co-locating them with agricultural activities.

- Water Consumption and Pollution

Some technologies consume significant quantities of water or generate water pollution. Hydropower alters river flow regimes, impacting aquatic ecosystems. Geothermal energy production can release dissolved minerals into water sources. Closed-loop systems and careful wastewater treatment minimize these effects.

- Resource Depletion and Waste Generation

The manufacturing of renewable energy technologies requires raw materials, some of which are finite or extracted using environmentally damaging practices. Solar panels contain rare earth elements, and battery production generates hazardous waste. Sustainable material sourcing, recycling, and responsible waste management are essential for minimizing negative impacts.

Evaluating environmental impact is integral to determining whether a source truly aligns with the “renewable source definition.” A holistic assessment encompassing GHG emissions, land use change, water consumption, and resource depletion provides a more accurate reflection of its sustainability profile. Prioritizing strategies to minimize negative environmental effects ensures that the pursuit of renewable energy contributes to overall ecological health.

4. Resource Availability

The concept of “Resource Availability” is inextricably linked to the “renewable source definition,” serving as a pivotal determinant of a source’s practical viability and long-term sustainability. A resource may be inherently renewable, but its geographic distribution, accessibility, and temporal consistency profoundly influence its utility in meeting energy demands.

- Geographic Distribution

The spatial distribution of resources dictates their suitability for specific regions. Solar irradiance, wind patterns, geothermal gradients, and hydrological resources exhibit significant geographic variability. The deployment of solar technologies is optimized in areas with high solar insolation, while wind energy development concentrates in regions with consistent wind speeds. Geothermal potential is highest in tectonically active zones. Uneven geographic distribution necessitates energy transmission infrastructure to connect resource-rich areas with population centers, impacting the economic feasibility and environmental footprint of the energy system.

- Temporal Variability

The intermittent nature of certain resources presents challenges for grid stability and reliability. Solar energy production fluctuates diurnally and seasonally, while wind power output varies with weather patterns. Hydropower generation depends on precipitation levels and reservoir management. Addressing temporal variability requires energy storage solutions, grid diversification, and sophisticated forecasting techniques to ensure a consistent and reliable energy supply.

- Accessibility and Infrastructure

The ease with which a resource can be accessed and utilized is contingent upon existing infrastructure and technological capabilities. Offshore wind resources may be abundant but require specialized installation and maintenance vessels. Remote geothermal reservoirs necessitate advanced drilling technologies. The absence of adequate transmission infrastructure can constrain the development of resources located in sparsely populated areas. Investment in infrastructure development is essential to unlock the full potential of available sources.

- Resource Quality and Suitability

The inherent quality of a resource impacts its efficiency in energy conversion. Solar panel performance is influenced by spectral composition and ambient temperature. Wind turbine efficiency depends on wind speed and turbulence. Geothermal energy production varies with reservoir temperature and fluid chemistry. Hydropower generation is determined by water flow rate and head. Matching resource characteristics with appropriate conversion technologies maximizes energy output and economic viability.

In summation, while a resource might technically meet the “renewable source definition” through its natural replenishment, its practical application is significantly influenced by factors related to its availability. Geographic distribution, temporal variability, accessibility, and resource quality determine the extent to which these resources can effectively contribute to a sustainable energy mix. A comprehensive assessment of availability, alongside renewability, is critical for informed energy planning and policy decisions.

5. Technological Feasibility

The “renewable source definition,” while centered on natural replenishment, cannot be fully realized without considering “Technological Feasibility.” A resource, irrespective of its renewal rate, remains theoretical if the technology to harness it efficiently, reliably, and economically does not exist. Technological limitations directly impact the practical application of renewable sources, determining whether they can contribute meaningfully to energy supply or material production.

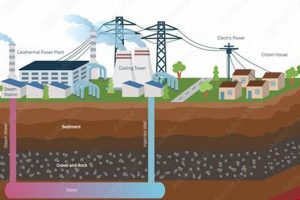

For instance, while geothermal energy represents a substantial renewable resource, its accessibility and utilization depend heavily on drilling techniques, power plant design, and materials science capable of withstanding extreme temperatures and corrosive fluids. Deep geothermal resources, offering immense potential, remain largely untapped due to technological hurdles in accessing and converting their energy. Similarly, harnessing wave energy, driven by persistent ocean forces, necessitates robust and efficient wave energy converters able to withstand harsh marine environments while delivering consistent power output. The successful deployment of floating offshore wind turbines hinges on advancements in mooring systems, turbine design, and electrical grid integration to overcome technical challenges associated with deep-water installations. The evolution of photovoltaic (PV) technology, continually improving efficiency and reducing costs, exemplifies how technological advancement directly enables wider utilization of solar energy.

