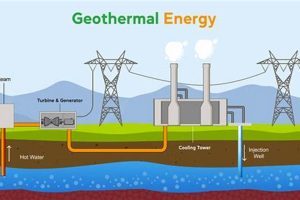

Materials that replenish naturally and within a relatively short timeframe constitute a category of sustainable assets. Examples include solar energy, derived from the constant irradiation of the sun, and wind power, which harnesses the movement of air masses driven by solar heating of the earth. Geothermal energy, originating from the earth’s internal heat, and hydropower, utilizing the gravitational force on flowing water, also fall into this category.

The significance of these assets lies in their potential to mitigate environmental impact by reducing reliance on finite reserves, such as fossil fuels. Their adoption contributes to decreased carbon emissions, contributing to strategies aimed at addressing climate change. Historically, simpler applications of these principles, like windmills and watermills, provided power for basic tasks. Modern technological advancements have significantly increased the efficiency and scale of energy generated from these sources.

The following sections will further examine the characteristics, advantages, and challenges associated with different types of these assets, and how they are integrated into various sectors to meet current and future energy demands.

Maximizing the Utility of Replenishable Assets

The following guidelines provide insights into optimizing the application of assets that can be naturally replenished, enhancing sustainability and resource management.

Tip 1: Prioritize Long-Term Sustainability Assessments: Before investing in any source, conduct a comprehensive evaluation of its long-term environmental and economic viability. Consider factors such as ecological impact, lifecycle costs, and resource availability projections.

Tip 2: Implement Diversification Strategies: A diversified portfolio of assets that can be naturally replenished reduces vulnerability to fluctuations in resource availability and market dynamics. Combine sources like solar, wind, and hydropower to enhance energy security.

Tip 3: Invest in Advanced Storage Technologies: Mitigate the intermittency of assets that can be naturally replenished, such as solar and wind, by integrating advanced energy storage solutions. This includes battery storage, pumped hydro storage, and thermal energy storage.

Tip 4: Support Research and Development: Technological advancements are critical for improving the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of assets that can be naturally replenished. Advocate for and invest in research and development initiatives that focus on innovation in this domain.

Tip 5: Promote Policy Frameworks: Encourage the development and implementation of supportive policy frameworks that incentivize the adoption of assets that can be naturally replenished. This includes feed-in tariffs, tax incentives, and renewable energy mandates.

Tip 6: Emphasize Grid Modernization: Upgrade and modernize electrical grids to accommodate the integration of distributed generation from assets that can be naturally replenished. Smart grid technologies enhance grid stability and reliability.

These strategies aim to maximize the potential of assets that can be naturally replenished, fostering a more sustainable and resilient energy future.

The subsequent sections will elaborate on the practical applications and future prospects of these guidelines.

1. Sustainability

The inherent connection between sustainability and assets that naturally replenish is a fundamental principle in responsible resource management. Assets that naturally replenish are sustainable only when their utilization rate does not exceed their natural regeneration rate. If consumption outpaces renewal, the resource, regardless of its initial nature, becomes effectively non-renewable. The efficient use of sources, such as forests, emphasizes this relationship. Sustainable forestry practices ensure continuous timber yield, preventing deforestation and ecosystem degradation. Conversely, unsustainable logging transforms forests into non-renewable assets.

Sustainability’s importance as a component of assets that naturally replenish extends beyond mere availability. It encompasses environmental, economic, and social dimensions. Environmentally, sustainable practices minimize pollution, preserve biodiversity, and protect ecosystems. Economically, they foster long-term stability by ensuring resource availability for future generations. Socially, they promote equitable access to resources and contribute to community well-being. For instance, well-managed fisheries exemplify this holistic approach. Sustainable fishing quotas prevent overfishing, maintaining fish populations, protecting marine ecosystems, and supporting the livelihoods of fishing communities.

Understanding the link between sustainability and assets that naturally replenish has practical significance in shaping resource management policies and practices. It informs decisions regarding resource allocation, consumption patterns, and technological investments. Prioritizing renewable energy sources, implementing sustainable agriculture, and promoting responsible water management are all examples of practical applications. Ultimately, sustainable management ensures that assets that naturally replenish can continue to contribute to human well-being without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. The key challenge lies in balancing immediate needs with long-term considerations and effectively implementing sustainable practices across diverse sectors.

