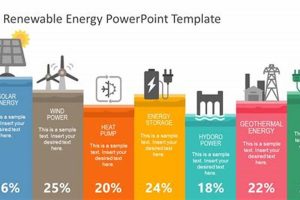

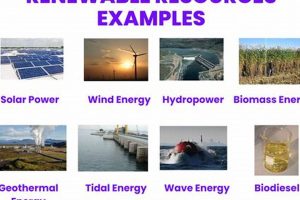

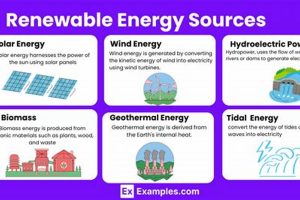

Resources that replenish naturally within a human lifespan are considered sustainable. These materials, derived from the environment, are continuously restored by ecological cycles or other natural processes. Examples include solar energy, wind power, geothermal energy, and biomass, along with resources like forests and freshwater, provided their use is carefully managed to prevent depletion.

The significance of utilizing such resources lies in their potential to mitigate environmental degradation and promote long-term ecological balance. Their sustainable exploitation reduces reliance on finite reserves, thereby minimizing pollution associated with extraction, processing, and combustion. Historically, societies have depended on these resources; however, a shift towards unsustainable practices necessitates a renewed focus on their responsible management for future generations.

Understanding the principles of sustainability and resource management is vital for comprehending the topics discussed in the subsequent sections. These principles directly inform strategies for energy production, environmental conservation, and economic development, particularly in the context of long-term ecological and societal well-being.

Practical Considerations for Renewable Resource Management

The effective utilization of naturally replenishing resources requires a comprehensive understanding of ecological systems and responsible stewardship. The following guidelines facilitate the sustainable application of these resources.

Tip 1: Implement Adaptive Management Strategies: Environmental conditions are subject to constant change. Adaptive management allows for flexible adjustments to resource utilization practices based on monitoring data and evolving scientific understanding. This ensures resilience against unforeseen events and optimizes resource yield over time.

Tip 2: Prioritize Ecosystem Integrity: Resource extraction should minimize disruption to ecological processes. Maintaining biodiversity, protecting watersheds, and preserving habitats are crucial for the long-term health and productivity of renewable systems. Conduct thorough environmental impact assessments prior to any resource development.

Tip 3: Invest in Research and Development: Continuous innovation is essential for improving the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of resource utilization technologies. Support research initiatives focused on renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and ecological restoration to enhance resource management practices.

Tip 4: Promote Community Engagement: Local communities often possess valuable knowledge regarding resource management and possess a vested interest in their sustainable use. Actively involve stakeholders in decision-making processes to foster a sense of ownership and ensure equitable distribution of benefits.

Tip 5: Establish Robust Monitoring Programs: Comprehensive monitoring systems are necessary to track resource availability, assess environmental impacts, and evaluate the effectiveness of management strategies. Regular data collection and analysis provide the basis for informed decision-making and adaptive management.

Tip 6: Enforce Strict Regulatory Frameworks: Clear and enforceable regulations are crucial for preventing overexploitation and ensuring responsible resource use. These frameworks should be based on scientific evidence and regularly updated to reflect changing environmental conditions and technological advancements.

Effective resource management necessitates a holistic and proactive approach, integrating ecological principles, technological innovation, and community involvement. These strategies provide a pathway towards sustainable utilization and preservation for future generations.

Implementing these considerations is vital for the discussion of effective and sustainable management practices detailed in the following sections.

1. Replenishment within lifespan

The concept of “replenishment within a lifespan” forms a fundamental pillar supporting the overall “renewable natural resources definition.” This temporal constraint distinguishes these resources from finite or slowly regenerating assets. The rate at which a resource renews dictates its classification as sustainable and influences management strategies.

- Rate of Renewal and Sustainability

The speed at which a resource recovers is intrinsically linked to its sustainable use. If consumption exceeds the renewal rate, the resource effectively becomes non-renewable, leading to depletion. Solar energy, continuously available, represents the ideal scenario. Forests, while renewable, require decades to mature, necessitating careful management to prevent deforestation and ensure future supply.

