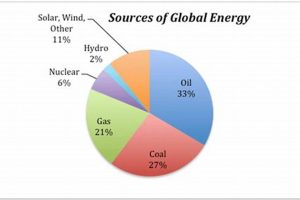

Energy resources that cannot be replenished at the rate they are consumed are classified as non-renewable. These resources are finite and their depletion raises significant environmental and economic concerns. A prime example is fossil fuels, encompassing coal, oil, and natural gas, which are formed over millions of years from the remains of organic matter.

The extensive utilization of finite energy supplies has propelled industrial development and modern conveniences; however, this dependence carries substantial consequences. The combustion of these resources releases greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change and air pollution. Historically, reliance on these resources has shaped geopolitical landscapes and economic strategies, underscoring the need for sustainable alternatives.

Understanding the characteristics and implications of these finite energy options is crucial for informing energy policy and promoting the adoption of sustainable practices. The subsequent sections will delve deeper into specific types, their environmental impacts, and the transition towards more sustainable energy solutions.

Guidance on Identifying Unsustainable Energy Practices

The following guidelines offer insights into recognizing energy consumption patterns that rely on finite resources, fostering informed decisions regarding energy usage.

Tip 1: Recognize the Carbon Footprint of Electricity Sources. Electricity generated from coal-fired power plants represents a significant contributor to carbon emissions. Evaluate the source of your electricity and consider options for renewable energy supply.

Tip 2: Assess Transportation Fuel Consumption. Vehicles powered by gasoline or diesel fuel are directly dependent on petroleum, a finite resource. Explore alternative transportation methods or fuel-efficient vehicles.

Tip 3: Understand the Environmental Impacts of Natural Gas Heating. While often considered cleaner than coal, natural gas remains a fossil fuel with greenhouse gas emissions. Investigate alternatives such as heat pumps or geothermal energy for heating needs.

Tip 4: Evaluate the Lifecycle of Plastics and Petrochemical Products. Many everyday items are derived from petroleum. Reducing consumption of single-use plastics and supporting sustainable manufacturing practices minimizes reliance on this resource.

Tip 5: Consider the Long-Term Viability of Nuclear Fission. While nuclear energy does not directly emit greenhouse gases, it relies on uranium, a finite resource, and presents challenges regarding waste disposal.

Tip 6: Support Policies Promoting Renewable Energy Development. Advocate for government and industry initiatives that prioritize investment in solar, wind, geothermal, and other sustainable energy technologies.

Tip 7: Conduct an Energy Audit to Identify Inefficiencies. Analyzing energy usage patterns within homes and businesses can reveal areas where consumption can be reduced, thereby lessening reliance on unsustainable sources.

Implementing these strategies contributes to a more sustainable energy future by reducing dependence on finite resources and mitigating environmental impacts.

The subsequent sections will focus on exploring alternatives to finite resources and strategies for transitioning to a sustainable energy economy.

1. Fossil Fuel Depletion

Fossil fuel depletion directly defines the concept of a non-renewable energy source. The finite nature of coal, oil, and natural gas means that their extraction and consumption surpass the rate at which they are naturally replenished. This disparity between consumption and natural regeneration forms the core characteristic of a non-renewable energy source. As reserves are extracted, the remaining supply diminishes, increasing scarcity and impacting cost. For instance, peak oil theory posits that oil extraction will reach a maximum point, after which production will decline, leading to increasing prices and potential economic disruption.

The rate of depletion is influenced by global energy demand, technological advancements in extraction methods, and geopolitical factors. Increased demand from industrializing nations accelerates depletion rates. While technological advancements, such as hydraulic fracturing (fracking), have expanded accessible reserves, they often come with environmental consequences and do not alter the fundamental issue of finite supply. The practical significance of understanding depletion lies in the need to transition to sustainable energy sources to ensure long-term energy security and mitigate the environmental impact of fossil fuel extraction and combustion.

Understanding the connection between fossil fuel depletion and the definition of non-renewable energy sources is crucial for crafting effective energy policies and driving innovation in renewable energy technologies. Facing the challenge requires acknowledging the limitations of fossil fuels and actively pursuing alternative energy systems to avert potential future energy crises and promote environmental sustainability. The depletion of these resources underscores the importance of proactive measures towards a more sustainable energy future.

2. Carbon Emissions Impact

The combustion of non-renewable energy sources, particularly fossil fuels, is a primary contributor to anthropogenic carbon emissions. This linkage between the utilization of resources that cannot be replenished and the subsequent release of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere constitutes a significant environmental concern. The dependence on coal, oil, and natural gas for electricity generation, transportation, and industrial processes directly results in substantial carbon emissions. These emissions, in turn, drive climate change, leading to rising global temperatures, altered weather patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events. The causal relationship between non-renewable energy and carbon emissions is well-established through scientific research and climate modeling.

