These finite natural materials exist in limited quantities on Earth and cannot be replenished at a rate comparable to their consumption. Examples include fossil fuels like coal, oil, and natural gas, as well as nuclear fuels such as uranium. Once depleted, their formation requires geological timescales, rendering them effectively unavailable for human use within a reasonable timeframe.

Their utilization has historically driven industrial development and provided substantial energy and material resources. However, reliance on these sources presents significant environmental and economic challenges. Extraction and combustion processes contribute to air and water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and habitat destruction. Furthermore, the eventual depletion of these reserves necessitates the development and adoption of alternative sustainable solutions.

The subsequent sections will delve into the environmental impact, economic considerations, and potential renewable energy alternatives associated with the continued dependence on these limited and exhaustible resources.

Mitigating the Impact of Exhaustible Resources

Effective strategies are crucial for managing the challenges presented by materials which are not renewable. The following guidelines outline key actions to minimize environmental and economic repercussions associated with their extraction and utilization.

Tip 1: Prioritize Energy Efficiency: Implementing energy-efficient technologies across all sectors, from residential buildings to industrial processes, reduces overall demand. Examples include using LED lighting, improving insulation, and optimizing industrial machinery.

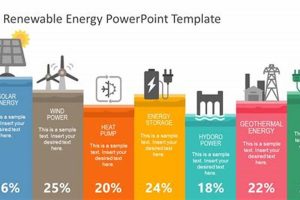

Tip 2: Invest in Renewable Energy Infrastructure: Transitioning to sustainable energy sources such as solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal power decreases reliance on these finite materials. Government incentives and private sector investments are vital for this transition.

Tip 3: Promote Resource Conservation: Encouraging responsible consumption and reducing waste generation through recycling programs, reuse initiatives, and minimizing packaging minimizes the extraction of raw materials.

Tip 4: Develop Advanced Recycling Technologies: Investing in research and development of more efficient and effective recycling processes allows for the recovery and reuse of valuable materials, extending their lifespan.

Tip 5: Implement Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) Technologies: Deploying CCS technologies at power plants and industrial facilities can mitigate the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, addressing climate change concerns.

Tip 6: Stricter Environmental Regulations: Governments must implement and enforce stringent environmental regulations governing the extraction, processing, and transportation of these materials to minimize pollution and habitat destruction.

Tip 7: Promote Public Awareness and Education: Educating the public about the environmental and economic consequences of reliance on such resources fosters responsible consumption habits and supports the adoption of sustainable alternatives.

Adopting these practices reduces environmental degradation, mitigates resource scarcity, and fosters a more sustainable future. Diversifying energy sources and embracing resource efficiency are crucial steps for long-term economic stability and environmental protection.

The subsequent sections will further examine the specific renewable energy alternatives and policy interventions required for a comprehensive shift away from dependence on these finite resources.

1. Finite Supply

The concept of finite supply forms the bedrock of understanding materials that cannot be replenished at a rate commensurate with their consumption. This inherent limitation dictates the environmental, economic, and geopolitical ramifications associated with their utilization. The following elements detail the implications of this constraint.

- Fixed Quantity

Materials that cannot be renewed exist in a fixed total quantity on Earth. This quantity, established through geological processes over vast timescales, represents the absolute upper limit of availability. Extraction continuously reduces this total, without a natural mechanism for significant regeneration. The initial supply is all that will ever be available.

- Depletion Threshold

As extraction proceeds, the accessible supply diminishes, eventually reaching a point where further retrieval becomes economically unviable or physically impossible. This threshold is not a fixed point but rather a range influenced by technological advancements and economic factors. Nevertheless, the underlying principle remains: continued consumption inevitably leads to depletion.

- Resource Scarcity

Diminishing reserves coupled with increasing demand for materials that cannot be renewed generates resource scarcity. This scarcity drives up prices, potentially impacting economic stability and international relations. Access to these diminishing reserves becomes a strategic imperative, leading to potential conflicts and market distortions.

