Fossil fuels, such as coal, petroleum, and natural gas, represent finite energy sources formed over millions of years from the remains of organic matter. These materials provide a substantial portion of the world’s energy, powering industries, transportation, and electricity generation. Nuclear fuels, like uranium, also fall into this category, being a naturally occurring element that is extracted and processed for use in nuclear reactors to produce electricity.

Reliance on these options has historically driven industrial growth and technological advancement, offering readily available and relatively inexpensive energy solutions. However, their extraction, processing, and combustion pose significant environmental consequences. These include greenhouse gas emissions contributing to climate change, air and water pollution, and habitat destruction. Furthermore, the geographically uneven distribution of these resources can lead to geopolitical tensions and economic dependencies.

The continued use of these energy sources necessitates a careful examination of their long-term impact and consideration of alternative, sustainable energy solutions. This includes exploring renewable energy technologies and implementing strategies for energy conservation and efficiency, aiming to mitigate the environmental and societal costs associated with the traditional energy paradigm. Further discussion will delve into the specific characteristics, utilization, and environmental considerations of these finite resources, as well as the potential of alternative energy systems.

Responsible Management of Finite Energy Sources

The following outlines strategies for the informed and conscientious use of depletable energy commodities, recognizing their environmental and geopolitical implications.

Tip 1: Prioritize Energy Efficiency: Implement measures to reduce energy consumption across all sectors, including industry, transportation, and residential buildings. Examples include upgrading insulation, utilizing energy-efficient appliances, and optimizing industrial processes.

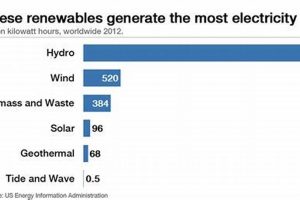

Tip 2: Diversify Energy Sources: Reduce dependence on a single option by developing a portfolio of energy sources, including renewable technologies, alongside existing infrastructure. This enhances energy security and mitigates price volatility.

Tip 3: Invest in Research and Development: Support ongoing research into cleaner and more efficient extraction, processing, and utilization technologies. This includes carbon capture and storage, as well as advanced nuclear reactor designs.

Tip 4: Implement Carbon Pricing Mechanisms: Establish carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems to internalize the environmental costs associated with emissions. This incentivizes emission reductions and promotes the adoption of cleaner alternatives.

Tip 5: Promote Public Awareness: Educate the public on the environmental and economic consequences associated with reliance on finite resources. Encourage informed decision-making regarding energy consumption and investment in sustainable alternatives.

Tip 6: Develop Strategic Reserves: Maintain strategic reserves of crucial resources, such as oil and natural gas, to buffer against supply disruptions and price shocks. This enhances energy security during periods of geopolitical instability or natural disasters.

Tip 7: Advocate for International Cooperation: Encourage international collaboration to address global energy challenges and promote sustainable practices. This includes sharing best practices, coordinating research efforts, and establishing common environmental standards.

These strategies emphasize the importance of proactive planning and responsible resource management to mitigate the risks associated with reliance on depletable energy commodities and promote a more sustainable energy future.

The subsequent sections will explore the role of policy interventions and technological innovations in achieving a more secure and environmentally responsible energy system.

1. Depletion

The depletion of non-renewable resources is a fundamental characteristic directly tied to their definition and utilization. Unlike renewable resources that can be replenished over a relatively short period, these sources exist in finite quantities and are consumed at rates that far exceed natural replenishment processes. This disparity between consumption and regeneration is the defining feature of depletion and a critical concern for long-term energy security and environmental sustainability. The extraction and use of fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, serve as primary examples of this phenomenon. As these fuels are burned to generate energy, their stored carbon is released into the atmosphere, and the original resource is irretrievably consumed. The rate of consumption, driven by global energy demand, is vastly greater than the rate at which these resources formed millions of years ago.

The consequences of depletion extend beyond the mere exhaustion of resources. As readily accessible deposits are depleted, extraction becomes more difficult and expensive, often requiring more energy and advanced technologies to access remaining reserves. This can lead to higher energy prices, increased environmental impacts, and geopolitical instability as nations compete for dwindling supplies. For example, the depletion of easily accessible oil reserves has led to increased exploration and exploitation of unconventional resources, such as shale oil and tar sands, which have significantly higher environmental footprints. Furthermore, the concept of “peak oil” highlights the point at which global oil production reaches its maximum and begins to decline, potentially triggering significant economic and social disruptions.

In summary, the concept of depletion underscores the inherent limitations of non-renewable resources and the imperative for a transition towards sustainable energy alternatives. Understanding the dynamics of resource depletion is crucial for developing effective energy policies, promoting resource conservation, and investing in renewable energy technologies. Failure to address the challenge of depletion will inevitably lead to increased environmental degradation, economic instability, and geopolitical conflict. The long-term viability of human society depends on a fundamental shift towards a more sustainable and resource-efficient energy system.

