The question of whether a specific fossil fuel can be classified as a sustainable power alternative is a subject of ongoing debate. This query typically centers on whether the resource is replenished at a rate comparable to its consumption. Conventional understanding suggests that sources formed over millions of years are finite and therefore not sustainable in the long term.

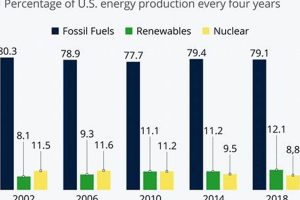

The significance of energy sources in modern society cannot be overstated, underpinning industrial activity, transportation, and residential comfort. Historically, the reliance on particular resources has driven technological advancements and shaped geopolitical landscapes. The shift towards cleaner energy is increasingly prioritized in response to growing environmental concerns and the need for long-term energy security.

The subsequent discussion will delve into the specific characteristics of this resource, contrasting its formation process and environmental impact with those of demonstrably renewable options like solar, wind, and geothermal power. This analysis aims to clarify the position of this resource within the broader context of sustainable energy strategies and future energy planning.

Insights Regarding the Classification of a Specific Fossil Fuel

This section provides key insights for understanding the debated classification of a specific geological deposit as a sustainable energy alternative. These points address common misconceptions and offer a more nuanced perspective.

Tip 1: Distinguish Between Formation Rate and Consumption Rate: The critical factor is whether the rate at which this resource forms aligns with, or exceeds, the rate at which it is extracted and consumed. Due to its creation over geological timescales, the extraction rate far surpasses the replenishment rate.

Tip 2: Understand the Carbon Cycle Implications: The combustion of this resource releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, a key contributor to climate change. While some carbon capture technologies exist, their widespread implementation remains a challenge.

Tip 3: Consider the Methane Leakage Factor: Methane, the primary component of this resource, is a potent greenhouse gas. Leakage during extraction, transportation, and distribution can offset some of the climate benefits compared to other fossil fuels.

Tip 4: Evaluate the Resource’s Role as a Transition Fuel: The resource is often proposed as a bridge to a fully renewable energy future. Assess whether its use genuinely accelerates the transition or merely prolongs reliance on fossil fuels.

Tip 5: Analyze Life Cycle Assessments: Evaluate comprehensive life cycle assessments that account for all environmental impacts, from extraction to combustion, including water usage, land disturbance, and emissions of pollutants.

Tip 6: Compare with Truly Renewable Sources: Contrast the environmental impact and sustainability of this resource with demonstrably renewable energy sources like solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal, which are replenished naturally and have significantly lower carbon footprints.

Tip 7: Investigate Technological Advancements: Stay informed about technological advancements in carbon capture, methane leak detection and prevention, and alternative uses of this resource that could potentially mitigate its environmental impact.

Understanding these nuances is crucial for informed decision-making regarding energy policy, investment strategies, and individual consumption choices. A comprehensive approach that considers both the short-term benefits and long-term consequences is essential.

The final section will draw conclusions based on the above considerations and offer a perspective on the future role of this energy resource within the context of evolving energy landscapes.

1. Fossil Fuel (noun)

The term “fossil fuel” is central to understanding the debate surrounding the classification of natural gas as a renewable energy source. As a geological deposit formed from the remains of ancient organic matter, its inherent properties as a finite and non-renewable resource influence this discussion profoundly.

- Origin and Formation of Natural Gas

Natural gas originates from the decomposition of prehistoric plant and animal matter over millions of years, subjected to immense pressure and heat beneath the Earth’s surface. This lengthy formation process directly contradicts the concept of renewability, as the rate of formation is infinitesimal compared to the rate of human consumption.

- Composition and Combustion

Natural gas primarily consists of methane (CH4), and its combustion produces carbon dioxide (CO2), a significant greenhouse gas. The release of stored carbon into the atmosphere contributes to global warming and climate change. This environmental impact contrasts sharply with the characteristics of renewable energy sources, which aim to minimize or eliminate carbon emissions.

- Depletion and Resource Scarcity

Fossil fuels, including natural gas, are finite resources subject to depletion. Continued extraction and consumption will inevitably lead to resource scarcity and increased costs. Renewable energy sources, on the other hand, are replenished naturally, offering a more sustainable long-term solution to energy needs.

- Environmental Impact of Extraction and Transportation

The extraction and transportation of natural gas can have significant environmental consequences, including habitat destruction, water contamination, and methane leakage. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, and even small leaks can significantly offset the climate benefits compared to other fossil fuels. Renewable energy sources generally have a smaller environmental footprint in terms of land use, water consumption, and pollution.

