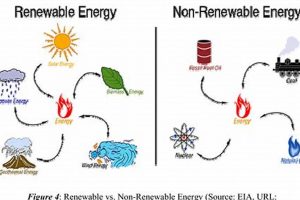

These finite energy sources are characterized by their inability to be replenished within a human lifespan. They exist in limited quantities, having been formed over millions of years. Common examples include fossil fuels such as coal, petroleum (crude oil), and natural gas, as well as nuclear fuels like uranium.

Their significance lies in their historical role as primary drivers of industrialization and economic development. These sources have powered societies for centuries, enabling transportation, manufacturing, and electricity generation on a massive scale. However, their extraction and utilization pose environmental challenges, including greenhouse gas emissions, air and water pollution, and habitat destruction. The concentrated energy they provide has been instrumental in shaping modern civilization, but their depletion necessitates the exploration and adoption of alternative energy strategies.

The following sections will delve into the specifics of each major category of these resources, analyzing their formation, extraction methods, environmental impacts, and the ongoing efforts to transition towards more sustainable alternatives. A comprehensive understanding of these aspects is crucial for informed decision-making regarding energy policy and future technological advancements.

Strategies for Responsible Consumption of Finite Energy Sources

The responsible management of dwindling reserves necessitates a multi-faceted approach encompassing conservation, efficiency improvements, and strategic diversification.

Tip 1: Prioritize Energy Conservation: Implementing energy-saving measures in residential, commercial, and industrial settings can significantly reduce overall demand. Examples include optimizing building insulation, utilizing energy-efficient appliances, and promoting behavioral changes that minimize energy waste.

Tip 2: Enhance Energy Efficiency: Investing in technologies and infrastructure that maximize energy output while minimizing input is crucial. This includes upgrading power grids, employing advanced combustion technologies in power plants, and developing more efficient transportation systems.

Tip 3: Reduce Reliance on Fossil Fuels for Transportation: Transitioning to alternative transportation methods such as electric vehicles, public transportation, and cycling can decrease dependence on petroleum-based fuels.

Tip 4: Implement Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) Technologies: Developing and deploying CCS technologies at power plants and industrial facilities can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions by capturing carbon dioxide and storing it underground.

Tip 5: Promote Waste Heat Recovery: Capturing and reusing waste heat from industrial processes and power generation can improve overall energy efficiency and reduce the need for additional fuel consumption.

Tip 6: Invest in Research and Development of Alternative Technologies: Funding research into advanced nuclear technologies, such as thorium reactors, and other potential energy sources can provide long-term solutions to energy security.

Tip 7: Support Policies That Encourage Sustainable Energy Practices: Advocating for policies that incentivize energy conservation, efficiency improvements, and the development of renewable energy sources can create a more sustainable energy future.

Implementing these strategies can extend the availability of existing reserves, mitigate environmental impacts, and foster a more sustainable energy future. A comprehensive approach, combining technological advancements with policy interventions and behavioral changes, is essential for navigating the energy challenges ahead.

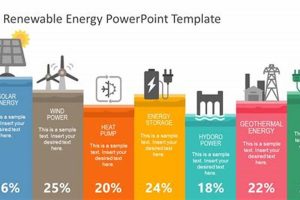

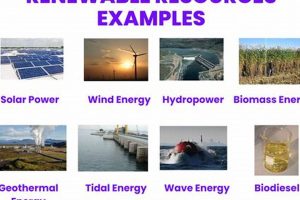

The subsequent sections will elaborate on the alternative energy sources that can replace these resources, exploring their potential, limitations, and the infrastructure required for their widespread adoption.

1. Depletion

The term “depletion” is intrinsically linked to the concept of finite energy sources. Depletion refers to the exhaustion or consumption of these resources at a rate that exceeds their natural rate of formation. Since these resources exist in fixed quantities, their extraction inevitably leads to a reduction in the available reserves. The faster these sources are utilized, the more rapidly their depletion occurs, creating a scenario where future availability becomes increasingly uncertain. For example, the ongoing extraction of crude oil from reserves worldwide is steadily diminishing the total global oil supply. This dwindling supply is a direct consequence of the rate of consumption far surpassing the geological processes that created the oil over millions of years.