2. Replenishment rate

The rate at which a material or energy source restores itself is a critical factor in determining its viability as a constantly renewed asset. It influences the scale and sustainability of its exploitation.

- Resource Availability Planning

The planning and management of resources depend heavily on an accurate assessment of their renewal velocity. Consider timber: while forests are often cited as constantly renewed, the speed at which trees mature determines the sustainable harvesting rate. Over-extraction, exceeding the replenishment rate, leads to deforestation and transforms this theoretically continuously renewed asset into a finite one. Similarly, groundwater extraction must not surpass the aquifer’s recharge rate to prevent depletion.

- Energy Production Feasibility

The energy generation potential of a resource is directly proportional to its capacity to replenish. Solar irradiance, a constantly renewed source, arrives at a consistent rate, enabling predictable energy capture through photovoltaic systems. Contrastingly, geothermal power relies on heat diffusion from the Earth’s core, a far slower process. While vast, the rate of heat extraction must be managed to ensure long-term source availability. Energy harvesting must match its source’s capacity to replenish to ensure the operation’s extended viability.

- Ecological Impact Mitigation

The effect that use has on the environment is also linked to the renewal velocity. A fast rate may mean a resource can endure more intense usage without lasting harm. Biomass energy, derived from fast-growing plants, minimizes carbon emissions if the plants regrow quickly, absorbing CO2. But, slow regrowth or unsustainable harvesting practices reverse this benefit. The speed at which an asset comes back affects how its usage alters surrounding natural systems.

- Economic Viability

For renewable assets, the rate impacts the long-term economic prospects. The initial expense of equipment to gather or take from a resource must be weighed against the predictable rate at which it comes back. Investment in wind turbines is justified by the constant availability of wind, a resource that constantly replenishes. However, in regions with low or inconsistent wind speeds, the economic return diminishes. If the resource doesn’t refill itself quick enough, then the initial investment might not pay off. If the rate of renewal is slow or uncertain, it affects the ability of those who own it to take advantage of the opportunity.

In essence, the value and potential of any resource touted as perpetually available are intrinsically tied to its rate of re-establishment. Understanding and managing this rate is paramount for ensuring long-term sustainability and realizing the full benefits of using constantly renewed resources.

3. Environmental impact

The extent of environmental consequences is a critical factor when evaluating the true sustainability of assets that naturally replenish. While often presented as ecologically benign alternatives to finite reserves, all energy and material extraction methods carry some degree of environmental cost. A thorough assessment of these impacts is essential for informed decision-making.

- Land Use and Habitat Disruption

The infrastructure required to harness sources, such as solar and wind, necessitates significant land use. Large-scale solar farms can displace natural habitats, while wind turbine installations may disrupt bird migration patterns and bat populations. Hydropower dams alter river ecosystems, impacting fish migration and sediment transport. Sustainable deployment strategies must minimize habitat fragmentation and ecological disruption through careful site selection and mitigation measures.

- Resource Depletion and Waste Generation

The manufacturing of renewable energy technologies relies on finite resources, including rare earth minerals. The extraction and processing of these materials can have substantial environmental consequences, including habitat destruction and water pollution. Furthermore, the disposal of end-of-life components, such as solar panels and wind turbine blades, poses a waste management challenge. Circular economy principles, emphasizing recycling and reuse, are vital for mitigating these impacts.

- Water Consumption and Pollution

Certain renewable energy technologies, particularly concentrated solar power and biofuel production, can be water-intensive. Water scarcity is an increasing concern in many regions, and the diversion of water for energy production can exacerbate these issues. Furthermore, biofuel production can lead to water pollution from fertilizers and pesticides. Sustainable water management practices are crucial for minimizing the environmental footprint of these technologies.

- Visual and Noise Pollution

The aesthetic impact of large-scale installations, such as wind farms and solar arrays, can be a concern for local communities. Noise pollution from wind turbines can also be a nuisance. Careful planning and community engagement are necessary to address these concerns and minimize the impact on the quality of life.

A comprehensive understanding of the environmental consequences of harvesting assets that naturally replenish is essential for promoting genuinely sustainable energy and material systems. While these sources offer significant advantages over finite reserves, it is crucial to acknowledge and mitigate their potential environmental drawbacks through responsible planning, technological innovation, and robust regulatory frameworks. A life-cycle assessment approach is vital for comparing various energy options and selecting the most environmentally sound solutions.

