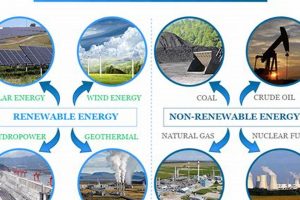

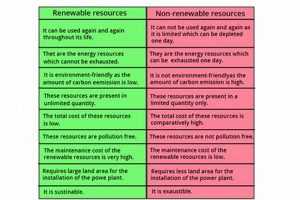

Resources that can be replenished naturally over time are considered sustainable. Examples include solar energy, wind power, geothermal energy, hydropower, and biomass. These sources contrast with finite resources, such as fossil fuels and minerals, which exist in limited quantities and are depleted by extraction and consumption.

The utilization of sustainable alternatives offers numerous advantages, including reduced greenhouse gas emissions, decreased reliance on foreign energy sources, and the potential for long-term economic stability. Historically, societies have relied on these types of energy, but the Industrial Revolution led to a significant shift towards the use of finite reserves. Growing environmental concerns are driving a renewed interest in and investment in these alternatives.

Understanding the characteristics and availability of different energy sources is essential for informed decision-making regarding energy policy and individual consumption habits. The following sections will delve into specific examples, exploring their potential and limitations as viable substitutes for conventional power generation.

Guidance on Identifying Replenishable Natural Assets

The following guidance assists in distinguishing between finite and naturally replenishing resources, crucial for sustainable practices.

Tip 1: Assess Origin and Replenishment Rate: Consider how the resource is generated. If it stems from geological processes spanning millions of years, such as oil formation, it is likely non-renewable. Conversely, resources like solar radiation or wind are continuously replenished.

Tip 2: Evaluate Consumption vs. Regeneration: Determine whether the rate of resource consumption exceeds its natural regeneration rate. For instance, deforestation surpasses forest regrowth in many regions, rendering timber a non-renewable commodity in those areas, despite its potential for replenishment.

Tip 3: Investigate Environmental Impact: The extraction and utilization of some sources entail significant environmental degradation, impacting their long-term availability. Excessive groundwater pumping can lead to aquifer depletion and land subsidence, diminishing its renewability.

Tip 4: Analyze Energy Input Requirements: Evaluate the energy required to harness a resource. If the energy input for extraction and processing is substantially high compared to the energy output, it may not be a sustainable energy alternative, even if it is technically renewable.

Tip 5: Consider Technological Advancements: Technological advancements can improve the efficiency of resource utilization. For example, advancements in solar panel technology can increase the amount of electricity generated from sunlight, enhancing the viability of solar energy as a sustainable option.

Tip 6: Check for Certification and Standards: Look for certifications or standards that verify the sustainable management of a resource. For example, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification ensures that timber comes from responsibly managed forests.

Tip 7: Understand the Resource Lifecycle: A comprehensive understanding of the lifecycle, from extraction to disposal, helps to assess its overall sustainability. Recycling programs can significantly extend the lifespan of materials and reduce the need for new resource extraction.

Adhering to these guidelines fosters informed decisions regarding resource utilization, promoting sustainability and mitigating environmental consequences.

The subsequent sections will discuss the application of these principles in specific contexts and industries.

1. Sustainability

Sustainability, in the context of naturally replenished assets, refers to the practice of utilizing resources in a manner that meets current needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own. This principle is intrinsically linked to renewable resource management and energy policies.

- Environmental Preservation

Preserving environmental integrity is a cornerstone of sustainability. Unsustainable extraction or utilization can degrade ecosystems, diminishing the long-term availability of the resource itself. For instance, clear-cutting forests for biomass fuel can lead to soil erosion, habitat loss, and reduced carbon sequestration, negating the benefits of utilizing an otherwise replenishable resource. Proper forest management practices, such as selective logging and reforestation, mitigate these adverse effects.