The understanding of depletion is vital for resource management and energy policy. A clear grasp of the depletion rate allows for more accurate forecasting of future supply and potential price fluctuations. These projections can inform decisions regarding energy infrastructure investments, the development of alternative energy sources, and conservation measures aimed at extending the lifespan of existing reserves. Moreover, depletion awareness can drive innovation in extraction technologies, as seen in the development of enhanced oil recovery methods to access previously inaccessible resources, albeit at a higher cost and with potentially greater environmental impact. Similarly, depletion concerns prompted the exploration of unconventional sources, such as shale gas, which, while expanding the resource base, raise environmental and sustainability questions.

In summary, depletion is a fundamental characteristic of finite energy sources, dictating their long-term availability and influencing energy strategies. Addressing the challenges posed by depletion requires a proactive approach, combining responsible resource management, technological innovation, and a transition to sustainable energy alternatives. Failure to acknowledge and respond to the reality of depletion will inevitably lead to energy scarcity, economic instability, and increased geopolitical tensions.

2. Environmental Impact

The utilization of finite energy sources is inextricably linked to a range of environmental consequences. These impacts, varying in scale and severity, are a critical consideration in the ongoing debate regarding energy policy and sustainability. They directly affect ecosystems, human health, and the global climate.

- Air Pollution

Combustion of fossil fuels releases pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, and carbon monoxide into the atmosphere. These pollutants contribute to smog, acid rain, and respiratory illnesses. For example, coal-fired power plants are a significant source of sulfur dioxide, which contributes to acid rain that damages forests and aquatic ecosystems. Air pollution from vehicles, primarily fueled by petroleum, exacerbates urban smog and contributes to respiratory ailments.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The burning of fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide, a primary greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming and climate change. Methane, another potent greenhouse gas, is released during the extraction and transportation of natural gas. Rising global temperatures lead to a cascade of effects, including sea-level rise, changes in precipitation patterns, increased frequency of extreme weather events, and disruptions to ecosystems.

- Water Pollution

The extraction and processing of these resources can contaminate water sources. Oil spills, such as the Deepwater Horizon disaster, have devastating effects on marine life and coastal ecosystems. Fracking, a method used to extract natural gas, can contaminate groundwater with chemicals and methane. Coal mining can lead to acid mine drainage, polluting rivers and streams with heavy metals.

- Habitat Destruction

The extraction of fossil fuels and uranium often requires large-scale land disturbance, leading to habitat destruction and loss of biodiversity. Mountaintop removal coal mining, for instance, obliterates entire ecosystems. Pipeline construction and oil drilling disrupt natural habitats and can fragment wildlife populations.

These environmental consequences underscore the need for a transition to alternative energy sources and the implementation of mitigation strategies. The long-term sustainability of energy systems hinges on minimizing the adverse effects associated with resource extraction and utilization, ensuring the health of the planet for future generations.

3. Fossil Fuel Formation

The formation of fossil fuels is a geological process occurring over millions of years, directly resulting in the creation of significant sources categorized as non-renewable energy. This protracted genesis begins with the accumulation of organic matter, primarily the remains of dead plants and animals, in sedimentary environments such as swamps and marine basins. Anaerobic conditions, characterized by a lack of oxygen, impede complete decomposition, allowing the organic material to accumulate and form peat or organic-rich mud. As subsequent layers of sediment accumulate, increasing pressure and temperature transform the organic matter into coal, oil, or natural gas. The specific type of fossil fuel produced depends on the original organic material, the temperature and pressure conditions, and the presence of catalysts. For instance, coal formation occurs from terrestrial plant matter in swamps, while oil and natural gas originate from marine organisms buried in ocean sediments. The gradual transformation involves a series of chemical reactions that break down complex organic molecules into simpler, energy-rich compounds.