- Human Impact and Renewal Rates

Human activities can significantly impact the replenishment rates of natural resources. Pollution, habitat destruction, and unsustainable harvesting practices can impede or halt natural renewal processes. Overfishing, for instance, reduces fish populations and disrupts marine ecosystems, diminishing the stock’s ability to regenerate within a human lifespan. Addressing these impacts requires conservation efforts and responsible resource management.

- Time Scales and Resource Classification

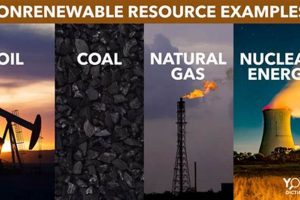

The classification of a resource as renewable depends on the timescale of its replenishment relative to human needs and consumption patterns. Resources that take centuries to regenerate, such as certain mineral deposits, are generally considered non-renewable despite their eventual renewal. This distinction underscores the practical limitations and the importance of prioritizing resources that demonstrably replenish within a reasonable timeframe.

- Technological Advancements and Resource Availability

Technological innovation can influence the perceived availability of resources that are considered to have “replenishment within lifespan”. For example, advanced water filtration techniques might allow for the more efficient use of existing freshwater resources. Similarly, improvements in photovoltaic cell technology can increase the harvesting of solar energy. While technology can extend the lifespan and utility of such resources, it does not replace the importance of proper management and conservation efforts.

In summation, the principle of replenishment within a human lifespan serves as a crucial criterion in defining and managing renewable natural resources. The rate of renewal, the impact of human activities, and the influence of technological advancements all contribute to the overall sustainability and long-term availability of these essential components of the natural environment.

2. Ecological cycle restoration

The concept of ecological cycle restoration is intrinsically linked to the definition of renewable natural resources. The continued availability of these resources hinges on the integrity and functionality of the natural cycles that replenish them. Restoration efforts aim to re-establish these cycles, ensuring the long-term provision of essential resources.

- Water Cycle Restoration and Freshwater Availability

The water cycle, encompassing evaporation, precipitation, and runoff, is crucial for maintaining freshwater supplies. Deforestation and urbanization disrupt this cycle, leading to decreased infiltration and increased runoff, resulting in water scarcity and flooding. Restoration projects, such as reforestation and wetland restoration, enhance water infiltration, replenish groundwater aquifers, and moderate water flow, securing freshwater resources. Example: Replanting native vegetation in a watershed improves water quality and availability downstream, providing a sustainable water supply for human consumption and agricultural use.

- Nutrient Cycle Restoration and Soil Fertility

Nutrient cycles, including the nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon cycles, are essential for soil fertility and plant growth. Intensive agriculture and deforestation deplete soil nutrients, reducing land productivity. Restoration practices, such as crop rotation, cover cropping, and composting, replenish soil nutrients, improve soil structure, and enhance carbon sequestration, promoting sustainable agriculture. Example: Implementing no-till farming practices reduces soil erosion and enhances carbon storage in agricultural soils, leading to improved soil fertility and crop yields.

- Carbon Cycle Restoration and Climate Regulation

The carbon cycle governs the exchange of carbon between the atmosphere, oceans, and terrestrial ecosystems. Deforestation and fossil fuel combustion release excessive amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. Restoration efforts, such as reforestation, afforestation, and wetland restoration, sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, mitigating climate change and enhancing ecosystem resilience. Example: Restoring mangrove forests sequesters significant amounts of carbon and provides coastal protection from storm surges, contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

- Ecosystem Restoration and Biodiversity Enhancement

Ecosystem restoration encompasses a wide range of activities aimed at rehabilitating degraded ecosystems, including forests, grasslands, and wetlands. Restoration projects enhance biodiversity, improve ecosystem function, and increase the resilience of ecosystems to environmental stressors. Restoring diverse ecosystems ensures the long-term availability of various natural resources, from timber and food to clean water and air. Example: Removing invasive species and reintroducing native plants in a degraded grassland restores habitat for native wildlife and improves grazing capacity for livestock, promoting biodiversity and sustainable land use.

The successful integration of ecological cycle restoration into resource management strategies is paramount for ensuring the sustained availability of renewable natural resources. These practices not only enhance resource productivity but also contribute to overall ecosystem health and resilience, thereby supporting long-term environmental sustainability.

