Resources that deplete over time and cannot be naturally replenished at a rate comparable to their consumption are excluded from the classification of sustainable power generators. These encompass fuels derived from geological processes occurring over millions of years. A prime illustration is the extraction and combustion of subterranean carbon deposits.

The distinction between finite and perpetual energy sources is critical for long-term environmental sustainability and energy security. Reliance on exhaustible resources carries inherent risks, including price volatility, geopolitical instability, and significant environmental consequences such as greenhouse gas emissions and habitat destruction. Historically, societies have transitioned between different energy sources, often driven by technological advancements and resource availability, but the current imperative emphasizes a shift towards sustainable options to mitigate climate change.

Understanding which power generation methods do not meet the criteria for renewability is essential for informing energy policy, investment decisions, and public awareness campaigns. This necessitates a closer examination of specific examples and the implications of their continued use.

Considerations Regarding Non-Renewable Energy Sources

This section provides guidance on identifying and understanding energy sources that are not classified as renewable. Awareness of these distinctions is crucial for making informed decisions about energy consumption and investment.

Tip 1: Identify Depletion: Recognize energy sources subject to depletion. These resources exist in finite quantities and are consumed at rates exceeding natural replenishment. Fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, exemplify this category.

Tip 2: Analyze Formation Timeframes: Evaluate the timescale required for resource formation. Energy sources requiring millions of years to form through geological processes are inherently non-renewable. This contrasts sharply with resources that regenerate within human lifespans.

Tip 3: Assess Carbon Emissions: Examine the carbon footprint associated with energy generation. Non-renewable sources often release significant amounts of greenhouse gases when combusted, contributing to climate change. This factor is a key differentiator from renewable options.

Tip 4: Consider Geopolitical Implications: Evaluate the geopolitical factors influencing resource availability and distribution. Dependence on non-renewable sources can create vulnerabilities related to resource scarcity, price volatility, and international relations.

Tip 5: Evaluate Long-Term Sustainability: Assess the long-term environmental and economic sustainability of energy choices. Prioritizing renewable alternatives mitigates the risks associated with reliance on dwindling and environmentally damaging resources.

By carefully considering these factors, individuals and organizations can make more informed decisions about energy consumption and investment, promoting a transition toward sustainable and resilient energy systems.

The following sections will explore specific examples of energy sources and their respective classifications.

1. Depletion

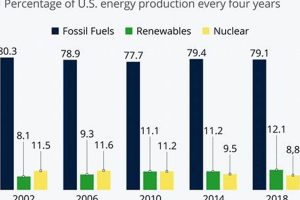

The fundamental characteristic differentiating non-renewable energy sources lies in their eventual depletion. These resources, formed over geological timescales, exist in finite quantities. Their extraction and consumption outpace natural replenishment, leading to a gradual reduction in reserves. This scarcity creates economic and geopolitical vulnerabilities, as access to these resources becomes increasingly competitive and costly. The use of fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, exemplifies this. Reserves are demonstrably diminishing, prompting concerns about long-term energy security and driving exploration into more remote and environmentally sensitive regions to maintain supply.

The consequences of this reduction are multifaceted. Increased extraction costs translate to higher energy prices, impacting economies and consumer spending. Geopolitical tensions arise as nations compete for control over dwindling reserves, potentially leading to conflicts and instability. Furthermore, as readily accessible reserves are exhausted, the extraction process becomes more energy-intensive and environmentally damaging, exacerbating the negative impacts associated with these resources. For example, the extraction of tar sands requires substantial energy inputs and generates significant environmental pollution.

Understanding the link between depletion and the definition of what constitutes a non-renewable energy source is crucial for formulating sustainable energy policies. Recognizing the finite nature of these resources necessitates a transition to renewable alternatives. This transition mitigates the risks associated with depletion, reduces environmental impact, and fosters long-term energy security. Ignoring the depletion factor risks perpetuating reliance on a finite resource base, with potentially severe economic, geopolitical, and environmental consequences.

2. Finite Quantity

A defining characteristic of power generation methods that do not qualify as sustainable is the inherent limitation in the amount of raw materials available. The presence of a fixed, exhaustible supply is a fundamental reason why resources like coal, oil, natural gas, and uranium are excluded from the renewable category. Unlike solar, wind, or hydroelectric power, which harness continuous or rapidly replenished natural processes, the Earth’s reserves of these materials are demonstrably limited. Their use inevitably leads to their depletion.

The consequence of a restricted quantity is multifaceted. As readily accessible reserves are exhausted, extraction becomes more challenging, expensive, and environmentally damaging. This is evident in the increasing exploitation of unconventional sources like shale gas through fracking, which carries significant environmental risks. Furthermore, dependence on finite resources creates strategic vulnerabilities for nations reliant on imports, potentially leading to geopolitical instability and economic dependence. The global oil market serves as a constant reminder of the economic and political ramifications of relying on a resource with a limited global distribution.

