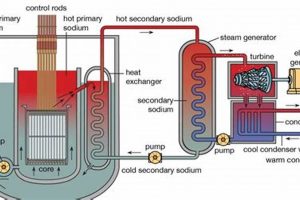

Uranium, a naturally occurring radioactive element, serves as the primary fuel in nuclear power plants. Its atoms undergo a process called nuclear fission, where they are split, releasing substantial amounts of energy in the form of heat. This heat converts water into steam, which drives turbines to generate electricity. The utilization of this element for power production relies on a finite supply extracted from the Earth’s crust.

The debate surrounding the sustainability of nuclear power hinges on whether the resource fueling it is replenished at a rate comparable to its consumption. Unlike solar, wind, or hydropower, which harness ongoing natural processes, the resource in question is a finite mineral. While nuclear power offers high energy density and reduced greenhouse gas emissions compared to fossil fuels, its reliance on a finite resource raises questions about its long-term viability and the potential depletion of accessible reserves. Historically, the perception of this element’s abundance has shifted with advancements in extraction techniques and variations in demand.

Therefore, an examination of the resource’s availability, usage rates, and the feasibility of alternative fuel cycles becomes crucial in determining its classification as a sustainable energy option. Discussions regarding breeder reactors, which can produce more fissile material than they consume, and the potential of extracting this element from seawater further complicate the assessment of its renewability.

Considerations Regarding Uranium as an Energy Resource

The evaluation of uranium as a viable energy source necessitates a careful examination of several key factors. These considerations inform the discussion on whether this resource can be regarded as sustainable.

Tip 1: Assess Resource Abundance: A thorough understanding of the Earth’s uranium reserves is paramount. Analyze geological surveys and estimations of economically recoverable quantities to determine the longevity of the resource.

Tip 2: Evaluate Extraction Technologies: Consider the environmental impact and energy requirements of uranium mining and milling. Improved extraction methods can potentially increase the availability of the resource while minimizing negative consequences.

Tip 3: Investigate Fuel Cycle Options: Explore the potential of advanced fuel cycles, such as breeder reactors, which can generate more fissile material than they consume, thereby extending the lifespan of uranium resources.

Tip 4: Analyze Energy Density and Efficiency: Nuclear power possesses a high energy density compared to many renewable sources. Evaluate the overall energy efficiency of nuclear power plants and identify areas for improvement.

Tip 5: Examine Waste Management Strategies: Safe and effective disposal of nuclear waste is crucial for the long-term sustainability of nuclear energy. Investigate advancements in waste storage and disposal technologies, including geological repositories.

Tip 6: Account for Security Concerns: The potential for nuclear proliferation and the vulnerability of nuclear facilities to terrorist attacks must be addressed. Implement robust security measures and international safeguards to mitigate these risks.

Tip 7: Consider Environmental Impact: Evaluate the environmental impact of the entire nuclear fuel cycle, from uranium mining to waste disposal. Identify and mitigate potential risks to air, water, and soil quality.

These considerations highlight the complex nature of determining the sustainability of uranium as an energy source. A comprehensive assessment must account for resource availability, technological advancements, environmental impact, and security concerns.

Ultimately, a balanced perspective is required to determine whether uranium can contribute to a sustainable energy future. Further research and development are necessary to address the challenges and maximize the potential benefits of nuclear power.

1. Finite resource

The classification of uranium as a finite resource is central to evaluating if it can be considered a renewable energy source. The fixed quantity of uranium available on Earth distinguishes it from resources that replenish naturally over time.

- Depletion of Uranium Deposits

Uranium is extracted from specific geological formations where it is concentrated. These deposits are exhaustible, meaning that once extracted, the resource is not naturally replenished within a human timescale. The ongoing use of uranium in nuclear reactors steadily depletes these reserves, requiring the discovery and exploitation of new deposits, which becomes increasingly challenging and costly over time. This inherent limitation contradicts the fundamental characteristic of renewability.

- Geographic Concentration of Resources

Uranium resources are not evenly distributed across the globe. A relatively small number of countries possess the majority of economically viable uranium deposits. This geographic concentration introduces geopolitical dependencies and potential supply vulnerabilities. Access to uranium is contingent on these limited sources, further reinforcing its status as a non-renewable resource subject to the constraints of geological availability and political factors.