- Economic Viability

Sustainable resource use also necessitates economic viability. Projects reliant on sources of energy must be economically competitive to ensure long-term adoption and scalability. Government incentives, technological innovation, and streamlined regulatory processes can promote economic viability, making them more attractive to investors and consumers. This involves assessing the life cycle costs, including initial investment, operational expenses, and potential environmental liabilities.

- Social Equity

The transition to greater usage must address social equity, ensuring fair access to resources and benefits. Resource development projects should not disproportionately burden marginalized communities or exacerbate existing inequalities. For instance, large-scale hydropower projects can displace indigenous populations and disrupt traditional livelihoods. Stakeholder engagement and community benefit agreements are essential for promoting social equity and ensuring that renewable resource projects contribute to broader societal well-being.

- Resource Efficiency

Maximizing resource efficiency is fundamental to sustainable practices. Minimizing waste, optimizing energy consumption, and promoting circular economy principles are crucial for reducing the overall environmental footprint. This encompasses not only the extraction and utilization phases but also the manufacturing, transportation, and disposal of related technologies, such as solar panels and wind turbines. Life cycle assessments can identify opportunities for improving resource efficiency across the entire supply chain.

Collectively, these facets of sustainability underscore the importance of a holistic approach to resource management. A focus solely on replenishable aspects, without considering the broader environmental, economic, and social implications, can undermine long-term sustainability goals. Sustainable practices entail a commitment to responsible resource utilization, equitable access, and continuous improvement in resource efficiency.

2. Replenishment Rate

The replenishment rate is a critical determinant in categorizing a resource as sustainable. A resource is considered renewable if its rate of natural regeneration equals or exceeds the rate of its consumption. An imbalance favoring consumption over regeneration ultimately leads to resource depletion, negating its long-term sustainability. Solar energy exemplifies a resource with a practically limitless replenishment rate, as solar radiation is continuously emitted by the sun. Conversely, groundwater, although naturally replenished, can be rendered non-renewable if extraction rates consistently surpass the aquifer’s recharge rate, leading to water scarcity.

The significance of the replenishment rate is particularly evident in the management of biomass resources. Forests, for instance, possess the potential for sustainable yield if harvesting practices are aligned with the forest’s growth rate. However, deforestation driven by unsustainable logging or agricultural expansion can severely diminish the forest’s capacity to regenerate, transforming a potentially renewable resource into a non-renewable one. Similarly, fisheries management relies heavily on understanding the reproductive rate and population dynamics of fish stocks to prevent overfishing and ensure the long-term viability of the fishing industry. Accurate assessment of replenishment rates requires ongoing monitoring, scientific modeling, and adaptive management strategies that respond to changing environmental conditions.

In conclusion, the replenishment rate serves as a fundamental metric for evaluating the sustainability of any resource. A comprehensive understanding of this rate, coupled with responsible management practices, is essential for ensuring the long-term availability of resources and mitigating the environmental consequences of resource depletion. Challenges persist in accurately quantifying replenishment rates, particularly for complex ecosystems. Sustainable solutions require continuous refinement of data collection methodologies, collaborative governance structures, and a commitment to conservation principles.

3. Environmental Impact

Environmental impact is a pivotal consideration when evaluating the sustainability of any resource. While often perceived as inherently benign, even replenishable sources can exert significant environmental consequences depending on their extraction, processing, and utilization methods. A thorough understanding of these impacts is essential for informed decision-making regarding energy policy and resource management.

- Land Use

The physical footprint of renewable energy infrastructure can result in habitat loss, fragmentation, and alteration of ecosystems. Large-scale solar farms and wind turbine installations require substantial land areas, potentially displacing agricultural activities or impacting sensitive ecological zones. Hydropower dams can inundate vast tracts of land, disrupting riverine ecosystems and affecting local biodiversity. Careful site selection, mitigation strategies, and responsible land management practices are crucial for minimizing the land use impacts. Examples include offshore wind farms, which reduce land-based footprint, and co-location of solar arrays with agricultural activities (agrivoltaics).