Ultimately, understanding the constraint of finite quantity is paramount for transitioning to a more sustainable energy future. The exhaustible nature of these resources mandates a shift towards alternatives that utilize constantly replenishing natural flows. Ignoring this fundamental principle risks perpetuating dependence on a resource base destined for eventual exhaustion, with far-reaching economic, environmental, and social repercussions.

3. Carbon Emission

The release of carbon-containing compounds, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2), into the atmosphere is a critical factor differentiating exhaustible power generation methods from sustainable alternatives. The magnitude of these emissions, associated with combustion or other processes, directly impacts the global climate and underscores the environmental limitations.

- Combustion Processes

The burning of fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, represents the primary source of carbon emissions in the energy sector. These fuels, composed of hydrocarbons, release CO2 and other greenhouse gases when oxidized to generate heat and electricity. The sheer scale of fossil fuel consumption for energy production makes this a dominant contributor to climate change. For instance, coal-fired power plants are notoriously carbon-intensive, releasing significantly more CO2 per unit of energy generated compared to natural gas or renewable sources. The widespread reliance on combustion processes necessitates a transition towards energy sources with minimal or zero carbon emissions.

- Extraction and Processing

Beyond the immediate act of combustion, the extraction, processing, and transportation of fossil fuels also contribute to carbon emissions. Methane leakage during natural gas extraction, transportation of crude oil, and energy consumed in refining processes all add to the overall carbon footprint. These indirect emissions are often overlooked but represent a substantial component of the total environmental impact. The exploitation of unconventional fossil fuels, such as tar sands and shale gas, often involves more energy-intensive extraction methods, further increasing the carbon intensity.

- Long-Term Climate Impacts

The accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere from non-renewable energy sources has profound and long-lasting consequences for the global climate. Increased greenhouse gas concentrations trap heat, leading to rising global temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events. These climate impacts disrupt ecosystems, threaten human health, and undermine economic stability. The long atmospheric lifetime of CO2 means that even drastic reductions in emissions today will not immediately reverse the effects of past emissions, highlighting the urgency of transitioning to sustainable energy sources.

- Alternative Assessment Metrics

Beyond simply quantifying total emissions, alternative metrics such as carbon intensity (emissions per unit of energy produced) are useful for comparing the environmental performance of different energy sources. Life-cycle assessments that consider the entire chain of activities, from resource extraction to end-use, provide a more comprehensive picture of the environmental impact. Understanding these metrics allows for a more nuanced evaluation of energy options and informs strategies for mitigating climate change. The development and adoption of carbon capture and storage technologies may offer a means of reducing emissions from fossil fuel power plants, but their effectiveness and cost-competitiveness remain subjects of ongoing research and debate.

The significant carbon emissions associated with power generation methods failing to meet the criteria of renewability are a central argument for transitioning to energy sources that do not release substantial quantities of greenhouse gases. The urgency of addressing climate change demands a rapid shift towards sustainable and low-carbon alternatives, and the minimization of emissions from current resource consumption.

4. Geological Formation

The geological origin and formation processes are crucial determinants in classifying energy sources as non-renewable. Resources requiring millions of years to develop through geological forces fall into this category, directly contrasting with the rapidly replenishable nature of sustainable alternatives.

- Fossil Fuel Genesis

The creation of fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, involves the transformation of organic matter under intense pressure and heat over extended geological periods. Coal originates from accumulated plant material in swamp environments, while oil and natural gas form from marine organisms deposited on the seafloor. These processes require millions of years to occur, far exceeding the timescale of human civilization. The protracted formation time renders these resources effectively non-renewable on a human timescale.

- Uranium Ore Development

Uranium, used in nuclear power, is another resource with a geological origin. Uranium ore deposits are formed through complex geological processes involving the concentration of uranium-bearing minerals over millions of years. The formation of these deposits is dependent on specific geological conditions and is not a process that can be readily replicated or accelerated. The finite nature of uranium ore reserves underscores its classification as a non-renewable energy source, despite its lower carbon emissions compared to fossil fuels.

- Extraction Limitations

The geological formation processes dictate not only the availability but also the accessibility of non-renewable resources. Extraction often requires significant technological intervention and can be environmentally disruptive. For example, deep-sea oil drilling and mountain-top removal coal mining pose substantial environmental risks. The physical constraints imposed by geological formations limit the rate at which these resources can be extracted, further reinforcing their non-renewable character.

- Resource Distribution

Geological processes also determine the geographical distribution of non-renewable resources. Certain regions are endowed with abundant reserves of fossil fuels or uranium ore, while others lack these resources entirely. This uneven distribution creates geopolitical dependencies and vulnerabilities, as nations compete for access to these finite supplies. The strategic importance of regions rich in non-renewable resources has historically led to conflicts and political instability.