- Strategic Reserves

Nations and corporations maintain strategic reserves to buffer against supply disruptions and price volatility. These reserves, however, only provide temporary relief and do not fundamentally alter the finite nature of the resources. The existence of reserves, while essential for short-term stability, highlights the long-term challenge posed by limited availability.

These facets underscore the inescapable reality that materials which cannot be renewed are subject to eventual exhaustion. Acknowledging this fundamental limitation is essential for the development and implementation of sustainable alternatives, and for mitigating the consequences of increasing scarcity.

2. Fossil Fuels

Fossil fuels are a quintessential example of materials that cannot be replenished at a rate comparable to their consumption. Formed over millions of years from the remains of ancient organisms, they represent a finite store of energy. Their role as a primary energy source for industrial societies is undeniable, powering transportation, electricity generation, and industrial processes. The combustion of these fuels releases stored carbon into the atmosphere, contributing significantly to climate change. This causal link underscores a critical environmental challenge posed by their widespread use. For instance, global reliance on coal for electricity has led to increased atmospheric carbon dioxide, intensifying the greenhouse effect.

The importance of fossil fuels within the category of materials that cannot be renewed lies in their historical ubiquity and ongoing dependence. For example, crude oil powers the majority of the world’s transportation sector. Transitioning away from fossil fuels necessitates the development and deployment of alternative energy technologies at scale, alongside changes in infrastructure and consumer behavior. Furthermore, the extraction and refinement processes associated with fossil fuels present diverse environmental risks, including oil spills, habitat destruction, and air and water pollution. These factors emphasize the need for stringent regulations and responsible resource management.

In summary, fossil fuels are a critical, yet unsustainable, component of energy production. Their extraction and combustion impact the environment and society in a way which requires careful management and forward-thinking strategy. The inherent constraint of finite reserves necessitates a paradigm shift towards alternative sustainable energy sources. This transition presents both challenges and opportunities for innovation and economic growth, requiring careful consideration of technological advancements, policy interventions, and societal adaptation.

3. Environmental Degradation

The exploitation of materials which cannot be renewed is inextricably linked to environmental degradation across various phases, from extraction to processing and final consumption. The environmental consequences stemming from the use of finite resources manifest in numerous forms, affecting ecosystems and human health. The extraction of coal, for instance, often involves mountaintop removal mining, a practice that obliterates habitats, contaminates waterways, and increases the risk of flooding. Similarly, the extraction and transportation of crude oil can lead to devastating spills, harming marine life and coastal ecosystems, as exemplified by the Deepwater Horizon disaster. These environmental repercussions are a direct consequence of the reliance on these limited resources and their associated industrial processes.

The combustion of these resources further contributes to environmental degradation through air pollution and climate change. The release of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide, traps heat in the atmosphere, leading to global warming and its associated impacts: rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and disruptions to agricultural systems. Air pollutants, such as particulate matter and sulfur dioxide, directly impact human health, contributing to respiratory illnesses and cardiovascular diseases. The burning of coal in power plants and the emissions from vehicles fueled by gasoline are primary sources of these pollutants. Furthermore, the disposal of waste products from resource extraction and processing, such as tailings from mining operations and ash from coal-fired power plants, poses significant risks to soil and water quality.

Understanding the intricate link between reliance on materials which cannot be renewed and environmental degradation is essential for formulating effective mitigation strategies. A transition to renewable energy sources, coupled with improved resource management and stricter environmental regulations, is imperative to reduce the adverse impacts on ecosystems and human well-being. The costs associated with environmental degradation, including the remediation of contaminated sites, healthcare expenses, and the economic losses from climate change impacts, underscore the need for a fundamental shift towards sustainability. Ignoring this connection perpetuates environmental damage, jeopardizing both present and future generations.

4. Economic Dependence

Economic reliance on materials which cannot be renewed constitutes a multifaceted challenge, shaping national economies, international trade dynamics, and technological innovation trajectories. This dependence exerts considerable influence over energy security, resource management strategies, and the pursuit of sustainable alternatives. Understanding the core facets of this reliance is crucial for navigating the transition towards a more sustainable economic model.