3. Sustainable use imperative

The “sustainable use imperative” constitutes a non-negotiable component of the “renewable natural resources definition.” Renewable resources, by their very nature, possess the capacity for regeneration within a human timescale. However, this inherent renewability is contingent upon responsible and judicious utilization. Overexploitation negates the renewable characteristic, effectively transforming a replenishable resource into a finite one. A prime example is deforestation; while forests can regenerate, unsustainable logging practices lead to irreversible habitat loss, soil erosion, and diminished carbon sequestration capacity, negating their renewable nature. Therefore, sustainable use is not merely an advisory principle but an essential condition for maintaining the renewable status of these resources.

The practical significance of understanding this connection lies in shaping resource management policies and practices. Policies that prioritize short-term economic gains over long-term ecological health frequently result in the depletion of renewable resources. Conversely, strategies that incorporate ecological principles, promote conservation, and encourage efficient utilization can ensure the continued availability of these resources. The implementation of quotas in fisheries, for example, aims to prevent overfishing and allow fish populations to regenerate. Similarly, promoting renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, reduces reliance on fossil fuels and mitigates greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to climate stability.

In conclusion, the “sustainable use imperative” serves as a critical qualifier within the “renewable natural resources definition.” Without a commitment to responsible utilization, the potential benefits of renewability are unrealized. Addressing the challenges associated with balancing economic development and environmental conservation requires a fundamental shift in perspective, recognizing that the long-term prosperity of human societies is inextricably linked to the sustainable management of these vital resources.

4. Environmental impact reduction

The principle of environmental impact reduction is fundamentally interwoven with the “renewable natural resources definition.” While resources may possess the capacity for natural replenishment, the processes involved in their extraction, processing, and utilization invariably exert an influence on the environment. The extent of this influence directly determines the sustainability of the resource’s use and its alignment with the core tenets of the definition. For instance, while hydroelectric power harnesses a renewable water source, the construction of dams can disrupt aquatic ecosystems, alter river flow regimes, and displace human populations. Therefore, the pursuit of reduced environmental impact is not merely an ancillary benefit but rather a prerequisite for truly sustainable resource utilization. A significant factor in evaluating renewable resources like wind or solar power is the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions compared to fossil fuels. However, careful consideration must also be given to their impact on wildlife and land use.

Practical applications of this understanding manifest in the development and implementation of environmentally conscious technologies and resource management strategies. Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) play a crucial role in quantifying the environmental footprint of a resource from extraction to disposal, enabling informed decision-making and the identification of opportunities for impact minimization. Additionally, employing best management practices in forestry, agriculture, and fisheries ensures that resource extraction occurs in a manner that minimizes habitat disruption, soil erosion, and water pollution. For example, employing selective logging practices in forestry operations limits disturbance compared to clear-cutting, allowing for faster forest regeneration and reduced impacts on biodiversity. Another example is the application of integrated pest management in agriculture, which reduces reliance on synthetic pesticides, thereby mitigating negative effects on beneficial insects and water quality.

In conclusion, the “renewable natural resources definition” is incomplete without explicit consideration of environmental impact. The reduction of these impacts is not merely desirable but essential for ensuring the long-term availability and sustainability of renewable resources. Balancing resource utilization with environmental stewardship requires a comprehensive and integrated approach, incorporating life cycle assessments, best management practices, and a commitment to continuous improvement. Failure to prioritize environmental impact reduction undermines the fundamental principles of sustainability and jeopardizes the future availability of these vital resources.

5. Long-term availability secured

Securing long-term availability represents the ultimate goal in the responsible management of replenishable resources. It signifies the practical manifestation of a resource truly meeting the criteria inherent within its definition. Its absence renders any claim of renewability questionable, underscoring its essential status.

- Resource Monitoring and Assessment

Long-term availability necessitates rigorous and sustained resource monitoring and assessment. This involves the continuous collection and analysis of data pertaining to resource stocks, regeneration rates, and environmental impacts. Without accurate and up-to-date information, informed decision-making becomes impossible, increasing the risk of overexploitation and resource depletion. For example, the monitoring of groundwater levels and recharge rates is crucial for ensuring the sustainable use of aquifers, preventing saltwater intrusion and land subsidence. Fisheries management relies heavily on stock assessments to determine sustainable catch limits, protecting fish populations from collapse.

