A defining feature shared among solar, wind, geothermal, hydro, and biomass energy sources is their capacity for natural replenishment within a human lifespan. These resources are not depleted through utilization, unlike fossil fuels which exist in finite quantities. For example, solar radiation consistently reaches the Earth, and wind patterns are continually driven by atmospheric processes.

This inherent renewability contributes significantly to long-term energy security and environmental sustainability. By relying on sources that naturally regenerate, dependence on finite reserves is reduced, mitigating resource scarcity concerns. Furthermore, the utilization of these resources often produces minimal or no greenhouse gas emissions, lessening the impact on climate change. Historically, many of these energy forms, such as hydropower and wind power, have been utilized for centuries, demonstrating their enduring availability.

Consequently, understanding the principles and technologies that harness this consistent availability is paramount to transitioning towards a more sustainable and resilient energy future. Subsequent discussions will delve into the specific mechanisms by which various types of energy are captured, converted, and integrated into existing energy infrastructure.

Considerations for Maximizing the Value of Replenishable Energy Sources

Optimizing the integration of energy resources capable of natural replenishment requires careful planning and execution across technological, economic, and policy dimensions.

Tip 1: Diversify Energy Portfolios: Reliance on a single renewable source exposes energy systems to intermittency challenges and regional weather patterns. Diversification across solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal resources can mitigate these risks.

Tip 2: Invest in Energy Storage Solutions: The intermittent nature of some replenishable resources necessitates energy storage technologies. Battery storage, pumped hydro storage, and thermal energy storage can buffer fluctuations in energy supply and demand.

Tip 3: Modernize Grid Infrastructure: Existing grid infrastructure may be inadequate to handle the distributed nature of many energy sources. Smart grids with enhanced monitoring and control capabilities are essential for efficient integration.

Tip 4: Prioritize Research and Development: Continuous innovation is crucial for improving the efficiency and reducing the cost of harnessing replenishable energy sources. Focused research can unlock new technologies and materials.

Tip 5: Implement Supportive Policy Frameworks: Government policies, such as tax incentives, feed-in tariffs, and renewable energy standards, can create a favorable investment climate and accelerate the adoption of energy sources capable of natural replenishment.

Tip 6: Promote Public Awareness and Education: Public understanding of the benefits and challenges associated with replenishable energy resources is crucial for gaining societal support and driving informed decision-making.

Tip 7: Encourage International Collaboration: Sharing knowledge, best practices, and technological advancements across national borders can accelerate the global transition to a sustainable energy future.

By focusing on diversification, storage, grid modernization, R&D, supportive policies, public awareness, and international collaboration, the full potential of these constantly renewed energy sources can be realized.

In conclusion, strategic planning and coordinated action are necessary to harness the long-term benefits of power sources able to regenerate naturally, enabling a more sustainable energy landscape.

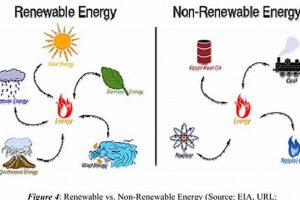

1. Self-replenishment

Self-replenishment constitutes the defining characteristic inherent in energy resources designated as renewable. This attribute dictates that the source material, whether solar radiation, wind, water, or biomass, is naturally restored at a rate comparable to or exceeding its rate of consumption. Without self-replenishment, a resource is considered finite and non-renewable, eventually leading to depletion upon continued extraction. For example, solar energy relies on the continuous nuclear fusion reactions within the sun, an effectively inexhaustible process over human timescales. Similarly, wind energy harnesses the kinetic energy of air currents driven by solar heating and Earth’s rotation, perpetually re-establishing the source.

The importance of self-replenishment extends to the long-term sustainability of energy systems. By utilizing resources that regenerate naturally, dependence on depletable fossil fuels is minimized, mitigating concerns about resource scarcity and price volatility. Moreover, energy sources exhibiting self-replenishment typically generate lower greenhouse gas emissions during operation, contributing to the mitigation of climate change. Geothermal energy exemplifies this, drawing heat from the Earth’s interior, which is continuously replenished by radioactive decay processes. Hydroelectric power leverages the water cycle’s constant evaporation and precipitation to replenish reservoirs.

