Substances existing in finite quantities on Earth, which cannot be replenished at a rate comparable to their consumption, form a category of vital significance. These materials, once depleted, are essentially unavailable for future use within a human timescale. Familiar instances include fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas, alongside nuclear fuels like uranium. Their formation typically requires millions of years under specific geological conditions.

The significance of understanding the nature of these finite supplies lies in their central role in powering modern society. They fuel industries, provide energy for transportation, and are critical for electricity generation. Throughout history, easy access to these reserves has driven economic growth and technological advancement. However, reliance upon them introduces challenges related to environmental impact and long-term resource security. Their extraction and utilization contribute to pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, influencing climate patterns globally.

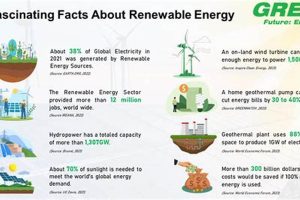

The dependence on this finite inventory necessitates a shift toward alternative energy sources and sustainable practices. This transition requires exploration into the development of renewable technologies, such as solar, wind, and geothermal energy. Furthermore, improvements in energy efficiency and the adoption of circular economy models become crucial elements for mitigating the depletion of these essential, yet limited, commodities.

Considerations Regarding Finite Natural Assets

The responsible management of exhaustible reserves is paramount for ensuring long-term societal stability and environmental preservation. Implementing proactive strategies is vital for mitigating the consequences of their depletion.

Tip 1: Prioritize Energy Efficiency: Enhance energy conservation across all sectors, including industrial processes, transportation systems, and residential buildings. Improved insulation, efficient appliances, and optimized industrial equipment can significantly reduce overall energy consumption.

Tip 2: Invest in Renewable Energy Infrastructure: Allocate resources to develop and deploy renewable energy technologies such as solar, wind, geothermal, and hydroelectric power. Diversifying the energy mix minimizes dependence on a single, limited source and promotes a more sustainable energy future.

Tip 3: Promote Research and Development: Support scientific investigations aimed at discovering novel energy sources, improving energy storage capabilities, and enhancing the efficiency of existing renewable technologies. Technological advancements are critical for accelerating the transition to a sustainable energy economy.

Tip 4: Implement Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) Technologies: Develop and deploy technologies that capture carbon dioxide emissions from industrial processes and power plants, preventing them from entering the atmosphere. Carbon capture and storage can play a significant role in mitigating climate change while transitioning away from carbon-intensive sources.

Tip 5: Adopt Circular Economy Principles: Embrace circular economy models that prioritize resource efficiency, waste reduction, and material reuse. Designing products for durability and recyclability minimizes the demand for virgin materials and reduces the environmental impact of waste disposal.

Tip 6: Encourage Sustainable Transportation Options: Promote the use of public transportation, cycling, and walking as alternatives to private vehicle ownership. Investing in public transportation infrastructure and creating pedestrian-friendly environments reduces traffic congestion and lowers greenhouse gas emissions.

Tip 7: Promote responsible consumption and production: Education and awareness campaigns can encourage the public to make responsible choices regarding energy consumption and resource utilization. Supporting policies that promote sustainable consumption patterns helps to reduce overall demand and minimize environmental impact.

Adopting these measures fosters a sustainable future by reducing reliance on dwindling natural endowments, diminishing environmental harm, and ensuring resource availability for upcoming generations.

The implementation of these practices will serve as a cornerstone in the establishment of a more resilient and environmentally conscious society, ensuring the preservation of resources for future generations.

1. Finite Supply

The concept of limited availability is intrinsically linked to understanding “non renewable resources meaning.” The fixed quantity of these materials, coupled with consumption rates, necessitates careful consideration of present use and future access.

- Geological Constraints

The formation of resources like fossil fuels and uranium requires specific geological processes occurring over immense time scales. The Earth’s crust contains a finite amount of the organic material and necessary conditions for their genesis. This inherent geological constraint dictates that no new reserves can be created within a relevant human timeframe. Consequently, the quantity available is a fixed and exhaustible amount.

- Depletion Rates and Consumption Patterns

Global demand drives the extraction and consumption of exhaustible resources. As economies develop and populations grow, the rate at which these resources are utilized increases. The current depletion rate far exceeds any natural replenishment process, leading to a progressive reduction in accessible reserves. This imbalance between consumption and natural regeneration defines the core challenge posed by their limited nature.

