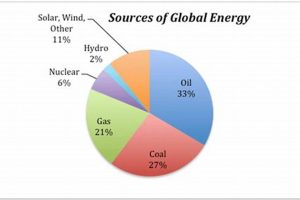

The question of whether atomic power can be classified alongside solar, wind, and hydropower necessitates a nuanced examination of its fuel source and sustainability. Unlike renewable resources that are naturally replenished, the generation of electricity through atomic fission relies on uranium, a finite resource extracted from the Earth.

The longevity of atomic power as a viable energy option is dependent on uranium reserves and advancements in reactor technology. While current uranium resources are estimated to last for several decades, the potential for breeder reactors, which produce more fissile material than they consume, could significantly extend the availability of atomic fuel. The initial investment and operational complexities, however, present considerable challenges.

The discourse surrounding atomic power often centers on its low carbon emissions during operation and its capacity to provide a stable baseload power supply. These attributes have led some to advocate for its inclusion in strategies aimed at mitigating climate change, despite the concerns regarding radioactive waste disposal and the potential for nuclear proliferation. The subsequent sections will delve into the key factors that differentiate atomic power from traditional renewable energy sources, assess its long-term sustainability, and evaluate its role in a future energy landscape.

Considerations Regarding Atomic Power Sustainability

The following points offer a framework for understanding the nuanced debate surrounding atomic energy and its classification relative to renewable sources.

Tip 1: Resource Depletion Awareness: Recognize that atomic power relies on uranium, a non-renewable resource extracted from the Earth. Current reserves are finite, and responsible usage necessitates strategies for resource optimization.

Tip 2: Evaluate Advanced Reactor Technologies: Research breeder reactor technologies, which can potentially extend the lifespan of atomic fuel by generating more fissile material than they consume. These technologies could reshape the long-term viability of atomic power.

Tip 3: Waste Management Solutions: Prioritize the development and implementation of safe and effective methods for the long-term storage and disposal of radioactive waste. Addressing this challenge is crucial for the environmental acceptability of atomic power.

Tip 4: Lifecycle Analysis Assessment: Conduct comprehensive lifecycle analyses to fully assess the environmental impacts of atomic power, encompassing uranium mining, reactor construction, operation, and decommissioning. This provides a holistic view beyond operational emissions.

Tip 5: Nuclear Proliferation Concerns: Remain vigilant regarding the potential for nuclear proliferation associated with atomic power technologies. Implement robust safeguards and international agreements to minimize this risk.

Tip 6: Economic Viability Analysis: Analyze the economic competitiveness of atomic power compared to other energy sources, considering factors such as capital costs, operating expenses, and fuel prices. This informs realistic energy planning.

Tip 7: Public Perception and Engagement: Foster open and transparent communication regarding the risks and benefits of atomic power to build public trust and informed decision-making. Address public concerns regarding safety and environmental impacts.

These considerations underscore the complexities involved in classifying atomic energy. A comprehensive approach requires balancing its low carbon emissions with resource limitations, waste management challenges, and proliferation concerns.

The concluding section will synthesize these points, offering a final perspective on the role of atomic power within a broader energy strategy.

1. Finite Uranium Supply

The reliance of atomic fission on uranium directly impacts the debate concerning atomic power’s status as a renewable energy source. Unlike solar, wind, or hydropower, which derive energy from perpetually replenished resources, atomic energy depends on a finite quantity of uranium extracted from the Earth’s crust. This fundamental distinction challenges its classification as a renewable resource. The depletion of accessible uranium reserves poses a direct threat to the long-term viability of atomic energy. Without sustained uranium extraction, atomic power generation is unsustainable.

The practical significance of this limitation manifests in several ways. Uranium mining operations carry their own environmental consequences, including habitat disruption and potential water contamination. Furthermore, the geographic concentration of uranium deposits introduces geopolitical considerations, potentially creating supply dependencies and price volatility. Example: Canada and Kazakhstan possess substantial uranium reserves and influence global supply and pricing.