The magnitude of carbon emissions associated with specific non-renewable sources varies. Coal, for example, is the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, releasing significantly more carbon dioxide per unit of energy produced compared to natural gas. The consequences of these emissions are far-reaching, including impacts on human health, ecosystems, and economic stability. Examples include the increased incidence of respiratory illnesses due to air pollution from coal-fired power plants and the displacement of coastal communities due to rising sea levels caused by climate change. Mitigation efforts aimed at reducing carbon emissions necessitate a shift away from reliance on non-renewable energy sources toward cleaner, sustainable alternatives.

In summary, the carbon emissions impact is an inextricable element of the definition and implications of non-renewable energy sources. Understanding this connection is essential for informing energy policy, promoting the development of renewable energy technologies, and mitigating the adverse effects of climate change. Addressing the challenge of carbon emissions requires a comprehensive approach that includes reducing energy consumption, increasing energy efficiency, and transitioning to a low-carbon energy economy. The reliance on resources that cannot be replenished carries significant environmental consequences through the release of carbon emissions, necessitating a global transition to sustainable energy systems.

3. Finite resource quantity

The inherent characteristic defining a non-renewable energy source is its finite quantity. This limitation dictates that these resources exist in fixed amounts, unable to be replenished within human timescales. This scarcity fundamentally differentiates them from renewable sources, shaping their utilization and long-term viability.

- Fixed Global Reserves

The total amount of fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, present on Earth is a fixed quantity. Geological processes forming these resources require millions of years, rendering them non-renewable within human lifespans. Extraction and consumption steadily deplete these reserves, eventually leading to exhaustion. The implications include increasing resource scarcity, rising energy prices, and geopolitical instability as nations compete for access to remaining reserves.

- Uneven Distribution

The geographical distribution of non-renewable resources is uneven, with certain regions possessing significantly larger reserves than others. This disparity creates dependencies and influences international relations. Countries lacking indigenous resources become reliant on imports, making them vulnerable to supply disruptions and price volatility. Furthermore, the control and exploitation of these resources can lead to conflicts and political tensions.

- Technological Limitations on Extraction

While technological advancements can improve extraction efficiency and access previously unreachable reserves, they do not alter the fundamental reality of finite quantity. Enhanced extraction methods, such as hydraulic fracturing, can extend the lifespan of existing reserves but often come with environmental consequences. Moreover, the energy required for extraction increases as reserves become more difficult to access, diminishing the net energy gain.

- Impact on Future Generations

The consumption of non-renewable resources has implications for future generations. Depleting these resources limits their availability for subsequent use, potentially hindering economic development and societal progress. Sustainable energy policies must consider the needs of future generations by promoting resource conservation and transitioning to renewable energy sources that can be replenished indefinitely.

The finite quantity of non-renewable resources represents a fundamental constraint on their long-term use. Addressing this limitation necessitates a shift towards sustainable energy practices that prioritize renewable sources and promote resource efficiency. Recognizing the implications of finite quantity is crucial for fostering a responsible and equitable energy future.

4. Geopolitical resource control

Control over the distribution and supply chains of non-renewable energy sources, like oil and natural gas, forms a critical dimension of global geopolitics. Nations possessing substantial reserves or strategic transit routes wield considerable influence on the international stage. This influence manifests in economic leverage, political alliances, and, in some instances, military interventions aimed at securing access to these vital resources. The concentration of non-renewable energy resources in specific regions creates dependencies for importing nations, rendering them susceptible to price fluctuations and supply disruptions dictated by resource-rich countries. For instance, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has historically influenced global oil prices through coordinated production policies, demonstrating the significant geopolitical power associated with control over this non-renewable resource. Furthermore, competition for access to these resources has fueled regional conflicts and international tensions, highlighting the inextricable link between energy security and global stability.

The strategic importance of non-renewable energy resources extends beyond direct control of reserves. Control over pipelines and maritime routes used for transporting these resources also confers significant geopolitical power. Nations controlling key transit points can exert influence over the flow of energy, impacting the economies of both producer and consumer nations. Examples include the strategic significance of the Strait of Hormuz for global oil shipments and the ongoing disputes over gas pipelines in Eastern Europe. These control points act as chokepoints, capable of being leveraged for political or economic gain. The pursuit of energy security often involves nations seeking to diversify their energy sources and establish alternative supply routes to reduce dependence on any single supplier or transit route. Such diversification efforts aim to mitigate the risks associated with geopolitical resource control and enhance national resilience.

In summary, geopolitical resource control is a defining characteristic of the non-renewable energy landscape, shaping international relations and influencing global power dynamics. The uneven distribution of resources, coupled with the strategic importance of supply routes, creates dependencies and vulnerabilities. Understanding the complexities of geopolitical resource control is essential for navigating the challenges of energy security and promoting a more stable and equitable global order. The imperative to transition towards renewable energy sources, less concentrated geographically and less susceptible to geopolitical manipulation, emerges as a critical strategy for mitigating these risks and fostering a more sustainable and secure energy future.