- Resource Consumption

The manufacturing and deployment of renewable energy technologies often necessitate the consumption of finite resources, including critical minerals and rare earth elements. Solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries rely on materials such as lithium, cobalt, and neodymium, the extraction of which can have significant environmental and social impacts. Sustainable sourcing practices, material efficiency improvements, and recycling initiatives are essential for reducing the resource consumption associated with renewable energy deployment. Life cycle assessments provide a framework for quantifying the resource intensity of different energy technologies.

- Pollution

Certain replenishable energy technologies can generate pollution during their operational or manufacturing phases. Biomass combustion, for example, can release particulate matter and other air pollutants, contributing to respiratory problems and environmental degradation. Hydropower dams can alter water quality and flow regimes, affecting aquatic ecosystems and downstream users. Proper emission controls, advanced combustion technologies, and environmentally sensitive dam management practices are necessary to minimize pollution impacts. The use of closed-loop geothermal systems can minimize the risk of groundwater contamination.

- Wildlife Impacts

Renewable energy infrastructure can pose risks to wildlife, particularly birds and bats. Wind turbines can cause avian and bat mortality through collisions, while solar farms can attract insects and birds, leading to mortality from exposure to concentrated sunlight. Hydropower dams can impede fish migration and alter aquatic habitats. Mitigation measures such as turbine placement, operational curtailment during peak migration periods, and fish passage structures can reduce wildlife impacts. Comprehensive environmental impact assessments are essential for identifying potential wildlife risks and implementing appropriate mitigation strategies.

In conclusion, while providing a sustainable energy alternative, implementation has environmental impacts. Careful planning, technology improvements and lifecycle assessments are necessary to ensure minimal and sustainable implementation and management.

4. Energy Balance

Energy balance, in the context of sustainable resources, refers to the ratio of energy output from a given resource to the energy input required to extract, process, and deliver that energy. A positive energy balance, where the energy output significantly exceeds the energy input, is a fundamental characteristic of viable sustainable resources. If the energy balance is negative or close to zero, the resource may not be a practically viable alternative to conventional energy sources, regardless of its replenishable nature. For instance, while biomass is technically a sustainable resource, the energy required for cultivation, harvesting, transportation, and conversion into usable energy can substantially reduce its net energy output, impacting its overall sustainability. Conversely, solar energy often exhibits a high energy balance, as the energy input for manufacturing and installing solar panels is typically recouped within a few years of operation, with decades of continued energy generation.

The significance of energy balance extends to the economic and environmental implications of sustainable resource utilization. A higher energy balance translates into lower operational costs, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and increased resource efficiency. For example, geothermal energy, which harnesses heat from the earth’s interior, can provide a stable base load power supply with a relatively high energy balance, as the heat source is continuously replenished. Similarly, hydropower, which utilizes the potential energy of water, can achieve a high energy balance in locations with abundant rainfall and suitable topography. However, the construction of large-scale hydropower dams can have significant environmental consequences, highlighting the need for a comprehensive assessment that considers both the energy balance and the broader environmental impacts.

In conclusion, energy balance is a critical metric for evaluating the practicality and sustainability of various resources. Achieving a positive and substantial energy balance is essential for ensuring that sustainable resources can effectively contribute to meeting global energy demands while minimizing environmental impacts. Technological advancements aimed at improving the energy balance of less efficient technologies are essential for realizing a sustainable energy future. This analysis also contributes to more informed policy decisions regarding investments in different renewable resource technologies.

5. Resource Origin

The origin of a resource is a primary determinant in its classification as renewable or non-renewable. Understanding the genesis of a resource elucidates its potential for natural replenishment and, consequently, its long-term availability.

- Solar Radiation

Solar radiation originates from nuclear fusion reactions within the sun. This process emits a continuous stream of energy, making solar energy virtually inexhaustible on a human timescale. Harnessing solar energy via photovoltaic cells or concentrated solar power systems represents a direct utilization of a resource with an astronomical origin and inherent renewability.