Considering these aspects of “fossil fuel” its geological origin, carbon emissions from combustion, finite nature, and environmental impact during extraction it becomes evident that categorizing natural gas as a renewable energy source is fundamentally inaccurate. This underscores the importance of distinguishing between finite fossil resources and truly renewable energy alternatives when formulating sustainable energy policies and strategies.

2. Finite Resource (noun)

The designation of natural gas as a finite resource is a central determinant in the debate surrounding its classification as a renewable energy source. A finite resource, by definition, exists in limited quantities and is not replenished at a rate comparable to its consumption. This characteristic directly contradicts the defining feature of renewable energy, which is its ability to be naturally replenished within a human timescale.

The geological processes responsible for the formation of natural gas occurred over millions of years. Organic matter, buried under layers of sediment and subjected to intense heat and pressure, transformed into hydrocarbon deposits. The extraction of natural gas from these deposits occurs at a rate vastly exceeding the natural rate of formation. Therefore, while natural gas may be abundant in certain regions, its overall supply is ultimately constrained by the finite amount formed over geological epochs. This limitation has direct implications for energy security, economic stability, and the long-term sustainability of relying on natural gas as a primary energy source. For example, geopolitical tensions surrounding regions rich in natural gas deposits underscore the importance of diversifying energy portfolios and transitioning to truly renewable alternatives. Similarly, the price volatility of natural gas, influenced by supply constraints and geopolitical factors, affects energy consumers and businesses alike.

In conclusion, the concept of natural gas as a finite resource fundamentally undermines its classification as a renewable energy source. Recognizing this distinction is crucial for informed energy policy development, investment decisions, and individual consumption choices. The inherent limitations of natural gas necessitate a strategic shift towards truly renewable energy sources to ensure long-term energy security and environmental sustainability. Challenges remain in scaling up renewable energy infrastructure and addressing intermittency issues. However, these challenges are outweighed by the imperative to transition away from finite fossil fuels and embrace a future powered by sustainable resources.

3. Carbon Emissions (noun)

Carbon emissions are intrinsically linked to the classification of a specific geological deposit as a renewable energy source. The combustion of this resource, primarily methane, releases carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere. This release of stored carbon, accumulated over millions of years, is a primary contributor to the greenhouse effect and subsequent climate change. The volume of carbon released during the utilization of this resource directly impacts its standing as a potential sustainable alternative. For instance, power plants utilizing this resource, while often cleaner burning than coal, still generate significant carbon dioxide emissions, affecting global climate models and international emissions reduction targets. The existence of substantial carbon emissions associated with its use inherently contradicts the criteria for renewable energy sources, which ideally have minimal or zero net carbon emissions.

Quantifying the carbon footprint of this resource requires consideration of the entire lifecycle, including extraction, processing, transportation, and combustion. Activities such as hydraulic fracturing and pipeline transport can release methane, a potent greenhouse gas, further exacerbating the environmental impact. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies offer a potential avenue for mitigating emissions from power plants using this resource. However, the widespread adoption of CCS faces technological and economic hurdles. Furthermore, even with CCS implementation, the energy required to power these systems can reduce their overall effectiveness. An example of this complexity is the Gorgon Project in Australia, where CCS implementation has faced challenges in meeting its intended emissions reduction goals. This indicates that while CCS can play a role, it is not a complete solution for offsetting the carbon emissions associated with the resource. Other sources of carbon emissions include the creation of leaks in pipelines.

In summary, the significant carbon emissions associated with the extraction, processing, transportation, and combustion of the specific resource directly disqualify it from being classified as a renewable energy source. While technological advancements like CCS offer potential mitigation strategies, they are not without their limitations and challenges. The ongoing debate highlights the critical need to transition towards energy sources with minimal or no carbon emissions to address climate change effectively. The environmental consequences of carbon emissions underscore the importance of embracing truly renewable alternatives such as solar, wind, and geothermal energy to achieve a sustainable energy future. The discussion of sustainable energy is incomplete with the carbon capture and utilization discussion.

4. Methane Leakage (noun)

The escape of methane, the primary component of natural gas, into the atmosphere, termed “methane leakage,” presents a significant obstacle to classifying this resource as a renewable energy source. Methane’s potency as a greenhouse gas, far exceeding that of carbon dioxide over shorter time horizons, necessitates a comprehensive understanding of leakage sources and their environmental consequences.

- Sources of Methane Leakage

Methane leakage occurs across the entire natural gas supply chain, from extraction at well sites to processing facilities, pipelines, and distribution networks. Unintentional releases arise from equipment malfunctions, aging infrastructure, and inadequate monitoring systems. Intentional venting, a controlled release of methane for operational safety or maintenance purposes, also contributes to overall leakage rates. Studies have identified specific areas with high leakage rates, such as regions with older pipelines or poorly maintained extraction infrastructure. The cumulative effect of these leaks substantially diminishes the potential climate benefits compared to other fossil fuels and directly contradicts the low-emission profile associated with renewable energy sources.

