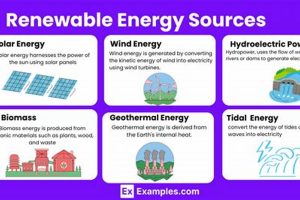

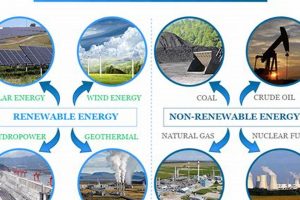

An energy source that is naturally replenished on a human timescale is considered sustainable. These sources are, by definition, not depleted when used. Examples include solar radiation, wind, geothermal heat, water flow, and biomass. The ability of these sources to regenerate distinguishes them from finite resources like fossil fuels and nuclear materials.

Reliance on such sustainable sources offers numerous advantages. It reduces dependence on imported fuels, mitigates greenhouse gas emissions, and fosters greater energy security. Historically, societies have utilized these methods, but recent technological advancements have significantly improved their efficiency and applicability for large-scale power generation. Their increasing adoption is crucial for addressing climate change and promoting a more sustainable energy future.

The subsequent sections will delve into the specific characteristics, technological advancements, and economic considerations associated with various forms of sustainable energy, highlighting their potential to transform the global energy landscape.

Maximizing the Utility of Replenishable Energy Sources

The following recommendations aim to enhance the efficient utilization of replenishable power sources, thereby optimizing their contribution to a sustainable energy infrastructure.

Tip 1: Diversify Energy Portfolio: Implement a strategy of integrating multiple forms. Reliance on a single type exposes systems to vulnerabilities arising from weather fluctuations or resource limitations. A blend of solar, wind, and hydro power provides resilience.

Tip 2: Invest in Energy Storage: Improve the consistency of supply using battery storage, pumped hydro, or thermal storage. These technologies mitigate the intermittent nature of several forms, ensuring a more reliable power grid.

Tip 3: Enhance Grid Infrastructure: A modern, resilient grid is essential for transporting power from remote areas to population centers. Smart grids, equipped with advanced sensors and control systems, optimize the distribution.

Tip 4: Promote Energy Efficiency: Reduce overall energy demand through energy-efficient buildings, appliances, and industrial processes. This lessens the burden on the grid and lowers the required scale of sustainable generation.

Tip 5: Incentivize Adoption through Policy: Governments can play a vital role in accelerating the transition to a sustainable future. Tax credits, feed-in tariffs, and carbon pricing mechanisms create favorable conditions for investment and deployment.

Tip 6: Support Research and Development: Continuous innovation is crucial for driving down costs and improving the performance of relevant technologies. Public and private investment in R&D ensures a sustained pipeline of breakthroughs.

Tip 7: Engage Local Communities: Build public support through education and outreach. Demonstrating the economic and environmental benefits will foster acceptance and accelerate project deployment.

Adopting these guidelines enables a more effective and economical transition to a future powered by inherently sustainable resources. Realizing this potential demands a concerted effort from policymakers, industries, and individuals alike.

The concluding section will summarize the primary advantages associated with these energy sources and highlight the ongoing need for further advancements.

1. Replenishment Rate

The replenishment rate is a foundational aspect in defining a renewable energy resource. It directly dictates whether a source qualifies as sustainable by determining if it can be renewed within a human timescale. A high replenishment rate signifies that the resource is quickly restored by natural processes, enabling continuous extraction without depletion. For example, solar irradiance exhibits an extremely rapid replenishment rate, with the suns energy constantly reaching Earth. Conversely, a resource with a replenishment rate exceeding practical timeframes, such as geothermal energy extracted from deep subsurface reservoirs, may face sustainability challenges depending on the extraction rate relative to the natural recharge.

The impact of the replenishment rate extends to technology deployment and environmental management. A fast replenishment rate necessitates efficient energy conversion technologies to capture and utilize the continuous influx effectively. Wind turbines, for instance, are designed to convert the kinetic energy of constantly replenishing wind into electricity. Moreover, awareness of the rate is crucial in managing the resource to prevent unintended depletion. Sustainable forestry practices ensure that biomass used for energy generation is replenished at a rate equal to or exceeding its consumption, mitigating deforestation. The replenishment rate is critical in evaluating the lifecycle and impacts of a considered source.