- Technological Limits to Extraction

While technological advancements may enhance extraction efficiency, they cannot circumvent the fundamental limitation of total resource quantity. Enhanced recovery methods might extend the lifespan of a particular reserve, but they do not generate new materials. Furthermore, technological limitations place economic constraints on extracting resources from less accessible locations, further restricting the effectively available supply.

- Environmental Consequences of Extraction

The pursuit of exhaustible resources often carries significant environmental repercussions. Extraction processes, such as mining and drilling, can disrupt ecosystems, contaminate water sources, and contribute to habitat destruction. The environmental cost associated with accessing these resources presents an additional constraint on their availability, as societies increasingly recognize the need to balance resource utilization with ecological preservation.

These facets underscore the inherent constraints of “non renewable resources meaning.” The finite geological endowments, accelerated depletion, limits of technology, and related environmental impacts collectively highlight the urgent need for alternative energy sources and sustainable consumption practices. Understanding these factors is paramount for shaping responsible resource management strategies.

2. Fossil Fuels

Fossil fuels represent a significant constituent within the spectrum of finite substances. These materials, derived from the preserved remains of ancient organisms, are primary examples of “non renewable resources meaning” due to their formation timescales exceeding human lifespans and their finite reserves.

- Origin and Composition

Fossil fuels encompass coal, petroleum (crude oil), and natural gas. Coal originates from accumulated plant matter subjected to heat and pressure over millions of years. Petroleum and natural gas derive from marine organisms undergoing similar transformation processes. The composition varies, with coal primarily consisting of carbon, and petroleum and natural gas composed of hydrocarbons. The long-term geological transformations underscore the non-renewable nature.

- Energy Provision and Usage

These fuels are vital for energy production globally. Coal serves as a primary fuel for electricity generation in numerous countries. Petroleum is crucial for transportation, powering vehicles and aircraft. Natural gas is utilized for heating, electricity generation, and industrial processes. Their widespread use highlights their importance, but it also emphasizes the rapid depletion of reserves and associated impacts.

- Environmental Consequences

Combustion of fossil fuels releases greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide. These gases contribute to climate change, driving global warming and altering weather patterns. Additionally, extraction processes, such as mining and drilling, can cause habitat destruction, water contamination, and air pollution. The environmental effects are significant drawbacks.

- Reserve Distribution and Geopolitics

The geographic distribution of these reserves is uneven. Certain regions possess abundant reserves, while others have limited access. This unequal distribution creates geopolitical tensions and influences international relations. Control over fossil fuel resources can confer economic and political advantages, shaping global power dynamics.

The characteristics of fossil fuels, from their origin to their environmental consequences and geopolitical implications, exemplify the core challenges associated with limited resources. Their finite nature and detrimental environmental impact emphasize the urgent need for diversified energy sources and sustainable practices to mitigate future risks and ensure long-term stability.

3. Environmental Impact

The environmental ramifications associated with the extraction, processing, and utilization of materials existing in limited quantities are significant. These effects are intrinsic to understanding the full scope of “non renewable resources meaning,” extending beyond simple resource depletion to encompass ecological and atmospheric consequences.

- Air Pollution

Combustion of fossil fuels, a primary source of energy derived from limited reserves, releases pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, and carbon monoxide into the atmosphere. These pollutants contribute to respiratory illnesses, acid rain, and smog formation. Industrial processes related to resource extraction and refinement further exacerbate air quality degradation. The atmospheric burden from these activities directly stems from the exploitation of finite geological endowments.

- Water Contamination

Mining operations and oil spills introduce toxic chemicals, heavy metals, and hydrocarbons into water systems. Acid mine drainage, a prevalent issue associated with coal mining, contaminates rivers and groundwater, rendering water unusable for human consumption and harming aquatic ecosystems. Fracking, used to extract natural gas, poses risks of groundwater contamination from chemicals used in the process. These incidents highlight the water resource damage arising from reliance on these sources.

- Habitat Destruction

Surface mining, deforestation for resource extraction, and infrastructure development lead to habitat fragmentation and loss of biodiversity. Ecosystems are disrupted, displacing wildlife and reducing the capacity of natural systems to provide ecosystem services. The conversion of natural landscapes into resource extraction sites represents a direct consequence of meeting energy and material demands using environmentally disruptive methods. This transformation of terrain permanently alters ecological structures, impacting flora and fauna.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The burning of fossil fuels releases large quantities of carbon dioxide, a primary greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere. Methane, another potent greenhouse gas, is released during natural gas production and transportation. These emissions contribute to global warming and climate change, resulting in rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and altered precipitation patterns. The amplification of the greenhouse effect directly ties utilization to alterations in global climate systems.

