Systems and materials that provide the ability to do work, generate heat, or emit light are crucial for societal function. These encompass a wide array of forms, from fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas to renewable alternatives like solar, wind, and geothermal power. Each possesses distinct characteristics regarding availability, environmental impact, and technological requirements for harnessing its potential.

The availability of functional power mechanisms is foundational to modern civilization. They enable industrial production, transportation, heating, cooling, and the operation of electrical devices. Historically, the development and utilization of different mechanisms have profoundly influenced economic growth, technological advancement, and geopolitical dynamics. A reliable and diverse portfolio is essential for sustained prosperity and resilience against disruptions.

The subsequent sections will delve into specific classifications based on renewability, examining the characteristics, advantages, and challenges associated with each category. Furthermore, the article will explore the impact of each on the environment and discuss the future directions of development and innovation within the industry.

Optimizing Resource Selection and Utilization

Effective management and strategic selection are vital for ensuring long-term stability and minimizing adverse consequences. Understanding the characteristics and trade-offs associated with each mechanism is crucial for making informed decisions.

Tip 1: Diversify the Portfolio: Reliance on a single category can create vulnerabilities. A mixed portfolio reduces risks associated with price fluctuations, resource depletion, and technological disruptions. For example, combining solar and wind with natural gas provides a more stable and adaptable structure.

Tip 2: Prioritize Efficiency: Implementing measures to improve energy efficiency across all sectors reduces overall demand and lowers consumption. This includes investments in energy-efficient appliances, building insulation, and industrial processes.

Tip 3: Evaluate Life Cycle Costs: Consider the full life cycle cost, including initial investment, operational expenses, maintenance, and decommissioning. While some appear inexpensive upfront, long-term costs, including environmental remediation, can be substantial.

Tip 4: Invest in Research and Development: Continuous investment in R&D is essential for developing and deploying innovative solutions. This includes advanced battery storage, carbon capture technologies, and more efficient generation processes.

Tip 5: Support Sustainable Practices: Promote policies and practices that support environmentally responsible mechanisms. This includes carbon pricing, regulations on emissions, and incentives for renewable investment.

Tip 6: Assess Grid Infrastructure: The ability to transmit and distribute power efficiently is critical. Investing in grid modernization and smart grid technologies is essential for integrating renewable options and improving reliability.

Tip 7: Promote Public Awareness: Educating the public about the importance of conscious resource management can drive behavioral changes and support policy initiatives. This can involve campaigns promoting energy conservation and the adoption of efficient technologies.

Strategic adoption requires a holistic perspective, encompassing economic, environmental, and social considerations. By prioritizing efficiency, diversifying portfolios, and supporting innovation, a more secure and sustainable future can be achieved.

The following sections will explore specific applications in various sectors and discuss emerging trends shaping the future landscape.

1. Renewability

Renewability, within the context of usable power, denotes the ability of a resource to be replenished at a rate equal to or exceeding its rate of consumption. This characteristic is fundamental to long-term sustainability. Power mechanisms categorized as renewable offer a pathway to mitigate resource depletion and reduce reliance on finite reserves. Solar irradiance, for instance, exemplifies a renewable mechanism; the sun’s energy continuously reaches the Earth, providing a consistent and virtually inexhaustible input for electricity generation via photovoltaic systems. Similarly, wind, driven by solar-induced atmospheric pressure gradients, provides a perpetual supply for wind turbines. This contrasts with fossil fuels, which are formed over millions of years and cannot be replenished on a human timescale.

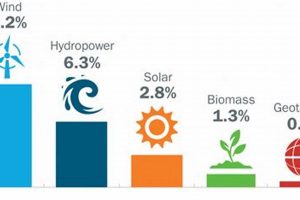

The significance of renewability extends beyond resource conservation. Its adoption has profound implications for reducing environmental impact. The combustion of fossil fuels releases greenhouse gasses, contributing to climate change and associated consequences. Renewable power mechanisms, such as solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal, generally produce significantly lower or zero greenhouse gas emissions during operation. The incorporation of hydroelectric power generation systems, harnessing the kinetic energy of flowing water, into electrical grids exemplifies the practical application of renewability and carbon footprint reduction. Increased reliance on such mechanisms decreases the demand for fossil fuel-based generation, mitigating the release of harmful emissions and promoting cleaner air and water.