4. Economic viability

The economic viability of sources that naturally replenish is a crucial determinant of their widespread adoption and long-term sustainability. Cost-effectiveness, return on investment, and competitiveness with conventional energy sources all influence the feasibility of harnessing these resources. This necessitates a thorough evaluation of the entire lifecycle, from initial investment to operational expenses and eventual decommissioning.

- Initial Investment Costs

The upfront costs associated with establishing facilities to harness sources that constantly replenish, such as solar farms or wind turbine installations, often represent a significant barrier to entry. These costs encompass equipment procurement, site preparation, and grid connection infrastructure. While government incentives and technological advancements can help reduce these initial expenses, they remain a critical factor in determining the economic feasibility of project development. For instance, the construction of a geothermal power plant involves substantial drilling and infrastructure costs, requiring careful financial planning and risk assessment.

- Operational and Maintenance Expenses

The ongoing costs associated with operating and maintaining facilities that use assets that naturally replenish impact their long-term profitability. These expenses include routine maintenance, equipment repairs, and personnel costs. While some sources, such as solar, require relatively low maintenance, others, like biomass power plants, may have higher operational costs due to fuel procurement and processing. Effective cost management strategies are essential for ensuring the economic sustainability of these projects throughout their operational lifespan.

- Energy Storage and Grid Integration Costs

The intermittency of many sources necessitates the implementation of energy storage solutions and grid integration infrastructure. Battery storage systems, pumped hydro storage, and smart grid technologies add to the overall cost of employing assets that naturally replenish. These expenses must be carefully considered when assessing the economic competitiveness of these sources compared to conventional alternatives that offer dispatchable power generation. Investment in advanced storage and grid management technologies is crucial for enhancing the reliability and affordability of resources that constantly restore themselves.

- Revenue Generation and Market Competitiveness

The ability of renewable energy projects to generate revenue and compete in the energy market is a key determinant of their economic viability. Factors such as electricity prices, government subsidies, and carbon pricing policies influence the profitability of these projects. Feed-in tariffs, renewable energy credits, and carbon taxes can create a supportive market environment for these projects, encouraging investment and accelerating their deployment. The development of innovative business models and market mechanisms is essential for ensuring the long-term economic success of harvesting sources that constantly restore themselves.

In conclusion, the economic viability of resources that replenish naturally depends on a complex interplay of factors, including initial investment costs, operational expenses, energy storage costs, and revenue generation potential. While the upfront costs can be substantial, the long-term benefits of reduced fuel costs, lower carbon emissions, and increased energy security can make sources that constantly renew themselves a compelling economic proposition. Continued technological innovation, supportive government policies, and innovative business models are crucial for unlocking the full economic potential of these resources and accelerating the transition to a sustainable energy future.

5. Technological feasibility

The practical application of assets that are capable of natural replenishment is fundamentally contingent on existing technological capabilities. These capabilities dictate the efficiency, scalability, and economic viability of harvesting, converting, and distributing the energy or materials derived from sources that naturally regenerate. The presence or absence of appropriate technology directly influences which of these sources can be viably integrated into existing infrastructures.

- Energy Conversion Efficiency

The efficiency with which energy is converted from its naturally occurring form into usable electricity or heat is a critical factor. Solar photovoltaic technology, for instance, has seen substantial advancements, increasing the efficiency of converting sunlight into electricity. Higher efficiency reduces the land area required for solar farms, minimizing environmental impact and improving economic returns. Similarly, advancements in wind turbine design have increased the capture of wind energy, making wind power more competitive with conventional energy sources. Without ongoing advancements in energy conversion technologies, the potential of sources that naturally replenish remains limited.

- Grid Integration and Storage Solutions

The intermittent nature of some assets that naturally replenish, such as solar and wind, poses challenges for grid stability. Technological advancements in energy storage, including battery technology, pumped hydro storage, and thermal energy storage, are essential for mitigating this intermittency. Smart grid technologies, which enable real-time monitoring and control of energy flows, are also critical for integrating distributed generation from assets that naturally replenish into existing electricity grids. The absence of effective storage and grid integration solutions can limit the penetration of these sources into the energy mix.