- Global Warming Potential of Methane

Methane’s global warming potential (GWP) is significantly higher than that of carbon dioxide, particularly over a 20-year timeframe. This means that even small amounts of methane leakage can have a disproportionately large impact on climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) provides updated GWP values, highlighting the urgency of mitigating methane emissions. This high GWP underscores that while natural gas combustion produces less CO2 than coal combustion, the benefit is potentially negated by even modest amounts of methane leakage. If a significant percentage is leaked, methane becomes a bigger polluter.

- Detection and Mitigation Technologies

Various technologies are available for detecting and mitigating methane leakage. Aerial surveys using infrared cameras can identify large leaks over wide areas. Ground-based sensors can pinpoint smaller leaks in pipelines and equipment. Mitigation strategies include upgrading infrastructure, implementing leak detection and repair programs, and capturing methane from venting operations. However, the widespread adoption of these technologies faces economic and regulatory barriers. For instance, the cost of retrofitting older pipelines can be substantial, and regulations mandating leak detection and repair vary significantly across regions. If there is not enough investment into new tech, methane will be a persistent pollutant.

- Impact on Life Cycle Assessments

Methane leakage significantly affects the life cycle assessment (LCA) of natural gas. LCAs analyze the environmental impacts of a product or service throughout its entire life cycle, from resource extraction to end-of-life disposal. Incorporating methane leakage into LCAs reveals a more accurate picture of the total greenhouse gas emissions associated with natural gas. A higher leakage rate diminishes the perceived environmental benefits of utilizing natural gas compared to coal or oil. When methane leakage estimates are low, it is more likely that people support natural gas because it is a more economic energy source. However, if the leakage rate increases, support decreases. This also undermines its viability as a low-carbon bridge fuel in the transition to a renewable energy economy.

The cumulative effect of methane leakage, from extraction to distribution, presents a substantial challenge to the sustainability of natural gas as an energy source. The high global warming potential of methane, coupled with the economic and regulatory barriers to effective leak detection and mitigation, highlights the need for a critical reassessment of its role in a low-carbon energy future. As a result, “methane leakage” significantly impacts whether “is natural gas renewable energy source” is a classification that can be supported environmentally or scientifically.

5. Depletion Rate (noun)

The “depletion rate” of natural gas, defined as the speed at which reserves are exhausted relative to their replenishment, is a critical factor in determining whether its classification as a renewable energy source is justifiable. A resource with a high depletion rate and negligible replenishment cannot be considered renewable, regardless of other potential environmental benefits it may offer.

- Extraction vs. Formation Rate

Natural gas forms over millions of years through geological processes, transforming organic matter into hydrocarbons. However, the rate at which humans extract natural gas far exceeds its natural formation rate. This imbalance leads to a net decrease in available reserves, characteristic of a non-renewable resource. For example, the rapid growth in shale gas extraction in the United States significantly increased natural gas production but also accelerated the depletion of these reserves.

- Reserve Estimates and Projections

Estimates of remaining natural gas reserves are essential for projecting future availability and depletion rates. These estimates, however, are subject to uncertainty due to technological advancements in extraction and the discovery of new reserves. Even with optimistic reserve projections, the finite nature of natural gas means that its depletion is inevitable. The British Petroleum (BP) Statistical Review of World Energy provides annual data on global natural gas reserves and production, offering insights into the changing landscape of resource availability. Any projection of a depleting resource, even with new technological advances, cannot meet renewable classification.

- Economic Implications of Depletion

As natural gas reserves deplete, the cost of extraction typically increases, potentially leading to higher energy prices. This economic impact can affect industries reliant on natural gas, such as power generation, manufacturing, and heating. Resource depletion also incentivizes the development of alternative energy sources, including renewable options. Regions with dwindling natural gas reserves may face economic challenges if they fail to diversify their energy portfolio and transition to more sustainable solutions. For instance, energy-intensive industries require an accessible resource base.

- Environmental Consequences of Depletion

The pursuit of increasingly difficult-to-access natural gas reserves can lead to greater environmental damage. Unconventional extraction methods, such as hydraulic fracturing, may have significant environmental consequences, including water contamination and habitat disruption. As easily accessible reserves are depleted, there is an increased incentive to exploit environmentally sensitive areas, further exacerbating these impacts. Environmental consequences of depletion would make it harder to be classified as a renewable energy source.