However, the transition to renewable power mechanisms presents challenges. Intermittency, the variability of solar and wind resources, necessitates the development of energy storage solutions, such as battery systems or pumped hydro storage, to ensure grid stability. Furthermore, the initial capital investment for renewable energy infrastructure can be substantial, requiring supportive policies and financial mechanisms to encourage widespread adoption. Despite these challenges, the long-term benefits of prioritizing renewability, including resource security, environmental protection, and economic diversification, underscore its critical role in shaping a sustainable power future.

2. Availability

The term “Availability” in the context of usable power signifies the degree to which a particular mechanism can be accessed and utilized within a specific geographical location or timeframe. It is a multifaceted concept encompassing geographical distribution, infrastructure requirements, technological accessibility, and regulatory frameworks. Understanding the nuances of availability is crucial for energy planning, infrastructure development, and ensuring a stable and secure supply.

- Geographical Distribution

The geographical distribution of a certain power mechanism is a primary determinant of its availability. For example, geothermal power is predominantly available in regions with high geothermal activity, such as Iceland or the western United States. Similarly, hydroelectric power requires suitable river systems and topography for dam construction. The uneven distribution across the globe necessitates strategic planning to leverage regional advantages and compensate for limitations in other areas.

- Infrastructure Requirements

Infrastructure development is inextricably linked to availability. Even if a resource is abundant, its utilization is constrained by the presence of adequate infrastructure for extraction, processing, transportation, and distribution. The extraction of offshore natural gas necessitates pipelines and processing facilities, while the integration of wind power requires transmission lines to connect remote wind farms to urban centers. Investments in infrastructure are therefore paramount to increasing the practical availability.

- Technological Accessibility

Technological accessibility refers to the level of technological development required to harness and convert energy into usable forms. While solar irradiance is globally abundant, its utilization requires photovoltaic technology, which has varying levels of accessibility depending on technological advancements and manufacturing capabilities. Similarly, advanced nuclear fission technologies or fusion energy remain less available due to their complexity and development stage.

- Regulatory Frameworks

Regulatory frameworks, including permitting processes, environmental regulations, and incentives, significantly influence the availability. Streamlined permitting can expedite the deployment of renewable energy projects, while stringent environmental regulations can restrict the exploitation of certain resources. Government policies promoting or hindering the accessibility shape the energy landscape. Supportive regulatory environments facilitate investment and accelerate the integration of these mechanisms.

In conclusion, the availability is a key determinant of the usability of a variety of power mechanisms. Recognizing its multifaceted nature, which encompasses geographical limitations, infrastructural requirements, technological constraints, and regulatory obstacles, is essential for making well-informed strategic choices that guarantee dependable usable energy and promote environmentally responsible practices.

3. Efficiency

Efficiency, in the context of usable power, quantifies the proportion of input energy converted into useful output. This metric is critical when assessing the viability and sustainability of different power mechanisms. Higher efficiency translates to reduced resource consumption for a given energy output, mitigating environmental impact and lowering operational costs. For example, a modern combined cycle gas turbine power plant can achieve efficiencies exceeding 60%, while older coal-fired plants may operate at efficiencies closer to 35%. This difference illustrates the significant impact of technological advancements on resource utilization.

The efficiency directly influences the overall cost-effectiveness of any given mechanism. Lower operating expenses are often associated with more efficient systems due to reduced fuel or resource consumption. Furthermore, increased efficiency reduces the strain on existing infrastructure. Consider electric vehicles: compared to internal combustion engines, they exhibit substantially higher efficiency from source to wheel. This reduces the demand for electricity from the grid for the same distance traveled, mitigating the need for extensive grid upgrades. In the same way, more energy-efficient buildings require smaller heating and cooling systems, decreasing overall energy demand and lowering utility bills for occupants.

Ultimately, improved efficiency is a key driver of technological innovation within the usable energy landscape. Research and development efforts continually aim to improve the energy conversion rates of solar panels, wind turbines, and energy storage systems. Pursuing better mechanisms promotes greater competitiveness and helps to meet growing energy demands while minimizing resource depletion and environmental degradation. Therefore, focusing on and prioritizing mechanisms with better conversion rates is not just an economical choice but also a vital element for a sustainable energy future.