- Energy Return on Investment (EROI) Considerations

The energy required to extract and process uranium ore must be considered in the context of its overall energy contribution. As easily accessible, high-grade uranium deposits are depleted, the energy input required to extract lower-grade ores increases. This impacts the Energy Return on Investment (EROI) of uranium, potentially diminishing its net energy contribution and further distinguishing it from renewable sources that generally have lower energy input requirements.

- Long-Term Availability vs. Demand

Projections of uranium demand, driven by the expansion of nuclear power, must be considered against estimates of available resources. While estimates of uranium reserves vary, the underlying reality remains that these reserves are finite. If demand outpaces the rate of discovery and extraction of new economically viable deposits, the long-term availability of uranium could become a limiting factor for nuclear power generation. This inherent constraint contrasts with the concept of renewability, which implies a virtually inexhaustible supply.

The attributes of finite resource outlined above directly counter the characteristics associated with renewable energy sources. The exhaustible nature of uranium deposits, its geographic concentration, the energy requirements for extraction, and the potential imbalance between long-term availability and demand collectively reinforce the conclusion that, regardless of its potential benefits in power generation, uranium is not a renewable energy source.

2. Fission-dependent energy

The core principle underpinning nuclear power generation, fission, directly impacts any evaluation of whether uranium qualifies as a renewable energy source. The reliance on nuclear fission as the energy-producing mechanism establishes fundamental limitations regarding resource replenishment.

- Non-Renewable Fuel Consumption

Nuclear fission involves splitting uranium atoms to release energy. This process consumes the uranium fuel, transforming it into fission products. Once uranium undergoes fission, it is no longer available as a fuel source. This consumptive nature distinguishes it from renewable energy sources like solar or wind, which harness energy from continuously available natural processes. Fission inherently relies on depleting a finite resource.

- Absence of Natural Replenishment

Uranium does not naturally regenerate at a rate comparable to its consumption in nuclear reactors. While new uranium deposits may form over geological timescales, these processes are far too slow to replenish the uranium being used for power generation. This lack of natural replenishment directly contradicts the definition of a renewable resource, which is characterized by its ability to be replenished within a human timeframe.

- Byproduct Generation and Disposal

Nuclear fission produces radioactive byproducts, including spent nuclear fuel. These byproducts require careful management and disposal due to their long-term radioactivity. The creation of radioactive waste introduces environmental challenges and adds to the overall lifecycle impacts of nuclear power. Renewable energy sources generally do not produce comparable levels of hazardous waste that necessitate long-term isolation from the environment.

- Fuel Cycle Considerations

While advanced fuel cycles, such as breeder reactors, can potentially extend the lifespan of uranium resources by converting non-fissile isotopes into fissile material, these technologies do not fundamentally alter the fission-dependent nature of nuclear power. Even with breeder reactors, uranium or other fissile materials are ultimately consumed through fission, and the process generates radioactive waste. The fuel cycle may improve resource utilization but does not make uranium a renewable resource.

The fission-dependent nature of nuclear power inherently links its energy generation to the consumption of a finite resource. This consumption, coupled with the lack of natural replenishment and the generation of radioactive waste, firmly positions uranium outside the realm of renewable energy sources. Advanced technologies may mitigate some limitations, but the fundamental dependence on fission remains a defining characteristic.

3. Breeder reactor potential

Breeder reactor technology is a crucial consideration in evaluating the long-term viability of nuclear power and its potential relevance to discussions surrounding resource sustainability. The capacity of these reactors to produce more fissile material than they consume during operation raises questions about efficient resource utilization within nuclear energy production.

- Enhanced Fuel Utilization

Breeder reactors, unlike conventional reactors, have the capability to convert fertile isotopes, such as uranium-238 or thorium-232, into fissile isotopes like plutonium-239 or uranium-233. This process significantly enhances the utilization of uranium resources, potentially extending the lifespan of available reserves. For instance, a conventional reactor primarily uses uranium-235, which constitutes a small fraction of natural uranium, while a breeder reactor can utilize the more abundant uranium-238. By converting the non-fissile uranium-238 into fissile plutonium-239, the breeder reactor effectively creates more fuel than it consumes, in terms of fissile material. This aspect is critical when assessing long-term fuel availability.