Understanding the correlation between the restoration pace and sustainability ensures the longevity of a resource. The replenishment rate is a key determinant of its potential and ecological impact, demanding careful management. Failure to account for natural restoration can lead to the depletion of a resource, undermining the promise of a sustainable energy future and blurring the line between resources categorized as replenishable and exhaustible. Therefore, assessment and proactive management of this facet are integral for harnessing nature effectively.

2. Source Sustainability

Source sustainability constitutes a critical element within the concept of a renewable energy resource. The viability of any energy source classified as replenishable hinges upon the long-term stability and regenerative capacity of its origin. If the method of harnessing an otherwise replenishable energy impairs its source, the resource loses its inherent sustainability. Deforestation provides a notable example. While biomass is technically renewable, unsustainable logging practices undermine the forests’ ability to regenerate, ultimately leading to a depletion of the resource and significant ecological damage. Therefore, true renewability demands that the extraction or conversion process does not compromise the long-term health and availability of the originating resource.

The intersection of source sustainability and resource renewability demands a holistic approach to energy management. It compels consideration of the entire life cycle of energy production, from initial resource extraction to final energy delivery. Geothermal energy, for instance, is often viewed as a reliable renewable source. However, the long-term sustainability of a geothermal plant depends on carefully managing extraction rates to prevent depletion of the underground heat reservoirs. In instances where extraction exceeds recharge, the heat source may diminish over time, rendering the plant unsustainable despite the earth’s vast geothermal reserves. Similarly, hydroelectric power generation is dependent on a consistent water supply. Construction of dams can significantly alter river ecosystems, impacting fish populations and sediment transport, thus affecting the long-term sustainability of the hydroelectric project.

In essence, a renewable energy resource is defined not solely by its regenerative capacity but equally by the preservation of its origin. This dual requirement necessitates vigilant environmental oversight, sustainable management practices, and continuous technological innovation to minimize impacts on source ecosystems. The sustainability of the source is fundamental to ensuring the viability and long-term benefits associated with energy production.

3. Environmental Impact

Environmental impact forms an intrinsic part of establishing the true sustainability and acceptability of any resource. While often perceived as inherently benign, energy resources classified as sustainable can still exert a range of ecological effects that must be rigorously evaluated when considering its definition.

- Land Use and Habitat Disruption

The physical infrastructure required for harnessing replenishable energy, such as solar farms, wind turbine arrays, and hydroelectric dams, frequently necessitates substantial land areas. This can lead to habitat fragmentation, displacement of wildlife, and alterations to local ecosystems. The construction of large-scale solar installations, for instance, can convert natural landscapes into industrial zones, impacting biodiversity and ecological functions. Similarly, wind farms may pose collision risks to birds and bats, while hydroelectric dams can disrupt riverine ecosystems and fish migration patterns. Thorough environmental impact assessments are therefore crucial to minimize and mitigate these potential ecological disturbances.

- Resource Extraction and Manufacturing

The production of technologies used to capture and convert replenishable energy often entails the extraction of raw materials and energy-intensive manufacturing processes. The mining of rare earth elements for solar panel production, for example, can generate significant environmental pollution, including water contamination and soil degradation. The manufacturing of wind turbine blades requires substantial amounts of energy and composite materials, contributing to carbon emissions and waste generation. A complete evaluation of true environmental effects includes the upstream impacts associated with the construction and deployment of these technologies.

- Waste Disposal and Recycling

As replenishable energy technologies reach the end of their operational life, the proper disposal and recycling of their components become increasingly important. Solar panels, for instance, contain hazardous materials, such as heavy metals, that require specialized handling to prevent environmental contamination. Wind turbine blades, often composed of composite materials, pose recycling challenges due to their complex composition and large size. The development of effective and sustainable waste management strategies is thus essential to minimize the environmental footprint of related infrastructure.