Ultimately, the finite nature of uranium dictates that atomic power cannot be considered a renewable energy source in the conventional sense. While advancements in reactor technology, such as breeder reactors, aim to mitigate this limitation by producing more fissile material, they do not eliminate the fundamental dependence on a finite resource. Understanding this constraint is crucial for developing comprehensive and sustainable energy strategies that incorporate both renewable and non-renewable sources.

2. Waste Disposal Challenges

A critical factor distinguishing atomic power from renewable sources lies in the management of radioactive waste. Spent nuclear fuel and other radioactive materials produced during reactor operation pose a significant long-term environmental hazard. The necessity for secure, long-term storage solutions for this waste introduces a sustainability challenge fundamentally different from those associated with renewable energy technologies. The question of whether atomic power can be classified as “renewable” is directly impacted by the unresolved issue of safely isolating radioactive waste from the environment for thousands of years.

The absence of a universally accepted, permanent disposal solution underscores the gravity of this challenge. Current strategies often involve interim storage in on-site facilities, which are not designed for indefinite containment. The geological repository at Yucca Mountain in the United States, intended for long-term storage, has faced considerable political and technical obstacles, highlighting the difficulties in establishing such sites. Even if technological solutions advance, the potential for accidents, geological instability, or human intrusion at these repositories remains a concern. The Fukushima Daiichi accident serves as a stark reminder of the potential for unforeseen events to compromise the safe management of radioactive materials. The long-term environmental consequences of improperly managed waste are significant, including potential contamination of groundwater and ecosystems.

In conclusion, the waste disposal challenges associated with atomic power directly conflict with the principles of renewable energy sustainability. The need for long-term waste isolation and the potential environmental risks preclude atomic power from being classified as renewable in the same manner as solar, wind, or hydroelectric power. A comprehensive assessment of atomic energy’s sustainability must prioritize the development and implementation of safe and permanent waste disposal solutions.

3. Breeder Reactor Potential

The potential of breeder reactor technology to fundamentally alter the resource constraints of atomic power significantly impacts the discussion of whether atomic energy can be classified as a renewable source. These reactors, designed to produce more fissile material than they consume, offer a pathway to extending uranium fuel resources and potentially achieving a degree of fuel cycle self-sufficiency.

- Fuel Resource Extension

Breeder reactors enhance the utilization of uranium resources by converting non-fissile isotopes, such as uranium-238, into plutonium-239, which is fissile. This process dramatically increases the amount of energy that can be extracted from a given quantity of uranium. For instance, conventional reactors primarily utilize uranium-235, which comprises a small fraction of natural uranium, whereas breeder reactors can utilize the far more abundant uranium-238. This increased efficiency extends the lifespan of available uranium resources.

- Waste Reduction Possibilities

Advanced breeder reactor designs can potentially reduce the volume and radiotoxicity of long-lived radioactive waste. By transmuting certain long-lived isotopes into shorter-lived or stable elements, these reactors may offer a more sustainable approach to waste management than current methods. For example, certain breeder reactor designs aim to recycle actinides present in spent nuclear fuel, thereby reducing the long-term burden of radioactive waste disposal. However, this benefit is contingent upon the successful development and deployment of these advanced transmutation technologies.

- Technological and Economic Challenges

Despite their potential benefits, breeder reactors face significant technological and economic hurdles. The complexity of breeder reactor designs, including the use of liquid metal coolants like sodium, introduces engineering challenges and safety considerations. The high capital costs associated with constructing and operating breeder reactors also present a barrier to their widespread adoption. An example is the ongoing research and development efforts required to optimize breeder reactor performance and ensure their safe and reliable operation, including addressing concerns related to coolant reactivity and material compatibility.