- Waste Reduction Possibilities

While breeder reactors still generate nuclear waste, some designs have the potential to reduce the volume and radiotoxicity of the waste compared to conventional reactors. Certain advanced breeder reactor concepts can transmute long-lived radioactive isotopes into shorter-lived or stable isotopes, potentially reducing the long-term burden of nuclear waste disposal. However, it is important to acknowledge that this capability does not eliminate the need for waste management but rather alters its characteristics and requirements.

- Resource Independence Implications

Widespread adoption of breeder reactor technology could reduce dependence on newly mined uranium. By utilizing existing stockpiles of depleted uranium and thorium, breeder reactors could provide a more secure and sustainable fuel supply for nuclear power. This shift could reduce the geopolitical implications associated with uranium mining and enrichment, as nations would rely less on uranium imports. However, building and operating breeder reactors require a significant technological and financial investment.

- Economic and Proliferation Challenges

Despite their potential benefits, breeder reactors face significant challenges related to economics and nuclear proliferation. The cost of constructing and operating breeder reactors is typically higher than that of conventional reactors. The economic competitiveness of breeder reactor technology remains a barrier to widespread adoption. Additionally, the production of plutonium in breeder reactors raises proliferation concerns, as plutonium is a fissile material that can be used in nuclear weapons. Managing and safeguarding plutonium in the fuel cycle is essential to prevent diversion for illicit purposes.

The potential benefits of breeder reactor technology in extending uranium resource utilization and potentially reducing waste generation are significant factors in the debate regarding nuclear power’s long-term viability. However, the economic, safety, and proliferation challenges associated with breeder reactors must be addressed to determine whether this technology can contribute to a more sustainable energy future. While breeder reactors enhance resource efficiency, they do not fundamentally transform uranium into a resource that replenishes itself at a rate comparable to consumption, thus not classifiable as renewable.

4. Waste disposal challenges

The issue of nuclear waste disposal presents a significant challenge to the proposition of nuclear energy’s sustainability. The spent nuclear fuel, a byproduct of uranium fission, contains highly radioactive materials requiring long-term isolation from the biosphere. The persistence of radioactivity for thousands of years necessitates the development and maintenance of secure storage solutions, such as deep geological repositories. These repositories aim to prevent the release of radioactive materials into the environment, a complex engineering and geological undertaking. The absence of universally accepted and operational long-term disposal sites in numerous countries with nuclear power programs highlights the ongoing challenges in this area. For example, the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository project in the United States faced significant political and public opposition, leading to its abandonment. This exemplifies the difficulties associated with establishing permanent waste disposal solutions.

The quantity of spent nuclear fuel continues to accumulate globally, posing both logistical and environmental concerns. Interim storage solutions, such as on-site storage pools and dry cask storage, are utilized while awaiting permanent disposal sites. However, these interim solutions are not intended for indefinite storage and raise concerns about long-term safety and security. Furthermore, the potential for accidents or breaches in containment, although rare, necessitates rigorous safety protocols and emergency response plans. The cost associated with managing nuclear waste, including storage, transportation, and eventual disposal, represents a substantial component of the overall cost of nuclear power generation. These costs can influence the economic competitiveness of nuclear energy compared to other energy sources.

The unresolved issue of nuclear waste disposal significantly impacts the assessment of nuclear energy’s sustainability. While nuclear power offers advantages in terms of energy density and reduced greenhouse gas emissions compared to fossil fuels, the long-term environmental burden associated with waste disposal raises questions about its long-term viability. Until viable and universally accepted long-term disposal solutions are implemented, nuclear energy faces limitations in achieving true sustainability. The challenges of waste disposal underscores the reality that uranium is not a renewable energy source, as its lifecycle inherently generates long-lasting and hazardous waste products that require continuous management and pose ongoing environmental risks.

5. Geopolitical resource control

The geographic distribution of uranium deposits exerts a significant influence on the perception of whether uranium constitutes a renewable energy source. The concentration of uranium resources within a limited number of nations creates geopolitical dependencies, potentially impacting energy security for countries reliant on nuclear power. This control over resources contrasts sharply with renewable sources, such as solar or wind, which are more evenly distributed geographically and therefore less susceptible to geopolitical manipulation. For instance, countries with significant uranium reserves, like Kazakhstan, Canada, and Australia, wield considerable influence over the global supply chain. Nations lacking domestic uranium reserves become reliant on international trade and agreements, exposing them to potential disruptions in supply due to political instability, trade disputes, or resource nationalism. This dependency undermines the notion of resource independence often associated with renewable energy.