- Material Science and Durability

The long-term performance and durability of the infrastructure used to harness materials that can be naturally replenished are critical for economic sustainability. Materials used in wind turbines, solar panels, and hydropower dams must withstand harsh environmental conditions for extended periods. Advancements in material science are leading to the development of more durable, corrosion-resistant, and efficient materials, extending the lifespan of renewable energy technologies and reducing maintenance costs. The availability of robust and reliable materials is essential for the widespread adoption of sources that naturally replenish.

- Accessibility and Infrastructure Development

The geographical accessibility of sources that naturally replenish and the availability of appropriate infrastructure are important considerations. Geothermal energy, for example, is only accessible in certain regions with suitable geological conditions. Hydropower development requires the construction of dams and reservoirs, which can have significant environmental impacts. The deployment of sources that replenish naturally often necessitates substantial infrastructure investments, including transmission lines, pipelines, and processing facilities. The presence of suitable infrastructure and accessible locations is crucial for realizing the potential of these sources.

The continued development and refinement of technologies related to energy conversion, grid integration, material science, and infrastructure are essential for expanding the feasible applications of assets that naturally replenish. Technological advancements not only improve the efficiency and reliability of these sources but also reduce their environmental impact and lower their costs, making them more competitive with conventional alternatives. As technology continues to evolve, the range of sources that can be viably integrated into sustainable energy and material systems will expand, contributing to a more resilient and environmentally responsible future.

Frequently Asked Questions About Resources Capable of Natural Replenishment

This section addresses common inquiries regarding sources that naturally renew themselves, clarifying misconceptions and providing factual information about their characteristics and applications.

Question 1: Is all biomass automatically considered a resource capable of natural replenishment?

No. While biomass derives from organic matter, its sustainability hinges on responsible management. If harvesting exceeds the regrowth rate, or if unsustainable land-use practices are employed, biomass can become a finite resource, negating its potential as a resource capable of natural replenishment.

Question 2: Does the initial cost of renewable energy infrastructure negate its classification as a resource capable of natural replenishment?

No. The high initial investment in infrastructure, such as solar panels or wind turbines, does not disqualify the underlying source as a resource capable of natural replenishment. Solar irradiance and wind are constantly available, even though capital expenditure is required to harness them.

Question 3: Are resources capable of natural replenishment inherently environmentally benign?

Not necessarily. While generally considered less harmful than finite reserves, every extraction and utilization method impacts the environment. Hydropower, for example, while drawing on a renewable water cycle, can disrupt aquatic ecosystems. Responsible planning and mitigation strategies are essential to minimize ecological damage.

Question 4: Can resource depletion occur even with a resource capable of natural replenishment?

Yes. Overexploitation can deplete even resources considered constantly available. Groundwater, though constantly replenished by rainfall, can be depleted if extraction exceeds the aquifer’s recharge rate, leading to water scarcity.

Question 5: Does technological advancement guarantee the sustainable use of resources capable of natural replenishment?

No. While technology enhances efficiency and expands the possibilities for harnessing these resources, it does not automatically ensure sustainability. Responsible governance, informed policies, and ethical practices are equally critical to preventing overexploitation and environmental degradation.

Question 6: Are all geographical locations equally suited for harvesting resources capable of natural replenishment?

No. The availability and suitability of sources that are constantly renewed vary significantly depending on location. Solar irradiance levels, wind speeds, and geothermal activity differ geographically, influencing the economic and technical feasibility of harnessing these resources. Site-specific assessments are crucial for optimal resource utilization.

In summary, a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing sustainability, environmental impact, and technological feasibility is crucial for effectively utilizing resources that naturally renew themselves. Careful planning and responsible management are essential to ensure the long-term viability of these sources.

The following section will explore policy implications and future trends related to resources that naturally renew themselves.

Conclusion

The exploration of “which resource is renewable” has elucidated the critical factors defining their true sustainability. These include the rate of replenishment, the environmental impact of extraction and use, the long-term economic viability, and the technological feasibility of harnessing these resources. A genuine understanding necessitates moving beyond the simplistic label of “renewable” to encompass the complexities of responsible resource management.

Ultimately, the responsible and sustainable integration of resources that naturally renew themselves into the global energy and material economy is a crucial step towards a more resilient future. Ongoing research, technological innovation, and informed policy decisions are essential to maximize the benefits while minimizing the environmental footprint. The success of this transition hinges on a commitment to long-term planning and a recognition that the term “renewable” is not a guarantee of sustainability, but rather an invitation to responsible stewardship.