- Proliferation Concerns

The use of plutonium in breeder reactors raises concerns regarding nuclear proliferation. Plutonium-239, produced in breeder reactors, can be used to construct nuclear weapons, increasing the risk of diversion or theft of nuclear materials. Robust safeguards and international oversight are essential to mitigate this risk. For example, strict international monitoring regimes are necessary to ensure that plutonium produced in breeder reactors is not diverted for weapons purposes and that breeder reactor technology is not misused to develop nuclear weapons capabilities.

The potential of breeder reactors to extend fuel resources and reduce waste raises the possibility of a more sustainable atomic energy future. However, the technological, economic, and proliferation challenges must be addressed before breeder reactors can significantly contribute to a more renewable-like energy supply. While not inherently renewable, breeder reactor technology offers the potential to reshape the resource landscape and redefine the long-term sustainability of atomic power, influencing its classification relative to renewable energy sources.

4. Carbon Emissions Profile

The carbon emissions profile of atomic power is a crucial element in evaluating whether it can be considered a renewable energy source. Unlike fossil fuel power plants, atomic facilities do not directly emit significant amounts of greenhouse gasses during electricity generation. This absence of direct emissions has led some to argue for its inclusion as a “clean” energy source, particularly in the context of mitigating climate change. The initial construction of atomic power plants and the mining and processing of uranium, however, do involve carbon emissions. These lifecycle emissions, though lower than those of coal or natural gas, necessitate a thorough assessment when comparing atomic power to truly renewable energy sources like wind and solar.

The importance of considering the entire lifecycle is illustrated by comparing atomic power to solar energy. While solar panels require significant energy for their manufacture, the operational phase is virtually carbon-free. Similarly, wind turbines have minimal operational emissions. The comparison highlights a fundamental difference: renewable energy sources rely on naturally replenishing resources and exhibit lower overall carbon footprints across their lifecycles. The extraction and processing of uranium, along with the construction of atomic power plants, require substantial energy inputs, often derived from fossil fuels. This contributes to a higher overall carbon footprint compared to the operational phase alone. Example: The construction of a typical atomic power plant requires the use of cement and steel, both of which are energy-intensive to produce, thus contributing to the plant’s lifecycle carbon emissions.

In conclusion, while the absence of direct greenhouse gas emissions during atomic power generation presents a clear advantage over fossil fuels, a comprehensive lifecycle assessment reveals that atomic power is not entirely carbon-free. The embedded carbon in uranium mining, processing, and plant construction differentiates it from truly renewable sources. Consequently, while atomic power can play a role in decarbonizing the energy sector, its carbon emissions profile prevents its classification as a renewable energy source.

5. Proliferation Risk Assessment

The evaluation of nuclear proliferation risk is intrinsically linked to the question of whether atomic energy can be categorized as a renewable source. The connection stems from the fuel cycle and the potential for diversion of nuclear materials for weapons purposes. While the “renewability” debate centers on resource availability and waste management, proliferation risk introduces a security dimension that directly affects the long-term sustainability and acceptability of atomic power. If the global expansion of atomic energy increases the risk of nuclear weapons proliferation, the viability and social license for atomic power generation are fundamentally undermined, regardless of advancements in reactor technology or uranium resource management.

The proliferation risk assessment considers factors such as the security of nuclear facilities, the transportation of nuclear materials, and the potential for states or non-state actors to acquire the technology and materials needed to produce nuclear weapons. The use of plutonium, a byproduct of atomic reactor operation and a key ingredient in nuclear weapons, is a central concern. For example, the A.Q. Khan network demonstrated the ease with which nuclear technology and materials can be proliferated, highlighting the vulnerability of the atomic fuel cycle. A robust proliferation risk assessment includes measures such as international safeguards, physical security upgrades, and the development of proliferation-resistant reactor designs. The absence of effective safeguards increases the likelihood of diversion, which, in turn, jeopardizes the responsible and sustainable utilization of atomic power.