The cumulative effects of air and water pollution, habitat destruction, and greenhouse gas emissions directly link the utilization of these materials to ecological degradation and climate instability. Addressing these challenges requires a transition towards sustainable energy practices and responsible resource management to minimize the environmental footprint and secure ecological integrity.

4. Long Formation

The protracted geological timescales involved in the genesis of specific resources are fundamental to their classification as limited. This extensive formation period, spanning millions of years, is a defining characteristic of “non renewable resources meaning.” It directly influences their scarcity and the challenges associated with sustainable utilization. The lengthy duration needed for their creation contrasts sharply with the rapid rate at which they are currently being consumed, highlighting an unsustainable imbalance. For instance, the formation of fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, requires the accumulation of organic matter, burial under sediment, and subsequent transformation under high pressure and temperature over vast epochs. This prolonged process means that these resources, once depleted, cannot be replenished within a human lifespan or even within many generations.

The significance of recognizing this temporal element is multifaceted. It informs resource management strategies by emphasizing the need for conservation and efficient utilization. The understanding that nature cannot quickly replace what is extracted encourages a transition to alternative, renewable energy sources. Furthermore, this awareness shapes policy decisions regarding resource extraction and consumption. For example, the recognition that crude oil requires millions of years to form has prompted investments in renewable energy technologies such as solar and wind power. Similarly, the slow formation of uranium ore bodies has led to research into nuclear fusion, which offers the potential for a virtually inexhaustible energy source. The practical effect is the promotion of research and development into technologies capable of replacing or extending the availability of what is currently being consumed.

In conclusion, the long formation period associated with certain geological deposits is a critical component of their non-renewable designation. This protracted timeline directly contributes to their finite availability and underscores the urgent need for responsible resource management. Addressing the challenges posed by depleting supplies requires a comprehensive approach that incorporates conservation, innovation, and a fundamental shift towards sustainable energy practices to reduce reliance on resources that nature requires millennia to create. The temporal aspect is not merely an academic detail but a practical imperative for guiding future resource policies.

5. Depletion Rates

Depletion rates are intrinsically linked to the understanding of “non renewable resources meaning,” serving as a critical quantitative measure of their finite nature and the urgency of addressing their unsustainable utilization. The rate at which these substances are extracted and consumed directly determines their lifespan, underscoring the core principle that they cannot be replenished at a rate comparable to their use. For instance, the global consumption of petroleum products far exceeds the rate at which new petroleum reserves are discovered, leading to a steady decline in proven reserves relative to demand. This trend exemplifies how depletion rates directly impact the long-term availability of these resources. Factors influencing depletion rates include population growth, industrialization, technological advancements that enable more efficient extraction, and government policies that either encourage or discourage consumption. Each element contributes to the overall speed at which these finite resources are exhausted, thereby affecting their economic viability and societal impact.

The importance of monitoring and understanding these rates extends to several practical implications. Accurate depletion models enable governments and industries to project future resource availability, informing strategic decisions related to energy planning, infrastructure development, and investment in alternative energy sources. For example, projections of declining natural gas reserves have prompted many nations to invest in renewable energy infrastructure and explore alternative fuel sources, such as hydrogen or biofuels. Furthermore, understanding depletion rates helps policymakers design effective conservation strategies and implement regulations to reduce wasteful consumption. The imposition of fuel efficiency standards for vehicles or the implementation of carbon pricing mechanisms serves as instruments to curb demand and extend the lifespan of finite resources. The practical consequences of neglecting depletion rates include economic instability, geopolitical tensions, and environmental degradation, underlining the need for proactive management.

In summary, depletion rates represent a central component in defining “non renewable resources meaning” because they quantify the extent to which these resources are being exhausted and influence the trajectory of their future availability. The challenge lies in balancing economic development with responsible resource management to mitigate the adverse consequences of unsustainable consumption patterns. Addressing this challenge requires a multifaceted approach, including technological innovation, policy interventions, and changes in societal behavior to promote conservation and sustainability. Only through a concerted effort can society hope to transition towards a more sustainable and equitable future, minimizing the risks associated with reliance on finite resources.