Furthermore, the control of uranium enrichment technologies adds another layer of geopolitical complexity. Uranium enrichment, a process necessary to produce fuel for most nuclear reactors, is dominated by a few countries. Access to enrichment services is crucial for nations operating nuclear power plants, further consolidating geopolitical power in the hands of those controlling the technology. The Iranian nuclear program and the international efforts to monitor and constrain it illustrate the sensitivity surrounding uranium enrichment and its potential to impact international relations. This contrasts with renewable energy technologies, which are generally more accessible and less reliant on specialized infrastructure controlled by a limited number of nations.

In conclusion, the concentration of uranium resources and enrichment technologies in a few countries creates geopolitical vulnerabilities that contradict the ideals of resource independence and security often associated with sustainable energy solutions. This geopolitical dimension, coupled with uranium’s finite nature and waste disposal challenges, reinforces the understanding that uranium, despite its potential contributions to energy production, fundamentally differs from renewable resources that offer greater geographic diversity and reduced geopolitical risks. The control over uranium, therefore, necessitates a careful evaluation of its long-term sustainability within the global energy landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following questions and answers address common inquiries and misconceptions surrounding the classification of uranium within the context of energy sustainability.

Question 1: Is uranium, by definition, considered a renewable resource?

No. Uranium is a finite resource extracted from the Earth’s crust. Its quantity is limited, and it does not regenerate on a human timescale, contrasting with renewable resources like solar or wind.

Question 2: Does the high energy density of uranium influence its classification as renewable?

No. Energy density is a measure of energy content per unit mass or volume. While uranium possesses high energy density, this characteristic does not alter its fundamental nature as a non-renewable resource. Renewability is determined by resource replenishment, not energy output.

Question 3: Could advanced reactor technologies, such as breeder reactors, reclassify uranium as a renewable resource?

No. Breeder reactors enhance uranium resource utilization by converting non-fissile isotopes into fissile material. However, they do not create uranium. The technology extends the lifespan of existing resources but does not transform uranium into a self-replenishing source.

Question 4: How does the environmental impact of uranium mining and processing affect its classification as renewable?

The environmental consequences of uranium mining, milling, and enrichment processes, including habitat disruption and water contamination, are relevant to assessing the overall sustainability of nuclear power. However, environmental impact does not directly determine whether a resource is renewable. Renewability is solely dependent on the rate of natural replenishment.

Question 5: Does the generation of nuclear waste preclude uranium from being considered a renewable resource?

The production of long-lived radioactive waste represents a significant challenge for nuclear power. While waste management practices impact the sustainability of nuclear energy, the creation of waste itself does not directly define a resource as renewable or non-renewable. Waste generation is a consequence of uranium fission, not a characteristic of the resource itself.

Question 6: What role does geopolitical control over uranium resources play in classifying it as renewable?

The concentration of uranium resources in a limited number of countries creates geopolitical dependencies. These dependencies, while relevant to energy security, do not influence the fundamental classification of uranium as a finite, non-renewable resource. Geographic distribution and control are separate considerations from resource renewability.

In summary, uranium’s classification remains rooted in its exhaustible nature and absence of natural replenishment within a human timeframe. Technological advancements and geopolitical factors do not alter this fundamental characteristic.

This concludes the frequently asked questions. Next, we will explore the benefits and drawbacks of uranium to understand whether or not uranium is a renewable energy source.

Conclusion

The preceding exploration of “is uranium a renewable energy source” has rigorously examined various facets, including resource availability, fission dependency, breeder reactor technology, waste disposal challenges, and geopolitical considerations. Analysis of these factors consistently demonstrates that uranium does not meet the criteria defining a renewable resource. Its finite quantity, reliance on consumptive fission, and the enduring legacy of radioactive waste solidify its classification as a non-renewable energy source. Alternative fuel cycles and advanced reactor designs offer potential improvements in resource utilization and waste management; however, they do not fundamentally alter uranium’s inherent limitations regarding replenishment.

Therefore, while nuclear power presents advantages in terms of energy density and reduced greenhouse gas emissions compared to fossil fuels, its reliance on uranium necessitates a realistic assessment of its long-term sustainability. Future energy strategies must carefully weigh the benefits of nuclear power against the challenges of resource depletion, waste management, and geopolitical dependencies. Continued research and development into alternative energy sources, alongside responsible management of uranium resources, remain crucial for securing a sustainable energy future.