- Revenue Generation

Many nations heavily rely on the extraction and export of materials which cannot be renewed as a primary source of revenue. Oil-producing countries, for instance, generate substantial income from petroleum exports, funding government budgets, infrastructure projects, and social programs. Fluctuations in global commodity prices, driven by supply and demand dynamics, can significantly impact these economies, creating vulnerability to market volatility and potential economic instability. This dependency often inhibits diversification efforts and perpetuates reliance on the extraction sector.

- Job Creation

The exploration, extraction, processing, and transportation of such materials generate significant employment opportunities. Mining operations, oil refineries, and related industries provide jobs across various skill levels, contributing to local and national economies. However, the eventual depletion of these resources poses a long-term threat to employment prospects, necessitating the development of alternative industries and workforce retraining programs to mitigate potential job losses. The transition away from fossil fuels, for example, requires investments in renewable energy sectors to create new employment opportunities.

- Infrastructure Development

The development of infrastructure, such as pipelines, refineries, and transportation networks, is often driven by the extraction and processing of these materials. These infrastructure investments facilitate the movement of resources from extraction sites to markets, stimulating economic activity and supporting industrial development. However, the long-term viability of this infrastructure is contingent upon the continued availability of the resources and the absence of significant environmental damage. Neglecting investments in sustainable infrastructure alternatives can lock economies into dependence on non-renewable resources.

- Technological Innovation

The quest for more efficient and cost-effective methods of extracting, processing, and utilizing these materials drives technological innovation. Advanced drilling techniques, enhanced oil recovery methods, and carbon capture technologies are examples of innovations spurred by the continued reliance on materials that cannot be renewed. While these advancements may improve resource utilization efficiency, they do not fundamentally address the issue of finite supply and the need for a transition to sustainable alternatives. Innovation efforts must shift focus toward renewable energy technologies and resource conservation strategies.

These interconnected facets underscore the pervasive influence of economic dependence on materials which cannot be renewed. Addressing this dependence requires a multifaceted approach encompassing economic diversification, investments in renewable energy, technological innovation, and policy interventions that promote sustainable resource management. Failing to address this fundamental dependency risks perpetuating economic vulnerabilities and hindering the transition to a more sustainable future.

5. Geopolitical Concerns

The unequal distribution of materials that cannot be renewed across the globe, coupled with their crucial role in powering modern economies, gives rise to significant geopolitical concerns. Access to these limited resources shapes international relations, influences national security strategies, and can contribute to regional instability. The interplay between resource scarcity and political power dynamics is a defining characteristic of the 21st century.

- Resource Nationalism

Nations possessing substantial reserves may adopt policies of resource nationalism, asserting greater control over their natural resources and limiting foreign access. This can involve nationalizing resource extraction industries, imposing stricter regulations on foreign investment, or manipulating supply to influence global prices. Resource nationalism can lead to strained international relations, trade disputes, and reduced investment in resource development. Examples include disputes over oil and gas resources in the South China Sea and nationalization efforts in Latin American countries.

- Strategic Competition

Countries compete strategically to secure access to these limited materials, often through diplomatic alliances, military presence, or economic coercion. Securing access to vital energy resources, such as oil and natural gas, is a key driver of foreign policy for many nations. This competition can intensify existing geopolitical tensions and lead to proxy conflicts in resource-rich regions. The United States’ long-standing involvement in the Middle East, for instance, is partly motivated by securing access to stable oil supplies.

- Resource Curse

Resource-rich nations, paradoxically, often experience slower economic growth, higher levels of corruption, and greater political instability. This phenomenon, known as the resource curse, arises from over-reliance on resource revenues, which can distort economic development, weaken governance structures, and fuel conflict over resource control. Examples include several African nations plagued by civil wars and corruption linked to diamond and oil wealth. The lack of diversification and transparency exacerbates the negative impacts.