In conclusion, technological feasibility acts as a critical gateway enabling the translation of renewable potential into tangible benefits. Overcoming technological barriers accelerates the adoption of these sources, driving the transition toward a sustainable future. Continuous innovation remains essential to fully unlock the potential of sources that meet the “renewable source definition”, ensuring they can contribute effectively to meeting global energy and material demands.

6. Economic Viability

Economic viability is a critical, often decisive, factor in determining whether a resource, despite meeting the “renewable source definition,” achieves widespread adoption. A resource that replenishes naturally but cannot be harnessed at a competitive cost relative to existing energy sources faces significant barriers to integration into the energy market. The economic feasibility of projects impacts investment decisions, policy support, and consumer acceptance. In essence, a resource’s renewability is only meaningfully valuable if its extraction, conversion, and delivery can be economically justified. This interplay between the “renewable source definition” and economic viability dictates the practical pathway to a sustainable energy future. For example, advanced geothermal systems (AGS), while tapping into a vast reservoir of renewable heat, currently face economic challenges due to high upfront drilling costs and the technological complexity of fracturing hot, dry rocks. Only continued technological innovation and cost reductions will render AGS economically viable on a large scale.

Government policies, such as feed-in tariffs, tax credits, and carbon pricing mechanisms, play a pivotal role in enhancing the economic attractiveness of sources adhering to the “renewable source definition.” Feed-in tariffs guarantee a fixed price for electricity generated from these sources, providing long-term revenue certainty for investors. Tax credits reduce the initial capital investment costs, making projects more financially accessible. Carbon pricing mechanisms, either through carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems, increase the relative cost of fossil fuels, thereby improving the competitiveness of emission-free resources. The success of solar power in many regions can be attributed, in part, to government incentives that reduced the cost of solar panels and made them economically attractive to consumers and businesses. Without these interventions, the higher upfront costs of solar technology might have hindered its widespread deployment despite its renewability.

In conclusion, the “renewable source definition,” while important, is insufficient on its own to guarantee widespread resource adoption. Economic viability serves as a crucial gatekeeper, determining whether these resources can compete effectively in the energy market and contribute meaningfully to a sustainable energy future. Technological innovation, policy support, and economies of scale drive down costs, thereby enhancing the economic viability and accelerating the deployment of sources that replenish naturally. Overcoming economic barriers is thus central to realizing the full potential of resources defined by their renewability.

7. Energy Security

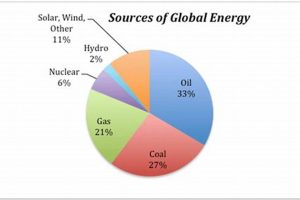

Energy security, defined as the uninterrupted availability of energy sources at an affordable price, is intrinsically linked to the “renewable source definition.” Reliance on finite fossil fuels introduces vulnerabilities associated with geopolitical instability, price volatility, and supply disruptions. Shifting towards resources that naturally replenish, as defined by the “renewable source definition,” strengthens national and global energy security by diversifying energy sources and reducing dependence on finite reserves concentrated in specific geographic locations.

- Diversification of Energy Sources

Sources that meet the “renewable source definition” inherently promote energy diversification. Reliance on a single energy source, such as oil, renders nations vulnerable to price shocks and supply disruptions arising from political instability or natural disasters in oil-producing regions. Integrating solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and biomass into the energy mix reduces dependence on any single source, enhancing resilience. For example, Germany’s Energiewende policy, promoting renewable energy, aims to reduce its dependence on imported fossil fuels, bolstering its energy independence.

- Reduced Geopolitical Vulnerability

Fossil fuel reserves are geographically concentrated, leading to geopolitical tensions and strategic dependencies. Nations lacking substantial fossil fuel resources become reliant on imports from a limited number of producing countries, subjecting them to political pressure and supply disruptions. The widespread availability of solar, wind, and other naturally replenishing sources diminishes this geopolitical vulnerability, as these resources can be harnessed domestically by most countries. China’s substantial investment in domestic solar manufacturing reduces its reliance on imported energy sources, increasing its strategic autonomy.

- Mitigation of Price Volatility

The prices of fossil fuels are subject to significant volatility due to geopolitical events, supply disruptions, and global demand fluctuations. Resources characterized by the “renewable source definition” offer greater price stability, as their costs are largely determined by upfront capital investments in infrastructure rather than fluctuating fuel prices. Once renewable energy facilities are operational, their operating costs are relatively low and predictable. Long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) for wind and solar energy provide price certainty for utilities and consumers, shielding them from the price volatility associated with fossil fuels. The Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) for many renewable technologies is now competitive with or lower than that of fossil fuels, further enhancing their economic appeal.