The protracted timescales involved in the formation of fossil fuels and uranium ore deposits, coupled with extraction limitations and uneven distribution, decisively place these resources outside the realm of sustainable energy. Their reliance as primary energy sources presents long-term challenges related to resource depletion, environmental degradation, and geopolitical instability, highlighting the need for transitioning to renewable alternatives.

5. Limited Supply

The inherent constraint of a finite quantity is a defining characteristic that excludes certain energy sources from the renewable category. Non-renewable resources, such as fossil fuels and uranium, exist in demonstrably limited quantities within the Earth’s crust. This limitation dictates that their extraction and consumption will ultimately lead to depletion, contrasting sharply with renewable sources that harness perpetually available natural processes. The concept of a limited supply is thus integral to understanding what differentiates exhaustible resources from sustainable alternatives.

The consequences of this fixed supply are multifaceted. As readily accessible reserves are depleted, extraction becomes more challenging and expensive, requiring the exploitation of unconventional sources with greater environmental impacts. For example, the shift towards deepwater drilling and tar sands extraction illustrates the increasing difficulty in accessing conventional oil reserves. Furthermore, a limited supply creates strategic vulnerabilities for nations reliant on imports, leading to geopolitical tensions and economic dependencies. The global competition for oil and natural gas resources exemplifies this dynamic. Understanding the implications of a limited supply is crucial for informing energy policy and investment decisions, prompting a transition towards more sustainable and resilient energy systems.

In summary, the characteristic of a “limited supply” is inextricably linked to the definition of “what is not a source of renewable energy.” It underscores the unsustainable nature of relying on finite resources for long-term energy needs. The recognition of this limitation necessitates a shift towards renewable energy sources that are continuously replenished, mitigating the risks associated with depletion, environmental degradation, and geopolitical instability. The practical significance lies in the imperative to develop and deploy renewable energy technologies at scale, ensuring a secure and sustainable energy future.

6. Environmental Impact

The operational definition of an energy source’s non-renewability is inextricably linked to its environmental consequences. Energy generation methods that deplete natural resources also frequently inflict significant ecological harm. The extraction, processing, and utilization of fossil fuels, for example, induce a range of adverse environmental effects. These impacts span from habitat destruction during mining and drilling operations to air and water pollution arising from combustion and waste disposal. The release of greenhouse gases contributes to climate change, manifesting in rising global temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events. The environmental burden associated with exhaustible resources is a primary reason why they are deemed unsustainable. A case in point is the environmental degradation caused by coal mining, which can lead to soil erosion, water contamination, and loss of biodiversity.

Further examination reveals the long-term repercussions of relying on these sources. Acid rain, caused by sulfur dioxide emissions from coal-fired power plants, damages forests and aquatic ecosystems. Oil spills, whether from tanker accidents or offshore drilling operations, contaminate marine environments, harming wildlife and disrupting food chains. Nuclear waste disposal poses a persistent challenge, requiring long-term storage solutions to prevent radioactive contamination. The scale and complexity of these environmental problems necessitate a comprehensive assessment of the full life-cycle impacts of energy production, from resource extraction to waste management. Improved environmental regulations and technological advancements can mitigate some of these negative effects, but they cannot eliminate them entirely.

In conclusion, the significant environmental impact associated with certain energy sources is a critical factor in determining their non-renewable status. The depletion of natural resources and the associated environmental degradation underscore the need for a transition towards sustainable energy alternatives. By prioritizing energy sources with minimal environmental impact, it is possible to mitigate climate change, protect ecosystems, and ensure a more sustainable future. The practical significance lies in the imperative to develop and implement energy policies that incentivize the adoption of renewable energy technologies and discourage reliance on environmentally damaging non-renewable resources.

7. Non-Sustainable

The concept of “non-sustainable” is intrinsically linked to the identification of power generation methods that are not renewable. Resources designated as unsustainable possess characteristics that preclude their perpetual use without detrimental consequences to the environment or resource availability. This designation carries significant implications for energy policy and long-term environmental stewardship.

- Resource Depletion

A primary indicator of non-sustainability is the depletion of finite resources. Exhaustible energy sources, such as fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas) and uranium, are present in limited quantities within the Earth’s crust. Their extraction and consumption outpace natural replenishment processes, leading to eventual exhaustion of reserves. This depletion not only poses a long-term energy security risk but also necessitates increasingly disruptive and environmentally damaging extraction techniques. Examples include deep-sea drilling for oil and mountaintop removal coal mining. These practices extract resources but simultaneously degrades environment.