Understanding the practical implications of self-replenishment is vital for designing effective energy policies and infrastructure. It informs investment decisions, grid management strategies, and the overall transition towards a cleaner energy future. Challenges exist in optimizing the capture and utilization of these naturally replenishing resources, such as addressing the intermittency of solar and wind power and ensuring sustainable biomass harvesting practices. Despite these challenges, the fundamental property of self-replenishment remains the cornerstone of sustainable energy development.

2. Natural availability

Natural availability represents a core component of resources qualified as renewable. This signifies that the fundamental energy source exists freely within the Earth’s environment, accessible for exploitation without the creation of the resource itself. The extent of natural availability directly impacts the feasibility and scalability of utilizing specific energy types. For example, solar irradiance is uniformly accessible across the globe, albeit with variations in intensity based on latitude and atmospheric conditions. This widespread natural availability underpins the potential for global solar energy adoption. Conversely, geothermal resources are concentrated in geologically active regions, limiting their geographically widespread natural availability and therefore their potential in certain locations.

The interplay between natural availability and other factors influences the economic viability of renewable energy projects. High natural availability often translates to lower input costs, reducing the overall expense of energy generation. Wind power installations, for instance, are strategically situated in areas with consistent wind patterns, maximizing energy capture and minimizing operational expenses. Hydroelectric power depends on natural water cycles and suitable topographical features to create reservoirs; the combination of these factors dictates the potential for hydroelectric development in a given region. Biomass, while naturally available, relies on land use and agricultural practices for sustainable production, introducing complexities beyond mere natural occurrence.

Understanding the nuances of natural availability is essential for informed energy policy decisions. While a resource may be naturally present, its accessibility can be constrained by geographical, technological, or environmental limitations. Recognizing these constraints is crucial for realistic renewable energy deployment targets and strategies. The combination of self-replenishment and sufficient natural availability distinguishes these renewable resources from depletable fossil fuels and dictates their long-term potential for sustainable energy provision. Challenges remain in optimizing resource utilization and addressing variability, but these are distinct from the fundamental dependence on nature’s provision.

3. Finite extraction rates

The characteristic of finite extraction rates is an essential, albeit often overlooked, aspect of harnessing inherently renewable energy resources. While the underlying source is naturally replenished, the rate at which this energy can be extracted and converted into usable forms is invariably subject to limitations. Understanding these limitations is crucial for realistic energy planning and sustainable resource management.

- Sustainable Biomass Harvesting

Biomass exemplifies the principle of finite extraction rates. While plant matter regrows, excessive harvesting surpasses the rate of natural replenishment, leading to deforestation, soil degradation, and diminished carbon sequestration. Sustainable forestry and agricultural practices are essential to ensure that biomass extraction remains within ecologically viable limits. This involves careful assessment of growth rates, species selection, and ecosystem health.

- Hydropower Capacity Constraints

Hydropower relies on the continuous water cycle, but the capacity of hydroelectric dams to generate electricity is constrained by several factors. River flow rates vary seasonally and annually, impacting electricity generation potential. Additionally, reservoir size, turbine efficiency, and ecological considerations, such as fish migration, impose further limitations on the rate at which hydroelectric energy can be extracted. Operating hydropower plants sustainably requires balancing energy production with environmental preservation.

- Geothermal Resource Depletion

While geothermal energy draws on the Earth’s internal heat, the rate at which this heat can be extracted from geothermal reservoirs is not limitless. Overexploitation can lead to reservoir cooling and reduced energy output over time. Sustainable geothermal energy extraction involves careful monitoring of reservoir temperatures and pressures, as well as implementing injection strategies to replenish the heat resource. Maintaining a balance between energy extraction and reservoir sustainability is paramount.