In conclusion, while the “renewability” of atomic power is debated based on resource constraints and waste disposal, the proliferation risk assessment adds a critical security layer. Failure to effectively manage and mitigate this risk negates any potential benefits derived from atomic power, regardless of its carbon emissions profile or uranium resource availability. A secure and proliferation-resistant atomic energy system is a prerequisite for its long-term viability and social acceptance, thereby making proliferation risk assessment a vital component of the broader assessment of whether atomic energy can be a sustainable energy source.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following questions address common inquiries concerning the classification of atomic power and its status relative to renewable energy resources. The answers provided aim to offer clarity on key issues surrounding the debate.

Question 1: Does the absence of direct carbon emissions during electricity generation qualify atomic energy as renewable?

No. While atomic facilities do not directly emit greenhouse gasses during operation, the extraction and processing of uranium fuel, as well as the construction of atomic power plants, do generate carbon emissions. A comprehensive lifecycle analysis reveals that atomic energy is not entirely carbon-free, differentiating it from renewable sources.

Question 2: How does the finite supply of uranium impact the classification of atomic energy?

Atomic power relies on uranium, a non-renewable resource extracted from the Earth. The finite nature of uranium dictates that atomic power cannot be considered a renewable energy source in the conventional sense. This contrasts with renewable sources that are naturally replenished.

Question 3: What role do breeder reactors play in the debate about atomic energy’s renewability?

Breeder reactors, which produce more fissile material than they consume, offer a pathway to extending uranium fuel resources. However, technological and economic challenges, along with proliferation concerns, must be addressed before breeder reactors can significantly contribute to a more renewable-like energy supply.

Question 4: What are the key concerns regarding radioactive waste disposal?

Spent atomic fuel and other radioactive materials produced during reactor operation pose a significant long-term environmental hazard. The necessity for secure, long-term storage solutions for this waste introduces a sustainability challenge fundamentally different from those associated with renewable energy technologies.

Question 5: How does the risk of nuclear proliferation influence the assessment of atomic energy’s sustainability?

The potential for diversion of nuclear materials for weapons purposes introduces a security dimension that directly affects the long-term viability and acceptability of atomic power. If the global expansion of atomic energy increases the risk of nuclear weapons proliferation, the social license for atomic power generation is undermined.

Question 6: Can technological advancements in atomic power generation ultimately lead to a renewable classification?

While advancements in reactor technology, such as breeder reactors and advanced waste treatment methods, may improve the sustainability of atomic power, the fundamental reliance on a finite resource and the challenges associated with radioactive waste disposal prevent its classification as a renewable energy source.

The preceding responses highlight the complex factors involved in classifying atomic energy. While atomic power offers advantages such as low carbon emissions during operation, its reliance on a finite resource, the challenge of waste disposal, and proliferation risks preclude its classification as renewable.

The subsequent section will provide a concluding analysis, synthesizing the key points discussed and offering a final perspective on atomic power’s role in the future energy landscape.

Conclusion

This exploration has systematically examined the multifaceted question of whether atomic energy qualifies as a renewable source. While atomic power offers certain advantages, such as low carbon emissions during electricity generation, fundamental limitations preclude its classification alongside truly renewable resources like solar, wind, and hydropower. These limitations include the reliance on a finite uranium supply, the challenges associated with radioactive waste disposal, and the risks of nuclear proliferation.

The ongoing debate surrounding atomic energy’s role in the future energy mix necessitates a balanced and informed perspective. While atomic power can contribute to decarbonization efforts, its inherent constraints must be carefully weighed against the potential benefits and risks. Further research and development into advanced reactor technologies and waste management solutions are essential. However, a truly sustainable energy future requires a diversified approach, prioritizing the continued development and deployment of genuinely renewable energy sources.

![Basics: What is an Energy Source? [Explained] Renewable Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future | Clean & Green Power Basics: What is an Energy Source? [Explained] | Renewable Energy Solutions for a Sustainable Future | Clean & Green Power](https://pplrenewableenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/th-100-300x200.jpg)