5. Environmental degradation risk

The utilization of non-renewable energy sources carries a substantial risk of environmental degradation. This risk encompasses various detrimental effects on ecosystems, human health, and the overall ecological balance, directly stemming from the extraction, processing, and combustion of these finite resources.

- Habitat Destruction and Biodiversity Loss

The extraction processes associated with non-renewable energy often involve large-scale habitat destruction. Mountaintop removal coal mining, for instance, obliterates entire ecosystems, leading to biodiversity loss and disrupting ecological processes. Oil and gas drilling operations can fragment habitats, impacting wildlife migration patterns and breeding grounds. These disruptions can have cascading effects throughout the food chain, threatening the stability of ecosystems.

- Air and Water Pollution

Combustion of fossil fuels releases pollutants into the atmosphere, contributing to air pollution and respiratory illnesses. Sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, byproducts of burning coal and oil, contribute to acid rain, harming forests and aquatic ecosystems. Accidental spills and leaks during the extraction and transportation of oil can contaminate water sources, posing risks to human health and aquatic life. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico exemplifies the devastating consequences of such incidents.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Change

The primary driver of climate change is the emission of greenhouse gases from the combustion of fossil fuels. Carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide trap heat in the atmosphere, leading to rising global temperatures, altered weather patterns, and sea-level rise. Climate change exacerbates existing environmental stresses, increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, such as hurricanes, droughts, and floods. These events can cause widespread damage to ecosystems, infrastructure, and human communities.

- Waste Generation and Disposal

The nuclear fuel cycle, while not directly emitting greenhouse gases during electricity generation, produces radioactive waste that requires long-term storage. The safe disposal of nuclear waste is a complex and challenging issue, with potential risks of environmental contamination. Mining operations for coal and uranium generate significant amounts of waste rock and tailings, which can contain hazardous materials that leach into the environment if not properly managed.

These facets of environmental degradation risk underscore the significant environmental costs associated with reliance on non-renewable energy sources. The long-term consequences of these risks necessitate a transition to sustainable energy alternatives to protect ecosystems, mitigate climate change, and safeguard human health. The imperative to minimize environmental degradation serves as a compelling argument for prioritizing renewable energy sources and promoting sustainable energy practices.

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Finite Energy Resources

This section addresses common inquiries concerning resources unable to be replenished at the rate of consumption, providing clarity on their nature and implications.

Question 1: What distinguishes a non-renewable energy source from a renewable one?

Non-renewable energy sources exist in finite quantities, unable to be replenished within human timescales. Renewable energy sources are naturally replenished, such as solar, wind, and hydropower.

Question 2: What are the primary examples of non-renewable energy sources?

The primary examples include fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) and nuclear fission, which relies on uranium, a finite resource.

Question 3: What are the environmental consequences associated with the use of non-renewable energy sources?

The combustion of fossil fuels releases greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change and air pollution. Extraction processes can cause habitat destruction and water contamination.

Question 4: How does the depletion of non-renewable energy sources impact the economy?

As reserves deplete, the cost of extraction increases, leading to higher energy prices. Dependence on imports can create economic vulnerabilities for nations lacking indigenous resources.

Question 5: Does nuclear energy qualify as a renewable energy source?

No, nuclear energy, specifically nuclear fission, relies on uranium, a finite resource extracted from the Earth. While nuclear fusion holds promise, it is not yet commercially viable.

Question 6: What are the alternatives to non-renewable energy sources?

Alternatives include solar energy, wind energy, geothermal energy, hydropower, and biomass, all of which are renewable and sustainable energy options.

Understanding the characteristics and implications of finite energy options is crucial for informing energy policy and promoting the adoption of sustainable practices.

The subsequent sections will delve deeper into specific renewable energy options and strategies for transitioning to a sustainable energy economy.

Non-Renewable Energy Source Realities

This exploration has illuminated the characteristics and ramifications of selecting that which is not a renewable energy source. Fossil fuels and nuclear fission, limited in supply and environmentally impactful, contrast sharply with sustainable alternatives. Their continued dominance presents significant challenges to global climate stability and long-term resource security.

The imperative to transition away from reliance on options that are not renewable energy sources demands immediate and sustained action. Investing in renewable technologies, implementing energy efficiency measures, and enacting supportive policies are critical steps toward a sustainable energy future. The consequences of inaction will be borne by future generations.

![Basics: What is an Energy Source? [Explained] Renewable Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future | Clean & Green Power Basics: What is an Energy Source? [Explained] | Renewable Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future | Clean & Green Power](https://pplrenewableenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/th-100-300x200.jpg)