- Wind Patterns

Wind is generated by differential heating of the Earth’s surface by solar radiation. This uneven heating creates pressure gradients, driving air movement and establishing wind patterns. Consequently, wind energy, captured by wind turbines, is indirectly derived from solar energy. The continuous nature of solar input ensures the ongoing creation of wind, classifying it as a renewable resource.

- Geothermal Heat

Geothermal energy stems from two primary sources: primordial heat from the Earth’s formation and radioactive decay of materials in the Earth’s interior. This heat continuously flows towards the surface, creating geothermal gradients that can be tapped for electricity generation or direct heating applications. The Earth’s internal heat represents a vast and continuously replenishing reservoir, rendering geothermal energy a sustainable resource, although localized depletion can occur if extraction rates are not carefully managed.

- Hydrological Cycle

The hydrological cycle, driven by solar energy, involves evaporation, condensation, precipitation, and runoff, continuously replenishing freshwater resources. Hydropower, which utilizes the potential energy of water flowing from higher to lower elevations, is thus indirectly reliant on solar energy. Sustainable hydropower development requires careful management of water resources to balance energy generation with environmental considerations, such as maintaining river flows and protecting aquatic ecosystems.

The origin of each resource, whether directly or indirectly linked to ongoing natural processes like solar radiation, geothermal activity, or the hydrological cycle, fundamentally dictates its renewability. Identifying and understanding these origins is crucial for developing sustainable energy strategies and mitigating reliance on finite resources.

6. Long-Term Availability

Long-term availability is a cornerstone characteristic for categorizing a resource as replenishable. A resource may exhibit a degree of renewability, but its classification as a sustainable alternative hinges on its capacity to provide a consistent supply over extended periods. For example, while forest biomass regrows after harvesting, unsustainable logging practices can diminish the forest’s ability to regenerate, jeopardizing its long-term availability as a reliable energy source. Similarly, geothermal resources, dependent on underground reservoirs of hot water or steam, can face depletion if extraction rates surpass the reservoir’s recharge capacity. Therefore, merely being ‘renewable’ is insufficient; consistent replenishment ensuring ongoing utility is paramount.

Hydropower demonstrates the interplay between renewability and long-term availability. While the water cycle continuously replenishes rivers, climate change-induced droughts can significantly reduce river flows, impacting hydropower generation. Consequently, the long-term availability of hydropower depends not only on the inherent renewability of water but also on climate stability and responsible water management practices. Furthermore, technological advancements play a vital role; improved solar panel efficiency, for instance, can enhance the overall energy output from sunlight, increasing its long-term availability by maximizing energy harvest from the existing source. The challenge lies in not only utilizing sustainable resources but also investing in technologies and practices that secure their ongoing usability.

In summary, long-term availability serves as a crucial lens through which to evaluate replenishable resources. Resources possessing the inherent capacity to regenerate are not truly sustainable unless their use is managed in a way that ensures they will remain accessible for future generations. This requires a holistic approach encompassing responsible resource management, climate change mitigation, and ongoing technological innovation. Without this long-term perspective, the promise of resource sustainability remains unfulfilled.

7. Technological Advancements

Technological advancements significantly impact the viability and efficiency of different replenishable energy sources. Improvements in energy conversion, storage, and distribution directly influence the economic feasibility and environmental performance of these resources. For instance, the evolution of photovoltaic (PV) cell technology has substantially increased the efficiency of solar energy capture, reducing the land area required for solar farms and lowering the cost per kilowatt-hour generated. Similarly, advancements in wind turbine design, including taller towers and larger rotor diameters, have enabled the harnessing of stronger and more consistent wind resources, enhancing the power output and reliability of wind energy. These improvements in core technologies are paramount to the scalability and widespread adoption of replenishable energy sources.