The understanding of fossil fuel formation is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, it explains why these resources are finite. Given the immense timescales involved, the rate of formation is negligible compared to the rate of current extraction and consumption. Secondly, it aids in resource exploration and assessment. Knowledge of the geological conditions conducive to fossil fuel formation allows geologists to identify potential deposits and estimate the size of reserves. For example, the presence of ancient sedimentary basins with thick layers of organic-rich shale is a key indicator of potential oil and gas reserves. Thirdly, it informs discussions about the environmental impacts of fossil fuel use. The carbon stored in these fuels was originally sequestered from the atmosphere by plants through photosynthesis. Burning these fuels releases this stored carbon back into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. The formation process itself also involves the release of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, which can escape from coal seams and natural gas deposits.

In conclusion, the geological history of fossil fuel formation dictates their status as non-renewable resources. This protracted process, spanning millions of years, highlights the inherent limitations of these energy sources and underscores the imperative for developing sustainable energy alternatives. A comprehensive understanding of the formation process is essential for informed resource management, environmental impact assessment, and the transition to a low-carbon energy future.

4. Geopolitical Influence

The distribution of finite energy sources significantly shapes geopolitical dynamics, influencing international relations, economic stability, and national security strategies. Control over these resources translates to considerable influence on the global stage, creating both opportunities and vulnerabilities for nations.

- Resource Control and Power Projection

Nations possessing substantial reserves wield significant economic and political power. Control over key resources allows them to influence global energy markets, impacting prices and availability. This influence can be used to exert pressure on other nations, negotiate favorable trade agreements, or support strategic alliances. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), for example, demonstrates the collective influence of nations coordinating oil production policies.

- Energy Security and Strategic Alliances

Nations lacking sufficient energy resources are often dependent on imports, making them vulnerable to supply disruptions and price volatility. To mitigate these risks, they form strategic alliances with resource-rich countries, creating complex geopolitical relationships. These alliances can involve military cooperation, economic aid, and diplomatic support, shaping regional power dynamics and international security arrangements. The relationship between European nations and Russia regarding natural gas supply exemplifies this dynamic.

- Resource Competition and Conflict

Competition for access to limited energy resources can lead to tensions and conflicts between nations. Disputes over territorial boundaries, maritime rights, and pipeline routes are often intertwined with the desire to secure control over valuable resources. The South China Sea dispute, involving overlapping claims to oil and gas reserves, illustrates the potential for resource competition to escalate into geopolitical conflict.

- Economic Leverage and Sanctions

Nations can use their control over energy resources as a tool of economic leverage, imposing sanctions or restricting supply to achieve political objectives. These actions can have significant economic consequences for both the target nation and the global economy. The use of energy sanctions against Iran, for example, has aimed to curb its nuclear program and influence its foreign policy.

The geopolitical influence associated with finite energy sources underscores the importance of diversifying energy supplies and promoting sustainable energy alternatives. Reducing dependence on specific resources and nations can mitigate geopolitical risks and foster a more stable and equitable international order. Furthermore, the pursuit of renewable energy sources can enhance energy security and reduce the potential for resource-driven conflicts.

5. Limited reserves

The concept of “limited reserves” is fundamental to understanding the challenges and implications associated with non-renewable energy resources. These resources, by their very nature, exist in finite quantities, posing significant long-term constraints on their availability and utilization.

- Finite Supply

Non-renewable energy sources, such as fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) and uranium, are characterized by a fixed amount present on Earth. Their formation occurred over millions of years, and their rate of replenishment is negligible compared to the current rate of consumption. This finite supply directly limits the duration for which these resources can sustain global energy demands. For instance, estimates of remaining recoverable oil reserves suggest a finite timeframe for continued use, prompting concerns about peak oil and the need for alternative energy solutions.

- Uneven Distribution

The global distribution of non-renewable energy reserves is highly uneven. Certain regions possess abundant reserves of oil, natural gas, or coal, while others have limited or no access to these resources. This uneven distribution creates geopolitical dependencies and can lead to economic disparities and international tensions. For example, countries heavily reliant on imported oil are vulnerable to price fluctuations and supply disruptions, highlighting the strategic importance of resource control and diversification.