- Visual and Noise Pollution

Beyond direct ecological impacts, energy infrastructure can also generate aesthetic and noise pollution. Wind turbines, in particular, can be visually intrusive and generate audible noise, potentially affecting the quality of life for nearby residents. Large-scale solar installations may also alter the visual character of landscapes. Careful siting and design considerations are necessary to mitigate these potential impacts and maintain community acceptance.

Consideration of these environmental costs is essential for a holistic assessment of energy sources. By acknowledging and addressing these potential issues, more informed decisions can be made to maximize the benefits of these resources, while minimizing their impact. This nuanced assessment is paramount in ensuring that energy systems truly deliver a sustainable and environmentally sound future.

4. Resource Availability

Resource availability is a pivotal determinant in evaluating energy source renewability. The theoretical potential for an energy source to be perpetually available is contingent upon its actual existence and accessibility in sufficient quantities and locations. A resource may be naturally replenished, yet its practical applicability is restricted if geographically scarce or technologically challenging to harness. This intersection directly influences the viability and characterization of what constitutes a genuinely sustainable energy option.

- Geographic Distribution and Local Suitability

The uneven geographic distribution of many replenishable energy sources introduces constraints on their universal applicability. Solar irradiance, while globally present, varies significantly by latitude and climate, influencing the efficiency and economic viability of solar energy systems. Similarly, wind resources are concentrated in specific regions, often necessitating long-distance transmission infrastructure to connect these areas to population centers. Hydropower depends on the presence of suitable river systems and sufficient rainfall, limiting its potential in arid or flat regions. Therefore, local resource assessments are essential to determine the feasibility of utilizing a particular energy source in a specific location.

- Technological Accessibility and Extraction Costs

The ability to effectively harness replenishable energy sources is also constrained by the availability and cost of requisite technologies. While solar and wind technologies have become increasingly cost-competitive, their deployment still requires significant capital investment. Geothermal energy, while abundant in certain regions, often necessitates drilling deep wells and utilizing advanced extraction techniques, raising both economic and technological barriers. Furthermore, the efficiency of energy conversion technologies directly impacts the overall availability of usable energy. Low-efficiency solar panels or wind turbines reduce the amount of energy that can be extracted from a given resource, effectively limiting its practical availability.

- Temporal Variability and Grid Integration Challenges

Many forms exhibit temporal variability, presenting challenges for grid integration and energy supply reliability. Solar energy production fluctuates with daily and seasonal cycles, while wind power output varies with weather patterns. This intermittency necessitates the development of energy storage solutions, such as batteries or pumped hydro storage, to ensure a consistent energy supply. Furthermore, grid infrastructure must be adapted to accommodate the variable nature of energy, requiring investments in smart grid technologies and transmission capacity. Without adequate storage and grid integration capabilities, the temporal variability will limit the effectiveness of these variable sources.

- Competition with Other Resource Demands

The utilization of resources may encounter competition with other societal needs. Biomass, for example, can be used for energy production, but it also serves as a source of food, timber, and other essential materials. The sustainable use of biomass for energy requires careful management to avoid deforestation, land degradation, and competition with agricultural production. Hydropower projects can also conflict with other water uses, such as irrigation, drinking water supply, and navigation. Integrated resource planning is thus essential to balance the needs of various sectors and ensure the sustainable utilization of energy sources.

Accounting for the interplay of these factors is crucial for making informed decisions about energy policy and investments. A detailed understanding of the practical limitations affecting the use of energy resources will guide the development of realistic and sustainable energy strategies. By addressing challenges related to geographic distribution, technological accessibility, variability, and competing demands, societies can maximize the contribution of these sources to a secure and environmentally responsible energy future.

5. Technological Feasibility

Technological feasibility is a critical determinant in the practical application and definition of energy resources deemed sustainable. The mere existence of a replenishable source is insufficient; the ability to harness and convert that source into usable energy, utilizing current or realistically attainable technology, is paramount. Without viable technology, the potential for a resource to contribute to a sustainable energy mix remains theoretical.