4. Environmental Impact

The selection and utilization of usable mechanisms exert a profound and multifaceted impact on the environment. These effects span from direct alterations to ecosystems to broader implications for climate stability and human health. A comprehensive understanding of these consequences is essential for informed decision-making and the development of sustainable strategies.

- Air Quality Degradation

The combustion of fossil fuels releases particulate matter, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and other pollutants into the atmosphere, contributing to respiratory illnesses, acid rain, and smog. Coal-fired power plants are particularly significant contributors to air pollution. Shifting towards cleaner alternatives can substantially improve air quality and mitigate associated health risks.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Change

The release of greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide, from fossil fuel combustion is a primary driver of climate change. Rising global temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events are among the projected consequences. Transitioning to zero-emission mechanisms is crucial for stabilizing the climate and mitigating these risks.

- Habitat Destruction and Biodiversity Loss

Extraction, processing, and transportation can lead to habitat destruction and biodiversity loss. Coal mining, for instance, often involves deforestation and the alteration of landscapes. Hydroelectric dams can disrupt river ecosystems and impact fish migration. Mitigating these impacts requires careful planning, environmental assessments, and the implementation of conservation measures.

- Water Resource Depletion and Pollution

Many require significant amounts of water for cooling or processing. Water extraction can deplete aquifers and reduce river flows, impacting aquatic ecosystems and water availability for other uses. Additionally, mining and industrial processes can release pollutants into water bodies, contaminating water supplies and harming aquatic life.

These interrelated environmental consequences underscore the need for a holistic approach to energy planning. By considering the full life cycle impact of different mechanisms, from extraction to disposal, societies can make informed decisions that prioritize environmental sustainability and minimize adverse effects on ecosystems and human health.

5. Cost-Effectiveness

The economic viability of various mechanisms is a central consideration in energy planning and policy. The ability to deliver power at a competitive price point influences adoption rates, investment decisions, and the overall sustainability of the grid. It requires a thorough analysis of capital expenditures, operational costs, fuel expenses, and potential revenue streams.

- Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE)

The LCOE is a metric used to compare the total cost of power generation across different mechanisms over their lifespan. It incorporates capital expenditures, fuel costs, operational expenses, and financing costs, discounted to present value. Technologies with a lower LCOE are generally more economically competitive, influencing investment decisions and energy mix strategies. Solar and wind power have seen significant LCOE reductions in recent years, making them increasingly competitive with traditional fossil fuels.

- Capital Expenditures (CAPEX)

CAPEX represents the upfront investment required to build a power plant or establish extraction infrastructure. Mechanisms with high CAPEX, such as nuclear power plants or offshore wind farms, require substantial initial investment, potentially deterring development. Conversely, mechanisms with lower CAPEX, like natural gas-fired power plants or distributed solar installations, offer a more accessible entry point for investors.

- Operational Expenditures (OPEX)

OPEX encompasses the ongoing costs associated with operating and maintaining a power generating facility. This includes fuel costs, labor expenses, maintenance and repair costs, and regulatory compliance fees. Mechanisms that rely on free or low-cost mechanisms, such as solar and wind, typically have lower OPEX than fossil fuel-based power plants, which are subject to fuel price volatility.

- Externalities and Social Costs

Traditional economic analyses often fail to account for externalities, such as air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and health impacts. Incorporating social costs into the analysis provides a more comprehensive assessment of the true cost. Carbon pricing mechanisms, such as carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems, can internalize these externalities, making more environmentally friendly mechanisms more economically competitive.

The interplay between these facets ultimately determines the economic competitiveness of different usable power options. As technology advances and regulatory environments evolve, the dynamics of cost-effectiveness are constantly shifting, requiring ongoing analysis and adaptation in energy planning and investment strategies. For instance, advancements in battery storage are improving the economic viability of intermittent renewables, while carbon capture technologies could potentially extend the lifespan of fossil fuel-based generation.

6. Technological Feasibility

Technological feasibility, in the context of usable power, fundamentally defines the practical limits of harnessing and deploying particular mechanisms. It serves as a gatekeeper, determining which resources are accessible with current engineering capabilities and which remain theoretical or economically prohibitive. The evolution of power generation is inextricably linked to advancements in technology, from the initial harnessing of coal for steam power to the modern development of advanced nuclear reactors and grid-scale energy storage systems. Without the necessary technological infrastructure and expertise, abundant resources remain untapped or underutilized.