- Extraction Costs and Technological Limits

As readily accessible reserves are depleted, the extraction of remaining resources often becomes more challenging and expensive. This may involve tapping into deeper or more remote deposits, employing more complex extraction techniques, or processing lower-grade ores. The rising costs associated with extracting dwindling reserves can impact energy prices and economic competitiveness. Technological advancements can push back the physical limits of extraction, but economic and environmental constraints ultimately limit the extent to which these resources can be accessed.

- Peak Production and Decline

The phenomenon of “peak production” refers to the point at which the rate of extraction of a non-renewable resource reaches its maximum, after which production inevitably declines. While predicting the exact timing of peak production is challenging, the underlying principle remains valid: the exploitation of finite resources follows a trajectory of initial growth, followed by a peak, and then a gradual decline. This decline necessitates planning for alternative energy sources to mitigate the impact on energy supply and economic stability. The concept of peak oil, for example, has prompted significant research into renewable energy technologies and energy efficiency measures.

The limited nature of these reserves underscores the urgent need for sustainable energy practices and the development of renewable energy alternatives. As these resources dwindle, the focus must shift towards responsible resource management, technological innovation, and a transition to a diversified energy portfolio to ensure long-term energy security and environmental sustainability. Neglecting the reality of limited reserves can lead to economic instability, environmental degradation, and geopolitical tensions.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following questions and answers address common concerns and misconceptions regarding energy sources that are non-renewable.

Question 1: What defines energy sources as non-renewable?

Energy resources are designated as non-renewable due to their finite supply and the exceedingly long timescales required for their natural replenishment. The rate of consumption far exceeds any natural regeneration, effectively depleting reserves over time.

Question 2: What are the primary examples of non-renewable energy resources?

The primary examples encompass fossil fuels, including coal, petroleum (crude oil), and natural gas. Nuclear fuels, such as uranium, also fall under this category.

Question 3: What are the major environmental consequences associated with utilizing energy sources that are non-renewable?

The environmental consequences are multifaceted and include greenhouse gas emissions, air and water pollution, habitat destruction, and the potential for ecosystem disruption. These impacts contribute to climate change, respiratory illnesses, and loss of biodiversity.

Question 4: How does the uneven global distribution of non-renewable energy resources influence international relations?

The uneven distribution leads to geopolitical dependencies, resource competition, and the potential for conflict. Nations with substantial reserves wield significant economic and political power, while those lacking resources are vulnerable to supply disruptions and price volatility.

Question 5: What is meant by the term “peak production” in the context of non-renewable energy resources?

“Peak production” refers to the point at which the rate of extraction of a non-renewable resource reaches its maximum, after which production inevitably declines. This decline necessitates the development and adoption of alternative energy sources.

Question 6: What strategies can be implemented to mitigate the depletion of non-renewable energy resources?

Mitigation strategies include prioritizing energy conservation, enhancing energy efficiency, diversifying energy sources, implementing carbon capture and storage technologies, and promoting policies that encourage sustainable energy practices.

These responses provide a foundational understanding of the critical issues surrounding energy sources that are non-renewable.

The following sections will further explore the alternative energy resources that can replace these finite supplies, examining their potential and challenges.

Energy Resources That Are Non-Renewable

This examination of energy resources that are non-renewable underscores their finite nature and the multifaceted challenges associated with their continued utilization. The analysis has highlighted the long formation timescales, environmental consequences, uneven distribution, and geopolitical implications inherent to these resources. Depletion, environmental impact, fossil fuel formation, geopolitical influence, and limited reserves are defining characteristics that necessitate strategic planning and responsible stewardship.

The imperative for transitioning to sustainable energy alternatives is undeniable. The long-term security and stability of global energy systems depend on proactive measures to conserve remaining resources, enhance energy efficiency, and invest in renewable technologies. A failure to address these challenges will inevitably lead to economic instability, environmental degradation, and heightened geopolitical tensions, jeopardizing the well-being of future generations. The time for decisive action is now.