- Enhanced Grid Resilience

Decentralized energy systems based on resources that meet the “renewable source definition” enhance grid resilience. Distributed generation, such as rooftop solar panels, reduces reliance on centralized power plants and long-distance transmission lines, making the grid less vulnerable to widespread outages caused by natural disasters or cyberattacks. Microgrids powered by sources can operate independently from the main grid, providing a reliable power supply to critical infrastructure such as hospitals and emergency services during grid disruptions. The development of community-scale microgrids in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria exemplifies the potential of decentralized systems to enhance energy security and resilience in the face of extreme events.

In conclusion, the pursuit of energy security is inextricably linked to the adoption of resources. Diversifying energy sources, reducing geopolitical vulnerability, mitigating price volatility, and enhancing grid resilience are all benefits directly derived from transitioning towards energy systems powered by sources defined by their natural replenishment. As technological advancements continue to drive down the costs of these sources, their contribution to global energy security will only increase, fostering a more stable and sustainable energy future.

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Renewable Source Definition

The following questions and answers address common inquiries and misconceptions surrounding the concept of resources characterized by their natural replenishment. Clarity in understanding this definition is crucial for informed decision-making in energy policy and resource management.

Question 1: What precisely constitutes a renewable source as opposed to a non-renewable source?

The distinction lies in the rate of replenishment. Resources considered renewable replenish themselves naturally within a human timescale. Conversely, non-renewable resources, such as fossil fuels, deplete over time as their formation processes are exceedingly slow compared to their rate of consumption.

Question 2: Is biomass, derived from organic matter, invariably considered a renewable source?

While biomass originates from organic matter, its classification as a renewable source hinges on sustainable harvesting practices. If biomass is harvested at a rate exceeding its regeneration, or if its cultivation leads to deforestation or land degradation, it cannot be accurately categorized as renewable.

Question 3: Does the term “renewable source” inherently imply environmental sustainability?

Not necessarily. While these sources generally have lower environmental impacts than fossil fuels, their extraction, processing, and utilization can still generate environmental consequences. A comprehensive lifecycle assessment is essential to evaluate their true sustainability profile.

Question 4: How does the geographic distribution of resources impact their designation as truly renewable at a global scale?

The uneven distribution of solar irradiance, wind patterns, and geothermal potential influences the practical accessibility and economic viability of these resources in different regions. While a resource may be renewable in principle, its limited availability in certain areas can restrict its global contribution to sustainable energy systems.

Question 5: Are technological advancements crucial for realizing the full potential of sources characterized by their natural replenishment?

Absolutely. Technological innovation plays a pivotal role in enhancing the efficiency, reliability, and cost-effectiveness of resource utilization. Advancements in solar panel technology, wind turbine design, and energy storage solutions are essential for wider adoption and integration into the energy grid.

Question 6: How does the economic viability of technologies impact the overall contribution of sources meeting the “renewable source definition” to the global energy supply?

The economic competitiveness of resource technologies directly affects their deployment. Government policies, such as feed-in tariffs and tax incentives, play a significant role in leveling the playing field and promoting investment. Without economic incentives, these sources may struggle to compete with established, albeit environmentally less benign, energy sources.

A thorough understanding of these questions fosters a more nuanced perspective regarding resources defined by their renewability and their contribution to a sustainable future.

The subsequent section explores the long-term implications of transitioning towards a predominantly renewable energy-powered economy.

Conclusion

This exploration has emphasized that the “renewable source definition,” while conceptually straightforward, necessitates a multifaceted understanding for effective application. Natural replenishment alone is insufficient; sustainability metrics, environmental impact assessments, resource availability evaluations, technological feasibility analyses, economic viability projections, and energy security considerations all contribute to a comprehensive assessment. Discounting any of these factors risks mischaracterizing a resource’s true contribution to a sustainable energy future.

Continued diligence in research, development, and policy implementation remains paramount. A nuanced and rigorous approach to evaluating sources ensures that energy transitions are not merely symbolic but represent genuine progress toward a secure, sustainable, and equitable energy future. The implications of decisions made today will shape the environmental and economic landscape for generations to come.

![Basics: What is an Energy Source? [Explained] Renewable Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future | Clean & Green Power Basics: What is an Energy Source? [Explained] | Renewable Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future | Clean & Green Power](https://pplrenewableenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/th-100-300x200.jpg)