Items that are utilized to achieve goals, whether physical materials, intellectual assets, or even intangible elements, exist alongside those that cannot be readily converted for productive purposes. Consider, for example, a deposit of iron ore that can be refined into steel, contrasted with barren land lacking the essential components for agricultural use.

The effective identification, allocation, and management of valuable assets is crucial for progress and sustainability. Throughout history, civilizations have prospered or declined based on their ability to leverage available advantages while minimizing dependence on limitations. Efficient management of useful components ensures long-term viability and economic stability.

The subsequent sections will delve into specific categories of these items, examining their characteristics, practical applications, and strategies for maximizing their potential while acknowledging inherent constraints.

Strategic Approaches to Valuable Assets and Limitations

The following guidelines offer a framework for understanding and managing advantages and inherent constraints in various contexts.

Tip 1: Conduct a Thorough Inventory. A comprehensive assessment of readily available advantages, encompassing both tangible and intangible forms, is crucial. For example, a business should analyze its equipment, intellectual property, and skilled workforce to identify underutilized elements.

Tip 2: Evaluate Potential Liabilities. Recognize constraints and assess their potential impact on objectives. This may include environmental limitations, regulatory hurdles, or scarcity of essential raw materials.

Tip 3: Optimize Utilization. Implement strategies to maximize the effectiveness of advantageous elements. This may involve process improvements, technology upgrades, or strategic partnerships to enhance productivity.

Tip 4: Mitigate Negative Impacts. Develop plans to minimize the adverse effects of inherent constraints. Diversification of supply chains, investment in alternative technologies, or adaptation of operational strategies are potential mitigation techniques.

Tip 5: Prioritize Sustainable Practices. Focus on responsible utilization that ensures long-term availability. Renewable energy sources, efficient water management, and waste reduction strategies contribute to sustainable resource management.

Tip 6: Invest in Innovation. Explore innovative solutions to overcome limitations and unlock new opportunities. Research and development efforts focused on alternative materials or processes can transform constraints into potential advantages.

Tip 7: Establish Clear Priorities. Focus efforts on assets and constraints that are critical to achieving objectives. A clear understanding of priorities allows for efficient allocation and strategic decision-making.

By diligently applying these principles, organizations and individuals can effectively leverage advantages and navigate obstacles, ultimately achieving greater success and sustainability.

The subsequent section will present case studies that illustrate these concepts in practical scenarios.

1. Availability

Availability directly impacts the distinction between assets and limitations. An entity only qualifies as a resource if it is accessible and obtainable for utilization. A vast mineral deposit located in an inaccessible region, for instance, presents itself more as a liability than an immediate economic asset due to the prohibitive costs and logistical challenges associated with its retrieval. Conversely, a readily available water source in an arid region transforms from a mere natural occurrence to a vital resource due to its accessibility and the immediate benefits it provides.

The degree of availability also dictates the strategic approach to its management. Readily available advantages warrant optimized utilization to maximize benefits, exemplified by efficient harvesting techniques for renewable energy sources like solar power. Conversely, assets with limited availability demand conservation strategies and the exploration of alternative solutions. Consider rare earth elements essential for various technological applications; their scarcity necessitates responsible mining practices, recycling initiatives, and research into substitute materials.

Ultimately, availability serves as a critical determinant in categorizing items as either advantages or restrictions. Understanding this connection is essential for effective resource management, strategic planning, and the development of sustainable practices. The practical significance lies in its capacity to inform decision-making, prioritize investments, and guide the responsible exploitation of advantages while mitigating the impact of limitations.

2. Accessibility

Accessibility, in the context of available assets and inherent constraints, fundamentally distinguishes between items that can be leveraged for benefit and those that remain practically unusable. Its presence or absence dramatically affects valuation and strategic deployment.

- Geographic Proximity and Infrastructure

Physical distance and supporting infrastructure significantly impact the usability of any item. An abundance of timber in a remote, roadless area, for example, holds substantially less immediate value than a smaller forest located near transportation networks and processing facilities. The presence of roads, railways, and ports effectively transforms the inaccessible into the accessible, turning potential advantages into tangible assets.

- Economic Feasibility

Even if physically reachable, certain advantages can remain economically inaccessible. The extraction of deep-sea minerals, while technologically possible, may be cost-prohibitive compared to land-based sources. Such economic barriers render these deep-sea deposits as long-term prospects rather than immediate items for exploitation. This situation necessitates a careful cost-benefit analysis to determine true value.

- Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

Legal and regulatory constraints frequently dictate whether an item can be classified as a usable asset. Water rights, land zoning laws, and environmental regulations can restrict or prohibit the exploitation of advantages, regardless of their physical abundance. A protected watershed, though a potential source of irrigation, may be legally off-limits, effectively rendering it a restriction in agricultural planning.

- Technological Capabilities

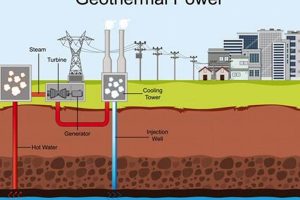

Technological limitations can significantly affect utilization. The presence of untapped geothermal energy may remain a constraint if the technology to efficiently harness it is unavailable or prohibitively expensive. Technological advancements, therefore, play a vital role in converting potential assets into actual, readily applicable sources of power or production.

In conclusion, assessing usability involves more than just physical existence. It requires careful consideration of geographic, economic, legal, and technological factors that collectively determine its true potential and place within strategic frameworks. These facets highlight the pivotal role of accessibility in distinguishing between advantageous elements and restricting factors.

3. Usability

Usability serves as a critical determinant in classifying an item as either a valuable asset or an inherent limitation. The mere presence of an entity does not automatically qualify it as a functional advantage; its capacity to be readily and effectively applied to a specific purpose is paramount. Without usability, potential benefits remain theoretical, and the item effectively functions as a non-advantage. For example, a newly discovered chemical compound, despite holding theoretical promise for pharmaceutical applications, remains a non-advantage until its synthesis can be reliably reproduced at scale and its effects safely administered to patients.

The assessment of usability necessitates a multi-faceted approach, considering factors such as technological feasibility, economic viability, and societal acceptance. An energy source, like nuclear fusion, may possess immense potential, but its current lack of technological usability, coupled with high initial investment costs and societal concerns, prevents it from being considered a widespread advantage. Conversely, solar energy, while not as energy-dense, enjoys increasing usability due to technological advancements in photovoltaic cells, decreasing costs, and growing public acceptance. This highlights how usability, or lack thereof, influences resource prioritization and investment strategies.

Ultimately, the practical significance of understanding usability in relation to advantageous elements and inherent constraints lies in its ability to inform strategic decision-making. By accurately assessing the usability of potential advantages, organizations and policymakers can allocate efforts and investments more effectively, focusing on solutions that offer tangible and timely benefits. Ignoring usability can lead to misallocation of efforts on initiatives that yield little practical return, whereas prioritizing it ensures that advantages are leveraged to their fullest potential, fostering innovation and sustainable progress.

4. Scarcity

Scarcity fundamentally alters the perception and management of items, transitioning them from readily available assets to strategically important commodities. This principle dictates that as the availability of a given item diminishes relative to demand, its value increases, and the imperative for efficient allocation becomes paramount. For example, arable land becomes a vital asset in densely populated regions, necessitating sustainable agricultural practices and innovative land-use strategies, whereas a similar quantity of land in a sparsely populated area might be considered a less critical asset.

The impact of scarcity extends beyond mere economic valuation; it drives innovation and dictates strategic priorities. The limited supply of rare earth minerals, crucial for various technological applications, has spurred research into alternative materials and recycling technologies. Furthermore, scarcity necessitates careful resource management and allocation decisions at local, national, and international levels. Water scarcity in arid regions, for instance, demands efficient irrigation techniques, water conservation policies, and, in some cases, international agreements on water resource sharing. The concept of non-advantages gains significance as scarcity increases for conventional items. It forces the consideration of unconventional alternatives and investments in technologies to utilize previously unusable or less desirable alternatives.

In conclusion, scarcity serves as a pivotal factor in determining the value and strategic importance of advantages and inherent constraints. It forces the adoption of efficient management practices, drives innovation, and underscores the need for careful resource allocation. Understanding this dynamic is critical for sustainable development and ensuring long-term resource availability in an increasingly resource-constrained world. Recognizing scarcity’s influence fosters proactive adaptation and the discovery of novel alternatives. The focus shifts to making “non advantages” viable, such as developing drought-resistant crops or harnessing previously untapped renewable sources.