- Adaptive Management Strategies

The concept also requires the implementation of adaptive management strategies. Environmental conditions and resource demands are constantly evolving, necessitating flexible and responsive management approaches. Adaptive management involves continuous learning and adjustment based on monitoring data and scientific understanding. This allows for proactive adaptation to unforeseen challenges and ensures the long-term resilience of resource systems. For example, water resource managers may adjust reservoir release schedules in response to changing weather patterns, optimizing water supply for various users while maintaining ecological flows.

- Legal and Institutional Frameworks

Effective legal and institutional frameworks are indispensable for securing long-term resource availability. Clear regulations, property rights, and enforcement mechanisms are essential for preventing overexploitation and promoting responsible resource use. These frameworks must be designed to balance the interests of various stakeholders, including resource users, conservation groups, and government agencies. For example, national parks and protected areas provide legal safeguards for biodiversity and ecosystem services, ensuring the long-term preservation of natural resources. Similarly, water rights systems allocate water resources among competing users, promoting equitable and sustainable water management.

- Community Engagement and Participation

It relies upon active community engagement and participation. Local communities often possess valuable knowledge regarding resource management and a strong vested interest in their sustainable use. Involving stakeholders in decision-making processes fosters a sense of ownership and responsibility, promoting greater compliance with regulations and enhancing the effectiveness of management strategies. Community-based forestry initiatives, for example, empower local communities to manage forest resources sustainably, providing them with economic benefits while conserving biodiversity and protecting watersheds.

These facets must intertwine to guarantee that natural resources remain not only renewable but also available for future generations. It demands a proactive, informed, and collaborative approach, integrating scientific knowledge, adaptive management, and community involvement. Failure to prioritize these elements jeopardizes the integrity of ecosystems and the long-term well-being of human societies. By establishing robust frameworks for resource monitoring, adaptive management, legal protection, and community participation, societies can effectively secure the long-term availability of replenishable resources, ensuring their continued contribution to environmental sustainability and economic prosperity.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following questions address common inquiries and misconceptions regarding the definition of renewable natural resources, providing clarification on key aspects and related concepts.

Question 1: What fundamentally differentiates a renewable natural resource from a non-renewable one?

The critical distinction lies in the rate of replenishment. A renewable resource is replenished naturally within a human lifespan, whereas a non-renewable resource either does not replenish or does so at a rate far exceeding human timescales.

Question 2: Does the term ‘renewable’ guarantee unlimited availability?

No. The renewable status of a resource is contingent upon sustainable management practices. Overexploitation can deplete even renewable resources, negating their renewable characteristic.

Question 3: How do ecological cycles relate to the definition of renewable resources?

Ecological cycles, such as the water, carbon, and nutrient cycles, are integral to the replenishment of many renewable resources. Disruptions to these cycles can impair resource renewal rates and compromise their sustainability.

Question 4: What role does technology play in enhancing the availability of such resources?

Technology can improve the efficiency of resource utilization and access, but it cannot replace the need for sustainable management practices. Technological advancements can extend resource lifespans but do not alter the fundamental constraints of renewability.

Question 5: How is environmental impact considered within the context of “renewable natural resources definition?”

Environmental impact reduction forms an integral part. While resources may be replenished naturally, processes linked to their extraction and use invariably bear an impact. Lessening the impact is essential for sustainable use and its alignment with the definition.

Question 6: Why is long-term monitoring essential for ensuring resource availability?

Consistent monitoring allows for tracking resource stocks, regeneration rates, and the effects of management strategies. The data collected guides informed decision-making, enabling adaptive management and minimizing the risk of resource depletion.

In summary, understanding renewability necessitates considering rate, impacts, and monitoring to ensure that resources remain viable for future requirements.

Subsequent sections will explore practical strategies for managing these resources effectively.

Conclusion

This exploration of “renewable natural resources definition” underscores the critical interplay between natural replenishment, responsible management, and environmental stewardship. The definition extends beyond simple renewability, encompassing sustainable utilization, ecological cycle restoration, and a commitment to minimizing environmental impact. Long-term availability is contingent upon the successful integration of these principles into resource management practices.

The future sustainability of human societies depends on a rigorous application of this definition. Failure to recognize the constraints and responsibilities inherent in the use of these resources will inevitably lead to their depletion, with potentially catastrophic consequences for the environment and human well-being. A renewed commitment to informed decision-making, sustainable practices, and environmental conservation is essential to secure these essential resources for future generations.