2. Environmental Impact

The environmental impact associated with finite energy options is a multifaceted issue encompassing various stages of resource extraction, processing, transportation, and utilization. These activities introduce pollutants into the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and lithosphere, causing ecological disturbances and health hazards. The extent of these impacts necessitates a comprehensive evaluation to inform sustainable energy practices and policy development.

- Air Pollution

The combustion of fossil fuels, particularly coal and petroleum, releases substantial quantities of air pollutants, including particulate matter (PM), sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). These pollutants contribute to respiratory illnesses, acid rain, and the formation of ground-level ozone, a major component of smog. Coal-fired power plants are prime examples, emitting large volumes of SO2 that necessitate flue gas desulfurization technologies to mitigate acid rain formation. Vehicular emissions from gasoline and diesel combustion also contribute significantly to urban air pollution and respiratory health problems.

- Water Contamination

The extraction and processing of energy sources can lead to significant water contamination. Mining operations, such as coal mining and uranium extraction, can release heavy metals, acids, and radioactive materials into nearby water bodies, harming aquatic ecosystems and potentially contaminating drinking water sources. Fracking, used to extract natural gas and oil from shale formations, poses risks of groundwater contamination from hydraulic fracturing fluids and methane leakage. Oil spills, whether from tanker accidents or pipeline failures, can devastate marine and coastal environments, causing long-term damage to ecosystems and fisheries.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The combustion of fossil fuels is a primary contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2). These emissions drive global climate change, leading to rising temperatures, sea-level rise, altered precipitation patterns, and more frequent extreme weather events. Methane, a potent greenhouse gas, is also released during the extraction and transportation of natural gas and coal. The continued reliance on energy sources necessitates a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions through energy efficiency measures, carbon capture and storage technologies, and the transition to renewable energy sources.

- Habitat Destruction

The extraction of energy sources often requires extensive land use, leading to habitat destruction and ecosystem fragmentation. Mountaintop removal coal mining, for instance, devastates entire ecosystems and alters landscapes permanently. Oil and gas exploration can disrupt wildlife habitats and migratory routes. The construction of large-scale energy infrastructure, such as pipelines and power plants, can fragment landscapes and impact biodiversity. Mitigating habitat destruction requires careful planning, environmental impact assessments, and the implementation of restoration measures to minimize the footprint of energy development.

These facets highlight the extensive and diverse environmental consequences associated with finite energy options. Addressing these impacts requires a comprehensive approach encompassing technological innovation, policy interventions, and a shift towards sustainable energy practices. The development and implementation of renewable energy technologies, coupled with stringent environmental regulations, are crucial for mitigating the negative environmental consequences of current energy production and consumption patterns and ensuring a sustainable energy future. Ultimately, minimizing the environmental impact of energy resources necessitates a transition towards a more circular economy and a reduction in overall energy demand.

3. Geopolitical Risks

The global distribution and control of depleteable resources, particularly fossil fuels, are intrinsically linked to geopolitical risks, influencing international relations, economic stability, and national security strategies. Competition for access to these finite commodities frequently engenders political tensions and conflicts, necessitating a thorough understanding of these interconnected dynamics.

- Resource Scarcity and Competition

Uneven distribution of reserves concentrates power in specific nations, fostering competition among consumers. Nations reliant on imports may exert political or military influence to secure supply routes and favorable trade agreements. The South China Sea, contested for its potential oil and gas reserves, exemplifies this, with overlapping territorial claims creating regional instability and escalating military presence.

- Price Volatility and Economic Instability

Dependence on energy options makes economies vulnerable to price fluctuations driven by geopolitical events. Supply disruptions, such as those arising from conflicts or political instability in major producing regions, can trigger economic recessions and social unrest. The oil crises of the 1970s demonstrated how geopolitical events in the Middle East could destabilize global economies dependent on oil imports.

- Resource Nationalism and State Control

Producer nations may exercise control over extraction and export to maximize revenue or exert political leverage. This can lead to nationalization of assets, trade embargos, or the manipulation of production levels to influence global markets. Venezuela’s nationalization of its oil industry and its use of oil as a tool for foreign policy illustrate the potential for resource nationalism to affect international relations.

- Conflict and Security Concerns

Control over strategic reserves can be a source of conflict, both internal and international. Armed conflicts may erupt over territory or resources, destabilizing regions and creating humanitarian crises. The ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, often intertwined with control over oil and gas resources, exemplify the security challenges associated with resource competition.