6. Future Scarcity

The potential for future scarcity is an inherent and critical dimension of “non renewable resources meaning.” This anticipation of limited future availability stems directly from the fundamental characteristic of these substances: their finite quantity and the inability to replenish them at a rate commensurate with human consumption. The relationship is causal; depletion, driven by extraction and use, inevitably leads to reduced future availability. This prospect of diminished access underscores the importance of understanding this material category, as it shapes economic strategies, environmental policies, and geopolitical dynamics. The reliance on coal for electricity generation, for instance, is a prime example. Current reserves are substantial, but continued dependence without a transition to alternative energy sources will ultimately lead to a situation where the resource becomes increasingly difficult and expensive to obtain. This increasing difficulty is directly linked to the notion of future scarcity.

The implications of this potential shortage extend across various sectors. Industries dependent on fossil fuels face increasing costs and uncertainty regarding supply, potentially impacting production and economic growth. Transportation systems reliant on petroleum products confront the challenge of finding alternative fuels and adapting infrastructure. Furthermore, geopolitical tensions may intensify as nations compete for dwindling resources, potentially leading to conflicts and instability. The transition to renewable energy sources represents a practical response to mitigate these risks. Investing in solar, wind, geothermal, and other alternative sources helps reduce reliance on materials with finite reserves, lessening the potential for future shortages. Moreover, improving energy efficiency and adopting circular economy principles can further extend the lifespan of existing supplies, delaying the onset of scarcity and reducing its associated consequences.

In conclusion, future scarcity is not merely a theoretical possibility but an inevitable consequence of the finite nature of certain geological deposits and current consumption patterns. Recognizing this reality is essential for informed decision-making and responsible resource management. The challenge lies in proactively mitigating the risks associated with declining availability through innovation, policy interventions, and societal shifts towards more sustainable practices. Ignoring the prospect of diminished future access carries significant economic, environmental, and social implications, highlighting the urgency of addressing this critical aspect of “non renewable resources meaning.”

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the nature, implications, and management of substances available in limited quantities on Earth.

Question 1: What fundamentally defines a substance as falling under “non renewable resources meaning?”

A resource is categorized as such if its rate of natural replenishment is negligible compared to the rate of its consumption by human activities. This implies that once extracted and utilized, the resource is effectively unavailable for future use within a relevant human timescale.

Question 2: How do fossil fuels exemplify the concept of “non renewable resources meaning?”

Fossil fuels, including coal, oil, and natural gas, are formed over millions of years from the compressed remains of ancient organisms. Their current extraction and consumption rates far exceed their natural formation rate, making them a prime example of this.

Question 3: What are the primary environmental consequences associated with the utilization of resources aligning with “non renewable resources meaning?”

The extraction and combustion of these substances contribute to air and water pollution, habitat destruction, and greenhouse gas emissions. These environmental impacts exacerbate climate change and degrade ecosystems.

Question 4: How does the geographic distribution of deposits factor into the understanding of “non renewable resources meaning?”

The uneven distribution of deposits across the globe creates geopolitical tensions and influences international relations. Control over resource-rich regions can confer economic and political advantages, leading to competition and potential conflicts.

Question 5: What alternatives exist to mitigate reliance on materials falling under “non renewable resources meaning?”

Diversifying energy sources by investing in renewable energy technologies, such as solar, wind, geothermal, and hydroelectric power, reduces dependence on limited reserves. Enhancing energy efficiency and adopting circular economy models further promote sustainability.

Question 6: How can individuals contribute to the responsible management of substances aligning with “non renewable resources meaning?”

Individuals can promote sustainable practices by conserving energy, reducing consumption, supporting policies that encourage renewable energy development, and advocating for responsible resource management.

Understanding the finite nature and associated challenges is crucial for shaping sustainable practices and promoting a more resilient future. Responsible stewardship is essential for ensuring resource availability for generations to come.

The next section will explore strategies for promoting the responsible and sustainable management of such substances.

Non Renewable Resources Meaning

The exploration of “non renewable resources meaning” reveals a fundamental challenge facing contemporary society. Their finite nature, coupled with significant environmental and geopolitical implications, necessitates a reassessment of current consumption patterns and energy strategies. Reliance on these sources presents inherent risks related to resource depletion, ecological degradation, and global instability.

Addressing these challenges demands a comprehensive and proactive approach. Innovation in renewable energy technologies, coupled with policy interventions and a shift towards sustainable practices, is essential for mitigating the risks associated with their diminished availability. The responsible stewardship of Earth’s finite endowments is not merely an option but a critical imperative for ensuring a stable and prosperous future.

![Top 5: What are Renewable Resources? [Explained] Renewable Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future | Clean & Green Power Top 5: What are Renewable Resources? [Explained] | Renewable Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future | Clean & Green Power](https://pplrenewableenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/th-165-300x200.jpg)