5. Location

The geographical placement of advantageous elements and restricting factors profoundly influences their utility and economic significance. Position dictates accessibility, transportation costs, and exposure to various environmental and geopolitical factors, thereby shaping whether an item is considered a readily available advantage or an impractical limitation.

- Proximity to Markets and Infrastructure

Placement near population centers and transportation networks significantly enhances the value of advantageous elements. A mineral deposit located close to processing facilities and major transportation routes will be more economically viable than a similar deposit in a remote, inaccessible area. The presence of established infrastructure reduces transportation costs and facilitates efficient distribution, effectively converting a potential disadvantage into a usable asset. Conversely, valuable sources located far from markets and infrastructure remain as restrictions.

- Environmental Considerations

Geographic placement exposes items to specific environmental conditions that may either enhance or diminish their value. A region prone to frequent natural disasters, such as earthquakes or floods, may render even abundant advantages unusable due to increased risk and infrastructure damage. Conversely, a location with favorable climatic conditions, such as ample sunlight and consistent rainfall, can greatly enhance the value of agricultural advantages. These natural conditions can influence the sustainability and long-term viability of advantageous elements.

- Geopolitical Factors and Boundaries

Political boundaries and geopolitical considerations heavily influence the availability and usability of advantageous elements. Resources located within politically stable regions with favorable regulatory frameworks are more likely to be accessible and exploitable. Conversely, advantages located in areas of political instability, conflict zones, or disputed territories may be rendered unusable due to security risks and legal uncertainties. International trade agreements and tariffs can also significantly impact the economic viability of advantages based on their location.

- Specific Geographic Features

Geographic features, such as mountain ranges, coastlines, and river systems, play a critical role in determining the availability and accessibility of advantages. Mountainous terrain can impede access to mineral deposits or timber resources, while navigable rivers can facilitate transportation and trade. Coastal areas offer access to marine resources and shipping routes, but also present challenges related to coastal erosion and sea-level rise. The unique characteristics of a location, therefore, shape the opportunities and challenges associated with the utilization of items.

In summary, location serves as a crucial determinant in assessing the true value and usability of advantages and inherent constraints. Its interplay with market access, environmental factors, geopolitical considerations, and geographic features shapes the strategic decisions related to resource management and economic development. The analysis of location is vital for informed planning and sustainable utilization, ensuring that potential advantages are effectively leveraged and restrictions are appropriately addressed.

6. Potential

Potential, in the context of valuable assets and inherent limitations, represents the undeveloped capacity or latent possibilities inherent within both. It is the bridge connecting current limitations to prospective advantages, and understanding its dynamics is crucial for strategic planning and innovation.

- Technological Advancement

Technological innovation can transform limitations into assets by unlocking previously inaccessible potential. For example, the development of horizontal drilling techniques has allowed access to previously unreachable oil and natural gas reserves, converting a geological limitation into a viable advantage. Conversely, the potential for technological obsolescence must be considered when evaluating the long-term value of current assets. Investments in research and development can therefore unlock possibilities.

- Economic Viability

Economic conditions can dictate whether latent potential becomes a realized advantage. A mineral deposit may possess significant potential value, but unfavorable market prices or high extraction costs can render it economically unviable. However, shifts in market demand, technological improvements, or government incentives can alter the economic equation, transforming a limitation into a resource. Assessment of long-term projections is therefore essential for accurately gauging potential.

- Sustainability and Environmental Impact

The potential for environmental degradation can transform existing assets into liabilities. Overexploitation of renewable advantages, such as forests or fisheries, can lead to resource depletion and ecological damage, negating their long-term value. Conversely, investment in sustainable practices can unlock the potential for long-term resource availability and ecological resilience. Sustainable management transforms long-term liabilities into benefits.

- Human Capital and Innovation

The untapped potential of human capital represents a critical asset. Investing in education, training, and skills development can unlock individual and collective potential, leading to increased productivity, innovation, and economic growth. A lack of investment in human capital, conversely, can limit an item’s inherent value. Skilled labor turns non resources into advantages.

The successful identification and exploitation of potential requires a comprehensive understanding of technological trends, economic dynamics, environmental considerations, and human capital development. By strategically investing in these areas, organizations and nations can transform current limitations into future advantages, driving sustainable growth and long-term prosperity.

7. Transformation

The concept of transformation is central to understanding the dynamic relationship between valuable assets and inherent limitations. It represents the process by which items initially categorized as restrictions can be converted into exploitable advantages, and conversely, how previously reliable assets can degrade into liabilities.