These facets underscore the critical importance of diversifying energy sources and reducing reliance on geographically concentrated supplies. Transitioning towards renewable energy technologies, promoting energy efficiency, and fostering international cooperation are essential strategies for mitigating geopolitical risks and promoting a more stable and sustainable energy future. Furthermore, understanding the complex interplay between resource availability, political power, and economic interests is crucial for navigating the challenges of a world increasingly shaped by resource scarcity and climate change.

4. Economic Dependency

Economic dependency, in the context of finite energy sources, arises when a nation’s economy is significantly reliant on the extraction, processing, consumption, or trade of these commodities. This reliance manifests in several ways: substantial portions of GDP derived from resource extraction, a significant proportion of export revenue originating from these commodities, and/or a critical reliance on imported energy to sustain economic activity. This dependency creates vulnerabilities that can impact economic stability, national security, and geopolitical positioning. The inherent finite nature of these resources exacerbates these vulnerabilities, as depletion inevitably leads to shifts in economic power and necessitates adaptation strategies.

Nations heavily reliant on resource extraction often experience what is termed the “resource curse,” characterized by stunted diversification, corruption, and vulnerability to price fluctuations. For example, many OPEC nations, while enjoying significant wealth from oil exports, struggle to develop other sectors of their economies. Conversely, nations highly dependent on energy imports are susceptible to supply disruptions and price volatility, necessitating strategic reserves and diversification efforts. Germany’s historical reliance on Russian natural gas highlights this dependency, making its economy vulnerable to geopolitical tensions. The practical significance of understanding this dynamic lies in the necessity for governments to implement policies promoting diversification, investing in renewable energy sources, and fostering greater energy independence. A failure to address economic dependency can result in prolonged economic stagnation, increased social inequality, and vulnerability to external shocks.

In conclusion, the connection between economic dependency and energy options presents both opportunities and challenges. While these commodities can drive economic growth, they also create vulnerabilities that demand careful management and strategic planning. Overcoming economic dependency requires a multifaceted approach encompassing economic diversification, technological innovation, and robust regulatory frameworks. By acknowledging the inherent risks and proactively addressing these challenges, nations can mitigate the negative consequences and build more resilient and sustainable economies. The transition to a diversified energy portfolio, emphasizing renewable sources and energy efficiency, remains crucial for achieving long-term economic security and reducing the vulnerabilities associated with finite resources.

5. Resource Distribution

The geographical distribution of finite energy commodities is markedly uneven, a fundamental characteristic that shapes global energy markets, geopolitical dynamics, and economic dependencies. This unevenness significantly influences the accessibility, affordability, and strategic importance of energy for various nations. The concentration of fossil fuel reserves in specific regions, such as the Middle East for oil and Russia for natural gas, creates a supply-demand imbalance that necessitates international trade and complex transportation networks. This disparity has profound implications: nations with abundant deposits often wield significant economic and political power, while those lacking indigenous resources become dependent on external sources, impacting their energy security and vulnerability to price fluctuations.

Real-world examples illustrate the practical significance of resource distribution. The strategic importance of the Strait of Hormuz, a narrow waterway through which a substantial portion of global oil supplies transits, highlights the vulnerability of global energy supply chains to disruptions. Similarly, the dependence of European nations on Russian natural gas has been a source of geopolitical tension, particularly in light of conflicts and political disagreements. Resource distribution also affects energy infrastructure development. Nations with readily available and inexpensive fossil fuels may be less incentivized to invest in renewable energy technologies, while those lacking such resources are often driven to explore alternative options for energy security. This geographical inequality prompts international collaborations, trade agreements, and strategic alliances aimed at securing access to energy resources, shaping international relations and driving global energy policy.

In conclusion, the uneven distribution of finite energy commodities is a central factor influencing global energy dynamics, with substantial consequences for economic stability, national security, and geopolitical relationships. A comprehensive understanding of this factor is crucial for effective energy policy planning, risk mitigation, and promoting a more equitable and sustainable energy future. Addressing the challenges associated with skewed resource distribution requires international cooperation, investment in diverse energy sources, and the development of efficient and resilient supply chains to ensure access to affordable and reliable energy for all nations. The transition to renewable energy sources offers the potential to mitigate some of these challenges, as renewable resources are more evenly distributed geographically, albeit with their own unique challenges related to intermittency and infrastructure.

6. Combustion Byproducts

The combustion of finite energy commodities, primarily fossil fuels, invariably produces byproducts that significantly impact the environment and human health. These byproducts are a direct consequence of the chemical reactions that occur when these resources are burned to generate energy, and their composition varies depending on the type of fuel and the combustion conditions. The primary finite resources, coal, petroleum, and natural gas, release carbon dioxide (CO2), water vapor (H2O), and a variety of pollutants as a result of combustion. The critical byproduct of concern is CO2, a greenhouse gas that contributes to global climate change by trapping heat in the atmosphere. Incomplete combustion and impurities in the fuel result in additional byproducts, including particulate matter (PM), sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon monoxide (CO), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). These pollutants contribute to air pollution, respiratory illnesses, acid rain, and other environmental problems. The significance of these byproducts lies in their cumulative effect on the environment and public health, underscoring the urgency to mitigate emissions through technological innovation and policy interventions. For instance, coal-fired power plants generate substantial amounts of SO2, necessitating flue gas desulfurization to reduce acid rain. Vehicle exhaust from gasoline and diesel engines emits NOx and VOCs, contributing to smog formation in urban areas. Methane leakage during natural gas extraction and transportation further exacerbates greenhouse gas emissions, despite natural gas burning cleaner than coal or oil.