Energy storage technologies, such as lithium-ion batteries and pumped hydro storage, play a crucial role in addressing the intermittency challenges associated with solar and wind power. Advanced battery management systems and grid integration technologies enable the seamless integration of variable renewable energy sources into the existing electrical grid, ensuring a stable and reliable power supply. Moreover, advancements in smart grid technologies, including real-time monitoring and control systems, optimize the distribution of sustainable energy, enhancing grid resilience and reducing transmission losses. Furthermore, improvements in materials science and manufacturing processes contribute to the durability and longevity of these technologies, lowering life-cycle costs and minimizing environmental impacts. For example, the development of more durable and recyclable wind turbine blades reduces the environmental footprint of wind energy and extends the operational lifespan of wind farms.

In conclusion, technological innovation is a critical catalyst for unlocking the full potential of sustainable resources. Continuous investment in research and development, coupled with supportive policy frameworks, is essential for driving further technological advancements and accelerating the transition to a sustainable energy future. The interconnectedness of technological progress and energy accessibility underscores the importance of prioritizing innovation as a strategic imperative. Realizing the potential of replenishable resources relies heavily on continued developments and breakthroughs in associated technologies.

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding Replenishable Resources

This section addresses common inquiries about identifying and understanding resources with the capacity for natural regeneration.

Question 1: What fundamentally distinguishes a replenishable resource from a finite one?

A key distinction lies in the regeneration rate. A replenishable resource naturally replenishes itself at a rate comparable to or exceeding its consumption rate, whereas a finite resource exists in limited quantities and is depleted by usage.

Question 2: Is biomass always considered a replenishable resource?

While biomass originates from recently living organic matter and has the ability to regrow, its sustainability depends on management practices. Unsustainable harvesting, like deforestation, can negate its renewability by depleting resources faster than they can replenish.

Question 3: How does technological advancement affect resource classification?

Technology can improve the efficiency of resource utilization and expand access to previously unusable assets. Enhanced drilling techniques, for instance, extend the reach of geothermal extraction, making more heat accessible. Efficient solar panels can increase the long-term availability by maximizing energy harvest from the existing source.

Question 4: Does the geographical location impact the renewability of a resource?

Location significantly influences resource viability. Regions with consistent sunlight are better suited for solar energy, while areas with steady wind patterns favor wind energy generation. Location also impacts biomass sustainability due to varying growth conditions and agricultural practices.

Question 5: Are there environmental trade-offs associated with the utilization of seemingly benign resources?

Indeed. Hydropower, despite its clean energy generation, can disrupt river ecosystems and alter water flow patterns. Solar panel manufacturing involves rare earth minerals, extraction that entails environmental consequences. A holistic approach is required, considering the entire life cycle impact.

Question 6: How is the long-term availability of water categorized in the context of climate change?

Climate change can significantly affect precipitation patterns and water availability. While water itself is a naturally replenished resource, altered weather conditions can disrupt the hydrological cycle, reducing the reliability of water sources in many regions and impacting both human and ecological needs.

Understanding the dynamics between extraction, replenishment, and environmental impact is paramount for ensuring the responsible utilization of these resources. A thorough analysis enables informed decision-making regarding energy policy and consumption habits.

The subsequent discussion turns to practical applications and implications in various sectors.

Determining Replenishable Resource Options

The preceding analysis has illuminated the multifaceted considerations essential for discerning naturally replenished assets. The identification process transcends simplistic categorization, demanding a comprehensive evaluation of replenishment rates, environmental impacts, energy balances, resource origins, long-term availabilities, and the influence of technological advancements. A truly replenishable resource not only regenerates naturally but also offers a sustainable pathway to meet energy and material needs without compromising the well-being of future generations.

Effective decision-making regarding resource utilization necessitates a commitment to continuous monitoring, adaptive management, and technological innovation. Prioritizing strategies that minimize environmental harm, optimize resource efficiency, and promote equitable access is crucial for transitioning towards a sustainable future. Furthermore, robust policy frameworks and collaborative governance structures are essential for fostering responsible resource management and incentivizing the adoption of technologies that enhance the long-term viability of sustainable alternatives. Understanding the nuanced characteristics and trade-offs associated with replenishable resources is not merely an academic exercise but a prerequisite for securing a resilient and equitable future for all.