- Energy Security

Nations lacking domestic reserves are vulnerable to disruptions in supply and price volatility, posing a significant threat to their energy security. Dependence on foreign sources for essential materials can be exploited for political leverage, leading to diplomatic pressure or even economic sanctions. Diversifying energy sources and developing domestic renewable energy alternatives are crucial strategies for enhancing energy security and reducing geopolitical vulnerability. Germany’s shift towards renewable energy is partly driven by a desire to reduce dependence on Russian natural gas.

These interconnected facets highlight the complex geopolitical implications associated with materials which cannot be renewed. The finite nature of these resources, coupled with their uneven distribution, creates a landscape of competition, vulnerability, and potential conflict. Addressing these concerns requires a multifaceted approach encompassing international cooperation, diversification of energy sources, and a commitment to sustainable resource management. Neglecting these factors perpetuates geopolitical instability and hinders progress towards a more equitable and secure global order.

6. Depletion Rates

The rate at which materials that cannot be renewed are consumed is a critical factor in evaluating their long-term viability and sustainability. The pace of extraction and utilization dictates the lifespan of available reserves and the urgency with which alternative solutions must be developed and implemented. Understanding the forces driving depletion rates and their consequences is essential for effective resource management and energy planning.

- Exponential Consumption Growth

Global demand for energy and materials has grown exponentially over the past century, driven by population growth, industrialization, and rising standards of living. This escalating demand places immense pressure on finite resources, accelerating their depletion. For instance, the rapid expansion of developing economies like China and India has fueled a surge in coal consumption, leading to a significant reduction in global coal reserves. This trend underscores the challenge of meeting growing energy needs while simultaneously transitioning to sustainable alternatives.

- Technological Advancements

Technological innovations in extraction techniques, such as hydraulic fracturing (fracking) for oil and natural gas, can temporarily increase the availability of certain non-renewable resources. However, these advancements often come at a significant environmental cost, including water contamination and increased greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, these technological solutions only delay depletion rather than addressing the underlying issue of finite supply. Fracking, while boosting domestic energy production in some countries, also accelerates the overall depletion rate of oil and gas reserves.

- Economic Incentives

Market prices and government subsidies play a crucial role in shaping depletion rates. Low prices or subsidies can encourage wasteful consumption and discourage investment in renewable energy alternatives. Conversely, higher prices or carbon taxes can incentivize efficiency and promote the adoption of sustainable practices. The absence of carbon pricing mechanisms in many countries contributes to the artificially low cost of fossil fuels, accelerating their depletion. The presence of economic distortions affects the choices for extraction and utilization.

- Reserve Estimates and Proven Reserves

Reserve estimates, representing the total amount of a resource believed to exist, are often uncertain and subject to change based on geological surveys and technological advancements. Proven reserves, representing the portion of a resource that is economically and technically feasible to extract, provide a more accurate picture of near-term availability. However, even proven reserves are finite and subject to depletion. Misinterpretations of reserve estimates can lead to overconfidence and delayed investment in renewable alternatives. Continual re-evaluation is required as extraction proceeds and new discoveries occur.

These factors collectively influence the pace at which materials that cannot be renewed are being depleted. Recognizing these drivers and their interconnectedness is essential for developing effective policies and strategies aimed at promoting sustainable resource management and transitioning towards a more sustainable energy future. Failing to account for these influences risks accelerating depletion rates and jeopardizing long-term economic and environmental stability.

7. Energy Transition

The energy transition is intrinsically linked to the finite nature of materials which are not replenished at a rate comparable to their consumption. It represents a fundamental shift away from reliance on fossil fuels and towards sustainable energy sources, driven by environmental concerns, resource depletion, and technological advancements. The following points detail the key facets of this transition.

- Decarbonization Imperative

The primary impetus for energy transition is the need to decarbonize the global economy. Combustion of materials which cannot be renewed releases greenhouse gases, exacerbating climate change. Transitioning to renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and hydro power, reduces carbon emissions and mitigates the environmental impact. For example, the European Union’s Green Deal aims to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 through a large-scale deployment of renewable energy technologies.