- Energy Conversion Efficiency

The efficiency with which an energy source can be converted to electricity or other useful forms is a fundamental aspect of technological feasibility. Solar cells, for instance, are limited by their ability to convert sunlight into electricity. Wind turbines are similarly constrained by aerodynamic principles and material properties. Low conversion efficiency necessitates larger installations to achieve a given energy output, increasing land use and capital costs. Advances in materials science, engineering design, and energy storage are crucial for enhancing conversion efficiency and rendering such energy sources practically viable on a large scale.

- Infrastructure Requirements

The deployment of renewable energy technologies often requires significant infrastructure investments. Solar and wind farms necessitate extensive land areas and grid connections to transmit electricity to consumers. Hydropower projects demand the construction of dams and reservoirs, which can have significant environmental impacts. Geothermal plants require access to underground heat sources and specialized drilling equipment. The availability of suitable infrastructure, coupled with the cost of construction and maintenance, directly impacts the technological feasibility and economic viability of energy projects.

- Technological Maturity and Reliability

The maturity and reliability of energy technologies are critical considerations in assessing their suitability for widespread deployment. Solar and wind technologies have reached a relatively high level of maturity, with proven track records of performance and reliability. However, other technologies, such as wave energy converters and advanced geothermal systems, are still in earlier stages of development and face technological challenges that must be overcome before they can be widely adopted. Ensuring the long-term reliability and durability of energy systems is essential for minimizing downtime, reducing maintenance costs, and ensuring a stable energy supply.

- Storage and Grid Integration

The intermittent nature of many energy sources, such as solar and wind, presents challenges for grid integration and energy supply reliability. Energy storage solutions, such as batteries, pumped hydro storage, and thermal energy storage, are needed to smooth out fluctuations in energy supply and ensure a consistent power output. Furthermore, grid infrastructure must be adapted to accommodate the variable nature of energy, requiring investments in smart grid technologies and advanced control systems. The development and deployment of cost-effective energy storage and grid integration solutions are essential for enhancing the technological feasibility and overall viability of intermittent energy sources.

The technological feasibility of sustainable energy directly influences its potential to mitigate reliance on finite resources. Continuous innovation and investment in research are critical for overcoming technological barriers, improving efficiency, reducing costs, and ensuring the long-term reliability of sustainable energy systems. By addressing these technological challenges, the full potential of naturally replenished resources can be realized, contributing to a more secure and sustainable energy future.

6. Economic Viability

Economic viability is an indispensable criterion for evaluating the merit of a renewable energy resource. While a resource may be technically feasible and environmentally sound, its adoption hinges on its economic competitiveness relative to conventional energy sources. The capacity to generate energy at a cost that is competitive, or preferably lower, than existing alternatives is crucial for widespread deployment and long-term sustainability.

- Initial Capital Investment

The upfront capital costs associated with renewable energy projects often represent a significant barrier to entry. Solar farms, wind turbine installations, and geothermal plants require substantial investments in equipment, construction, and infrastructure. While these costs have declined significantly in recent years, they can still be higher than those associated with conventional fossil fuel power plants. Government subsidies, tax incentives, and innovative financing mechanisms can play a vital role in reducing the initial capital burden and making them more attractive to investors. For example, feed-in tariffs, which guarantee a fixed price for electricity generated from sustainable sources, provide revenue certainty and encourage investment.

- Operational and Maintenance Costs

Beyond initial capital investment, operational and maintenance (O&M) costs are an important determinant of the long-term economic viability. Energy sources generally have lower O&M costs compared to fossil fuel plants, as they do not require continuous fuel inputs. However, maintenance costs can still be significant, particularly for technologies such as wind turbines, which are subject to wear and tear from mechanical stress and environmental factors. Ongoing research and development efforts are focused on reducing maintenance costs, improving system reliability, and extending the lifespan of components to enhance economic competitiveness.

- Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE)

The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is a widely used metric for comparing the economic competitiveness of different energy sources. LCOE represents the average cost of electricity generation over the lifetime of a project, taking into account all costs, including capital, operating, and fuel costs, as well as financing costs. The LCOE of these sources has declined dramatically in recent years, making them increasingly competitive with conventional energy sources. However, LCOE values can vary significantly depending on location, resource availability, and project-specific factors. Therefore, a comprehensive economic assessment is essential for evaluating the economic viability of a particular project.

- Externalities and Social Costs

A comprehensive economic analysis must also consider the externalities and social costs associated with different energy sources. Conventional fossil fuel plants generate air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and other environmental damages that impose significant costs on society. These costs are often not fully reflected in the market price of electricity, leading to a market failure. Renewable energy sources, on the other hand, generate fewer externalities and can provide significant social benefits, such as reduced air pollution and improved public health. Incorporating these externalities into economic analyses can improve the economic competitiveness of these resources and promote a more sustainable energy system.

The long-term economic viability of an energy source is essential for its widespread adoption and integration into the energy mix. As technology costs continue to decline and environmental regulations become more stringent, energy is expected to play an increasingly important role in meeting global energy demands. Economic competitiveness, coupled with environmental benefits and technological advancements, will drive the transition towards a more sustainable and secure energy future.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following addresses common inquiries concerning the definition of a renewable energy resource, clarifying aspects of their nature, sustainability, and practical applications.

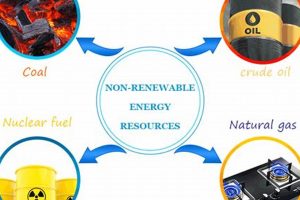

Question 1: What fundamentally distinguishes a renewable energy resource from a non-renewable one?

The core distinction lies in the replenishment rate. A renewable energy resource is naturally replenished on a human timescale, implying its usage does not lead to depletion. Non-renewable resources, such as fossil fuels, are finite and take millions of years to form, making their depletion inevitable with current extraction rates.

Question 2: Is biomass always considered a renewable energy resource?

Not necessarily. Biomass is only considered renewable when harvested sustainably. Unsustainable practices, like deforestation, undermine the regenerative capacity of forests, leading to resource depletion and ecological damage, thus negating its renewability.

Question 3: Can energy resources classified as sustainable have negative environmental impacts?

Yes, environmental impacts are possible. The infrastructure necessary for harnessing certain renewable energy sources can disrupt habitats and ecosystems. Additionally, the manufacturing processes involved in these technologies, and the eventual disposal of components, can have negative environmental consequences if not managed properly.

Question 4: How does geographic location impact the viability of a renewable energy resource?

Geographic distribution significantly influences the effectiveness. Solar resources are subject to fluctuations depending on latitude and local climate. Wind resources are constrained by the geographic locations. These factors affects the feasibility of harnessing them.

Question 5: What role does technology play in determining whether a source qualifies as “renewable?”

Technology plays a key role. Even if a source exists, the means to capture and convert energy into usable forms are critical. The maturity, efficiency, and cost of conversion technologies determine whether an energy resource can be effectively harnessed, influencing its practical viability.

Question 6: Why is economic viability a crucial consideration when evaluating a sustainable energy resource?

Economic viability is a necessity for widespread adoption. If the cost of generation is too expensive compared to conventional energy sources, it will be difficult to convince end users to switch.

In summary, a comprehensive understanding of energy resources extends beyond simple renewability, encompassing sustainability, ecological impacts, geographic constraints, technological feasibility, and economic viability.

The subsequent section will analyze the current trends in renewable energy adoption and forecast future developments in the sector.

Conclusion

The preceding exploration emphasizes that the definition of a renewable energy resource transcends simple replenishment. True sustainability encompasses environmental impact, geographical constraints, technological readiness, and economic feasibility. A holistic assessment, considering these interconnected factors, is paramount when evaluating energy options.

Recognizing this complexity is essential for shaping effective energy policies and investments. The path toward a truly sustainable energy future requires continuous innovation, rigorous environmental stewardship, and a commitment to economic viability. Only through such integrated efforts can the promise of renewable energy be fully realized.