- Technological Conversion

Technological advancements facilitate the conversion of previously unusable materials into valuable assets. The development of fracking technology, for example, enabled the extraction of natural gas from shale formations, transforming a geological limitation into a significant energy advantage. Similarly, advancements in recycling technology allow for the reprocessing of waste materials, converting a disposal issue into a secondary resource stream.

- Economic Repurposing

Shifting economic conditions can prompt the repurposing of assets previously deemed obsolete. Abandoned industrial sites, once considered liabilities due to environmental contamination and structural decay, can be redeveloped into commercial or residential spaces, creating economic value and mitigating environmental hazards. Economic incentives and strategic planning drive this change.

- Ecological Restoration

Environmental degradation can transform valuable ecosystems into liabilities, reducing biodiversity and ecosystem services. However, ecological restoration efforts can reverse this process, rehabilitating degraded lands and waterways and restoring their ecological and economic value. Reforestation projects, for example, can sequester carbon, enhance biodiversity, and provide timber and other products.

- Societal Adaptation

Changes in societal needs and preferences can lead to the transformation of perceived limitations into valuable resources. The growing demand for renewable energy has driven innovation in wind and solar power, converting previously underutilized sources of energy into viable alternatives to fossil fuels. Shifting societal values therefore affect asset valuation.

The capacity to transform limitations into advantages, and to safeguard existing advantages from degradation, is essential for sustainable development. By embracing innovation, fostering adaptability, and investing in ecological restoration, societies can maximize their access to critical items and ensure long-term resilience. The process demands continuous assessment and proactive management of items, recognizing the fluid nature of their classification.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following questions address common inquiries regarding the categorization, management, and strategic implications of valuable items and inherent constraints.

Question 1: What distinguishes a valuable item from an inherent constraint?

A valuable item is defined as any tangible or intangible entity that can be leveraged to achieve a specific objective or generate value. An inherent constraint, conversely, is any factor that impedes progress, limits options, or restricts access to desirable outcomes. The distinction hinges on the item’s utility and its impact on achieving goals.

Question 2: How does scarcity influence the valuation of advantages?

Scarcity directly elevates the value of advantages. As the availability of a particular advantage decreases relative to demand, its economic worth increases, and the imperative for efficient allocation and responsible management becomes more pronounced.

Question 3: What role does technology play in transforming restrictions into advantages?

Technological innovation is instrumental in converting limitations into viable advantages. Advancements in extraction techniques, material science, and energy production can unlock the potential of previously unusable items or overcome geographical and economic barriers.

Question 4: How can sustainability principles be integrated into items management?

Sustainability principles dictate that resources should be utilized in a manner that meets current needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own. This entails adopting responsible extraction practices, minimizing environmental impact, and investing in renewable alternatives to ensure long-term item availability.

Question 5: What is the significance of location in determining an items value?

Location significantly influences the accessibility, transportation costs, and exposure to environmental and geopolitical factors, thereby shaping its utility and economic significance. Advantages located near markets and infrastructure are generally more valuable than those in remote or unstable regions.

Question 6: How can potential be unlocked to convert non resources into advantages?

Unlocking potential requires strategic investments in research and development, education and training, and infrastructure development. By fostering innovation and building human capital, societies can transform limitations into valuable resources and drive sustainable growth.

Effective management of advantages and inherent constraints is crucial for economic development, environmental sustainability, and societal well-being. Understanding these key concepts is essential for informed decision-making and strategic planning.

The subsequent section will provide concluding remarks and highlight key takeaways from this exploration of valuable assets and inherent limitations.

Conclusion

The preceding discussion has illuminated the critical distinction between resources and non-resources, emphasizing the dynamic interplay of availability, accessibility, usability, scarcity, location, potential, and transformation. Understanding these factors is essential for effective strategic planning and sustainable development. The ability to identify, manage, and, crucially, transform limitations into advantages is paramount in an increasingly complex and resource-constrained world.

As global challenges intensify, a renewed focus on resource optimization and innovative solutions becomes imperative. Organizations and policymakers must prioritize responsible resource management, invest in technological advancements, and foster collaborative efforts to ensure long-term prosperity and resilience. The future hinges on the capacity to leverage resources wisely and convert apparent non-resources into valuable assets, securing a sustainable path forward for all.