- Renewable Energy Technologies

The transition requires the development, deployment, and refinement of renewable energy technologies. This includes improving the efficiency and reducing the cost of solar panels, wind turbines, and energy storage systems. Technological advancements are crucial for making renewable energy sources competitive with fossil fuels. For example, advancements in battery technology are enabling the wider adoption of electric vehicles and grid-scale energy storage.

- Infrastructure Modernization

A successful energy transition necessitates significant investments in infrastructure modernization. This involves upgrading electricity grids to accommodate distributed renewable energy generation, building new transmission lines to connect renewable energy sources to population centers, and developing charging infrastructure for electric vehicles. For example, countries are investing in smart grids to improve the reliability and efficiency of electricity distribution.

- Policy and Regulatory Frameworks

Government policies and regulatory frameworks play a critical role in accelerating the energy transition. Carbon pricing mechanisms, renewable energy mandates, and subsidies for clean energy technologies can incentivize the adoption of sustainable energy sources. Policies that promote energy efficiency and conservation also contribute to the transition. For example, many countries have implemented feed-in tariffs to encourage investment in renewable energy projects.

In conclusion, the energy transition is a complex and multifaceted process driven by the limitations of materials which cannot be renewed and the imperative to address climate change. The shift to renewable energy sources, coupled with infrastructure modernization and supportive policy frameworks, is essential for achieving a sustainable energy future and mitigating the risks associated with continued reliance on finite resources.

Frequently Asked Questions about Materials Which are Not Replenished

This section addresses common questions concerning the nature, implications, and future prospects associated with the depletion of finite natural resources.

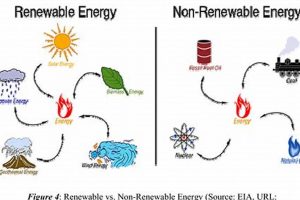

Question 1: What distinguishes materials that cannot be renewed from renewable resources?

Materials that cannot be renewed exist in finite quantities and are depleted at a rate faster than natural replenishment. Renewable resources, conversely, are naturally replenished at a rate comparable to or exceeding their consumption.

Question 2: What are the primary environmental consequences associated with materials that cannot be renewed?

Extraction, processing, and combustion frequently lead to habitat destruction, air and water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and contribute to climate change.

Question 3: How does reliance on materials that cannot be renewed impact global economies?

Economic dependence can lead to market volatility, resource scarcity, geopolitical competition, and hinder the development of sustainable alternatives.

Question 4: What are the most viable alternatives to materials that cannot be renewed?

Renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal power, along with enhanced resource efficiency and recycling initiatives, represent the most promising alternatives.

Question 5: What role do governments play in transitioning away from materials that cannot be renewed?

Governments implement carbon pricing mechanisms, renewable energy mandates, subsidies for clean energy technologies, and stricter environmental regulations.

Question 6: Is complete elimination of materials that cannot be renewed usage possible in the near future?

Complete elimination in the near future is unlikely. A gradual transition through diversification is expected as technology continues to improve.

The efficient use of materials that cannot be renewed and the implementation of sustainability methods can help mitigate and improve our environmental impact.

The following section will present case studies illustrating the implementation of sustainable practices aimed at reducing the dependence on materials that cannot be renewed.

The Imperative of Transitioning from Non-Renewable Resources

This exploration has elucidated the multifaceted challenges posed by the reliance on materials that cannot be replenished at rates comparable to their consumption. The finite nature of these resources, coupled with their environmental and geopolitical ramifications, necessitates a fundamental shift in energy production and consumption patterns. These are non-renewable resources are at the center of discussions on sustainable development and energy security. It is clear that dependence on these exhaustible supplies poses significant risks to long-term economic stability and environmental health.

Continued inaction carries profound consequences. The depletion of these supplies, alongside the escalating environmental burdens, demands immediate and decisive action. A commitment to innovation, sustainable practices, and global collaboration is crucial to ensure a resilient and equitable future. The time to act is now, to secure a sustainable path forward.