The development of photovoltaic cells exemplifies the effect of technological advancement. Early solar cells were inefficient and costly, limiting their deployment to niche applications. However, continuous research and development have led to significant improvements in cell efficiency, manufacturing processes, and material science, drastically reducing the cost of solar power and enabling its widespread adoption. Similarly, the feasibility of geothermal power is contingent on the development of enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) capable of accessing geothermal resources in areas lacking natural hydrothermal reservoirs. EGS technologies involve creating artificial fractures in hot, dry rocks to allow water circulation and heat extraction. The ongoing development and refinement of EGS technology will significantly expand the geographic availability of usable geothermal power.

Ultimately, the realization of a sustainable and diverse usable landscape hinges on continuous innovation and technological progress. Overcoming existing technological barriers, such as improving the efficiency of energy storage systems, developing cost-effective carbon capture technologies, and enhancing the reliability of renewable generation, is crucial for meeting future demands while minimizing environmental impacts. The pursuit of these advancements requires sustained investment in research and development, collaborative partnerships between industry and academia, and supportive policy frameworks that incentivize innovation and deployment.

Frequently Asked Questions on Usable Power Mechanisms

This section addresses common queries and misconceptions regarding the mechanisms to power systems and infrastructures.

Question 1: What is meant by “renewable” in the context of usable resources?

Renewable refers to mechanisms that are naturally replenished at a rate comparable to or faster than their rate of consumption. Examples include solar radiation, wind, flowing water, and geothermal heat. These resources are considered sustainable over long periods due to their capacity for regeneration.

Question 2: Why is it important to diversify a society’s portfolio of mechanisms?

Diversification minimizes risk associated with resource depletion, price volatility, and technological obsolescence. A varied portfolio can enhance security and resilience against disruptions in any single mechanism.

Question 3: How does the “Levelized Cost of Energy” (LCOE) factor into mechanism selection?

The LCOE provides a standardized metric for comparing the total cost of power generation from different mechanisms over their lifespan, including capital expenditures, operational expenses, and fuel costs. Lower LCOE values typically indicate more economically competitive options.

Question 4: What are the main environmental concerns associated with the use of fossil fuels?

The combustion of fossil fuels releases greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change. Additionally, it generates air pollutants that can cause respiratory illnesses and acid rain. Extraction processes can also disrupt ecosystems and contaminate water supplies.

Question 5: How does mechanism “availability” affect energy planning?

Availability refers to the accessibility and geographical distribution of mechanisms. Planning must consider factors like climate, geography, and infrastructure requirements to effectively harness available resources.

Question 6: What role does technology play in enhancing the feasibility of using alternative resources?

Technological innovation is vital for improving the efficiency, reducing the cost, and expanding the geographic availability of alternative mechanisms. Advances in areas such as photovoltaic cells, energy storage, and geothermal extraction can significantly enhance the viability of these mechanisms.

In summary, the choices regarding usable sources depend on multiple variables. Effective and informed energy strategy, in addition to long-term sustainability, may be achieved through comprehending renewability, diversifying energy holdings, and minimizing ecological footprints.

The ensuing sections will explore specific applications and potential challenges in various sectors.

Conclusion

This exploration of sources of energy has illuminated the complexities inherent in meeting societal demands while striving for sustainability. The assessment of renewability, availability, efficiency, environmental impact, cost-effectiveness, and technological feasibility reveals the trade-offs associated with each mechanism. Informed decision-making requires a comprehensive understanding of these factors and a commitment to continuous innovation.

The ongoing transition toward a more sustainable structure necessitates sustained investment in research and development, supportive policy frameworks, and a global commitment to minimizing environmental impact. The future hinges on the responsible and strategic utilization of available mechanisms, ensuring access for future generations while safeguarding the planet’s resources. The decisions made today will define the energy landscape of tomorrow.

![Biogas: Is It a Renewable Source of Energy? [Answered] Renewable Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future | Clean & Green Power Biogas: Is It a Renewable Source of Energy? [Answered] | Renewable Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future | Clean & Green Power](https://pplrenewableenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/th-204-300x200.jpg)