- Environmental Degradation

Power generation methods deemed non-sustainable often inflict significant environmental damage. The combustion of fossil fuels releases greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change and its associated consequences, such as rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and disruptions to ecosystems. Furthermore, activities like mining and drilling can cause habitat destruction, water pollution, and soil contamination. The long-term environmental costs associated with these practices outweigh any short-term economic benefits, rendering them unsustainable from a broader perspective. For instance, the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 caused immense damage to the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem.

- Economic Vulnerability

Reliance on non-sustainable energy sources can create economic vulnerabilities. Price volatility in global fossil fuel markets can disrupt national economies, particularly those heavily dependent on imports. Depletion of domestic reserves can lead to increased reliance on foreign sources, creating geopolitical dependencies and potential security risks. Furthermore, the long-term costs associated with environmental remediation and healthcare related to pollution from these sources can strain public finances. Countries heavily reliant on coal exports, for example, face economic challenges as the global demand for coal declines due to environmental concerns.

- Social Inequity

The use of non-sustainable energy sources can exacerbate social inequalities. Communities located near extraction sites often bear the brunt of environmental pollution, leading to health problems and reduced quality of life. The economic benefits associated with resource extraction may not be evenly distributed, leaving local populations marginalized and disenfranchised. Furthermore, the impacts of climate change disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, exacerbating existing inequalities. For instance, low-income communities often reside in areas more susceptible to flooding and extreme weather events caused by climate change.

These interconnected facetsresource depletion, environmental degradation, economic vulnerability, and social inequitycollectively define the concept of “non-sustainable” in the context of power generation. Addressing these challenges requires a fundamental shift away from exhaustible resources and towards renewable energy systems that are environmentally sound, economically viable, and socially equitable. The transition towards sustainablity must be considered at every level, small and large scale.

Frequently Asked Questions About Non-Renewable Energy

This section addresses common queries and misconceptions surrounding energy sources that do not qualify as renewable. The information presented aims to provide clarity on the characteristics and implications of utilizing non-renewable resources.

Question 1: What fundamentally distinguishes a non-renewable energy source?

The primary distinction lies in the rate of replenishment. Non-renewable resources, such as fossil fuels and uranium, are depleted at a rate significantly exceeding their natural regeneration. These resources exist in finite quantities and cannot be sustainably used over extended periods.

Question 2: How does the geological formation process factor into the non-renewable classification?

Non-renewable resources typically require millions of years to form through geological processes involving intense pressure and heat. This protracted formation timescale contrasts sharply with renewable resources, which are naturally replenished within human timescales.

Question 3: What are the primary environmental consequences associated with non-renewable energy use?

The use of non-renewable energy sources often results in significant environmental impacts, including greenhouse gas emissions, air and water pollution, habitat destruction, and resource depletion. These impacts contribute to climate change and ecological degradation.

Question 4: Does nuclear power qualify as a renewable energy source?

Nuclear power utilizes uranium, a finite resource extracted from the Earth’s crust. While nuclear power generates electricity with relatively low carbon emissions, the finite nature of uranium and the challenges associated with nuclear waste disposal exclude it from the renewable category.

Question 5: Are there any measures to mitigate the environmental impacts of non-renewable energy?

Various mitigation measures exist, including carbon capture and storage technologies, improved energy efficiency, and stricter environmental regulations. However, these measures cannot eliminate the fundamental unsustainability of relying on finite resources.

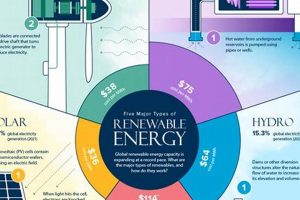

Question 6: What are the alternatives to non-renewable energy sources?

Renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and biomass, offer sustainable alternatives to non-renewable resources. These sources harness naturally replenishing energy flows and have significantly lower environmental impacts.

In summary, understanding the limitations and consequences associated with these energy sources is essential for informed energy planning and promoting a transition to sustainable alternatives.

The following sections will delve into the future of energy solutions and the role of renewable resources in a sustainable world.

Concluding Remarks on Non-Renewable Energy Sources

This exposition has meticulously examined the attributes that define sources as not qualifying for the “renewable” designation. Finite reserves, prolonged geological formation timelines, significant carbon emissions, and consequential environmental impacts collectively characterize these resources, underscoring their unsustainable nature. Understanding these defining traits is paramount for informed energy policy and strategic decision-making.

The imperative to transition towards sustainable energy solutions remains a critical global challenge. Recognizing the limitations and ramifications associated with unsustainable power generation methods is a fundamental step towards forging a more resilient and environmentally responsible energy future. Continued research, technological innovation, and policy implementation are essential to facilitate this transition and mitigate the long-term risks associated with reliance on limited resources. The path forward necessitates a commitment to exploring and implementing renewable alternatives to achieve global energy security and environmental integrity.