The practical implications of understanding combustion byproducts extend to several areas, including technology development, regulatory compliance, and sustainable energy planning. Technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) aim to capture CO2 emissions from power plants and industrial facilities, preventing their release into the atmosphere. Catalytic converters in vehicles reduce NOx and VOC emissions, while stricter emission standards for power plants and industries limit the release of particulate matter and sulfur dioxide. From a policy perspective, carbon pricing mechanisms, such as carbon taxes and cap-and-trade systems, incentivize emission reductions by placing a cost on carbon emissions. Furthermore, the analysis of combustion byproducts informs the development of cleaner-burning fuels and the transition to alternative energy sources, such as renewable energy technologies, which produce significantly fewer or no combustion byproducts. For example, the adoption of electric vehicles reduces tailpipe emissions, while renewable energy sources like solar and wind power do not produce combustion byproducts during electricity generation.

In summary, combustion byproducts are an inherent consequence of using finite energy commodities, posing significant environmental and health challenges. Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach encompassing technological innovation, stringent regulatory standards, and a strategic shift towards sustainable energy alternatives. The long-term sustainability of the energy system depends on minimizing combustion byproducts and mitigating their impact on the environment and human health. Failure to address these issues will perpetuate climate change, air pollution, and other environmental problems, undermining the well-being of present and future generations. The key lies in transitioning to energy systems that prioritize sustainability, efficiency, and environmental stewardship.

Frequently Asked Questions About Finite Energy Commodities

The following addresses common inquiries regarding the nature, utilization, and implications of these resources, aiming to provide clarity and enhance understanding.

Question 1: What distinguishes finite energy sources from renewable alternatives?

Finite sources exist in fixed quantities, formed over geological timescales, and consumed at rates exceeding natural replenishment. Renewable options, conversely, are naturally replenished and can be utilized sustainably without depletion.

Question 2: What are the primary environmental consequences associated with the utilization of finite commodities?

Environmental impacts include air and water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions contributing to climate change, habitat destruction from extraction activities, and potential for soil contamination.

Question 3: How does the geographically uneven distribution of these resources impact international relations?

Uneven distribution creates dependencies and competition, fostering geopolitical tensions as nations vie for access and control, potentially leading to conflicts and economic coercion.

Question 4: What are the principal strategies for mitigating the environmental impacts of finite energy utilization?

Mitigation strategies encompass enhancing energy efficiency, adopting carbon capture and storage technologies, transitioning to cleaner energy sources, and implementing stringent environmental regulations.

Question 5: How does economic dependency on these commodities affect national economies?

Economic dependency creates vulnerabilities to price fluctuations, supply disruptions, and the “resource curse,” characterized by limited economic diversification and potential for corruption.

Question 6: What role does technological innovation play in the future of these energy options?

Technological advancements are crucial for improving extraction efficiency, reducing emissions, developing carbon capture technologies, and exploring alternative uses of these commodities beyond combustion.

In summation, understanding the characteristics and implications of finite energy resources is crucial for informed decision-making and the development of sustainable energy policies.

The subsequent section will delve into the specific characteristics of various finite energy commodities, including coal, oil, natural gas, and nuclear fuels, providing detailed insights into their extraction, processing, and utilization.

Conclusion

The preceding analysis has elucidated the multifaceted implications associated with reliance on “example non renewable resources.” From the inherent limitations imposed by finite reserves to the pervasive environmental consequences and complex geopolitical dynamics, it is evident that continued dependence on these options presents substantial challenges. The uneven distribution of these resources exacerbates economic dependencies and vulnerabilities, while combustion byproducts contribute significantly to climate change and air pollution. These factors collectively underscore the imperative for a strategic shift towards sustainable energy alternatives.

Consideration of the long-term societal well-being necessitates a concerted effort to diversify energy portfolios, promote energy efficiency, and invest in renewable energy technologies. The pursuit of innovative solutions and responsible resource management will be essential in mitigating the adverse effects associated with “example non renewable resources” and ensuring a more secure and sustainable energy future. Sustained commitment to this transition remains critical for addressing the challenges of energy security and environmental stewardship, safeguarding the well-being of current and future generations.