Considering the high depletion rate of natural gas relative to its formation, it cannot be classified as a renewable energy source. While technological advancements may extend the lifespan of natural gas reserves and improve extraction efficiency, the fundamental issue remains: natural gas is a finite resource subject to depletion. Therefore, sustainable energy policies must prioritize the development and deployment of truly renewable energy sources to ensure long-term energy security and environmental sustainability.

6. Transition Fuel (noun)

The concept of “transition fuel” is frequently invoked in discussions surrounding energy policy and the move away from high-carbon fossil fuels. The designation of a particular energy source as a transition fuel implies its temporary use to bridge the gap between current reliance on carbon-intensive energy and a future dominated by renewable and sustainable sources. Natural gas is often proposed as such a fuel, predicated on the assumption that it produces lower carbon emissions than coal when burned for electricity generation. However, the validity of this assumption and the overall role of natural gas in facilitating a genuine transition to renewable energy are subjects of ongoing debate. The debate arises from comparing the CO2 produced by each source, not from methane leakage or carbon emissions during the creation of the energy source.

The purported benefits of this fuel as a transitional source hinge on several factors. First, its combustion must demonstrably produce significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions than the energy source it replaces. Second, its deployment must not impede the growth and adoption of renewable energy technologies. Third, infrastructure investments in the energy source should be compatible with a long-term sustainable energy system. Failing these tests undermines the rationale for designating it a transition fuel. For instance, constructing new natural gas pipelines with a lifespan of several decades risks creating a stranded asset problem if renewable energy sources become economically competitive more rapidly than anticipated. This can lead to a continuation of using natural gas for longer than is desired.

Ultimately, the justification for using natural gas as a transition fuel depends on its ability to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy sources and reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions in the short to medium term. However, its classification as a renewable energy source is not scientifically accurate. A critical assessment requires a holistic approach, considering not only direct combustion emissions but also methane leakage throughout the supply chain and the potential for long-term infrastructure lock-in. Clear targets and policies are needed to ensure it serves as a genuine bridge and not a detour on the path to a sustainable energy future, and should not be confused as renewable.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the classification of natural gas as a renewable energy source, providing clear and concise answers based on scientific principles and industry data.

Question 1: Is natural gas a renewable resource?

No. Natural gas is a fossil fuel formed over millions of years from the remains of ancient organisms. Its formation rate is negligible compared to its extraction rate, making it a finite and non-renewable resource.

Question 2: Does natural gas produce fewer carbon emissions than other fossil fuels?

While natural gas combustion generally produces less carbon dioxide than coal combustion, methane leakage during extraction and transportation can offset this benefit. The overall greenhouse gas impact depends on the leakage rate and the time horizon considered.

Question 3: Can carbon capture and storage (CCS) make natural gas a renewable energy source?

CCS technologies can reduce carbon dioxide emissions from natural gas power plants, but they do not address methane leakage or the fundamental issue of its finite nature. CCS is also energy-intensive and faces technological and economic challenges.

Question 4: Is natural gas a “transition fuel” to a renewable energy future?

Natural gas is sometimes proposed as a transition fuel, but its suitability depends on whether it accelerates the deployment of renewable energy and reduces overall greenhouse gas emissions. Infrastructure investments in natural gas must be compatible with a long-term sustainable energy system.

Question 5: What are the primary environmental impacts of natural gas extraction and transportation?

Environmental impacts include habitat destruction, water contamination, and methane leakage. Hydraulic fracturing, a common extraction method, can have significant environmental consequences.

Question 6: How do renewable energy sources differ from natural gas?

Renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal, are replenished naturally and have minimal or zero net carbon emissions. They offer a more sustainable long-term solution to energy needs than natural gas.

In summary, natural gas possesses characteristics inconsistent with renewable energy sources. Its finite nature, carbon emissions, and potential for methane leakage preclude its classification as renewable. Renewable alternatives represent more sustainable and environmentally sound options.

The next section provides conclusive remarks and future outlook concerning the topic.

Conclusion

This article explored the premise of “is natural gas renewable energy source” by examining its formation, environmental impact, and depletion rate. The analysis revealed that natural gas, a fossil fuel derived from geological processes spanning millions of years, cannot be considered renewable. Its extraction and combustion contribute to carbon emissions and methane leakage, exacerbating climate change. The finite nature of natural gas, coupled with its rapid depletion rate, further disqualifies it from renewable status.

Given the pressing need for sustainable energy solutions, a clear distinction between fossil fuels and renewable resources is crucial. While natural gas may serve as a transitional energy source in certain contexts, its long-term viability is limited by its environmental impact and finite reserves. Therefore, continued prioritization of truly renewable energy sources is essential for ensuring a sustainable and environmentally responsible energy future.