- Wind Turbine Density and Efficiency

Wind energy harnesses the kinetic energy of moving air, but the density of wind turbines in a given area is subject to practical limitations. Placing turbines too close together reduces wind speeds and overall energy capture. Turbine efficiency, blade design, and prevailing wind conditions also constrain the rate at which wind energy can be extracted. Optimizing turbine placement and technology is essential to maximize energy production while minimizing environmental impacts and visual intrusion.

Acknowledging the finite extraction rates associated with replenishing energy sources is not a contradiction but rather a refinement of the concept. It highlights the importance of responsible resource management, technological innovation, and integrated planning to ensure that these resources contribute to a truly sustainable energy future. Ignoring these limitations leads to environmental degradation and undermines the long-term viability of renewable energy systems.

4. Decentralized distribution

Decentralized distribution is a notable feature that often accompanies renewable energy sources, influencing their integration into existing energy systems. This contrasts with centralized power generation models, common with fossil fuel-based plants, and necessitates adaptations in grid infrastructure and energy management strategies.

- Distributed Generation at Point of Consumption

Renewable energy installations, such as rooftop solar panels or small-scale wind turbines, frequently operate at or near the point of energy consumption. This reduces transmission losses associated with long-distance power delivery. Residential and commercial buildings can generate their own electricity, decreasing reliance on the central grid and promoting energy independence. Community solar projects exemplify decentralized generation, allowing multiple households to share a single renewable energy source.

- Grid Integration Challenges and Solutions

The decentralized nature of renewable energy presents challenges for maintaining grid stability. Fluctuations in solar and wind power output can impact voltage and frequency. Smart grid technologies, including advanced sensors, controls, and communication networks, are essential for managing these fluctuations and ensuring reliable power delivery. Energy storage solutions, such as batteries, can further mitigate intermittency and enhance grid resilience. Effective grid management is vital for accommodating decentralized renewable energy sources.

- Microgrids and Off-Grid Systems

In remote areas or developing countries, renewable energy sources often form the basis of microgrids or off-grid systems. These systems provide electricity to communities that lack access to the central grid. Solar home systems, powered by photovoltaic panels, provide lighting and power for essential appliances in off-grid households. Microgrids integrate multiple renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and biomass, along with energy storage and control systems, to provide reliable power to local communities. These decentralized systems promote energy access and economic development.

- Community Ownership and Empowerment

Decentralized renewable energy projects often foster community ownership and participation. Local residents can invest in, operate, and benefit from renewable energy installations. Community-owned wind farms and solar cooperatives empower communities to control their energy future and generate local economic benefits. This distributed ownership model contrasts with the centralized ownership structures of conventional energy companies. Community engagement can lead to greater acceptance of renewable energy projects and increased investment in sustainable energy solutions.

The shift towards decentralized distribution of renewable energy sources necessitates innovative approaches to grid management, energy storage, and community engagement. These strategies are crucial for unlocking the full potential of naturally regenerative energy and creating a more resilient, equitable, and sustainable energy future. Examples of decentralized distribution include rooftop solar, community wind projects, and remote microgrids, showcasing the diverse applications and benefits of this approach.

5. Intermittency potential

Intermittency potential, a susceptibility to inconsistent energy production due to fluctuating environmental conditions, constitutes an inherent consideration for many renewable energy resources. This characteristic stems directly from the dependence of these resources on naturally variable phenomena, such as solar irradiance, wind patterns, and river flow rates. The degree of intermittency varies across different resource types; solar power generation is contingent upon daylight hours and cloud cover, while wind power relies on the presence and strength of wind currents. Hydropower, although generally more predictable, can be affected by seasonal variations in rainfall and snowmelt. The presence of this potential directly affects the reliability and dispatchability of electricity generated from these sources.

The management of intermittency necessitates sophisticated strategies for grid integration and energy storage. Grid operators must balance fluctuating renewable energy supply with consistent energy demand, requiring advanced forecasting techniques and responsive control systems. Energy storage technologies, such as battery storage, pumped hydro storage, and thermal energy storage, provide a buffer against supply fluctuations, allowing for the dispatch of renewable energy when it is most needed. Geographical diversification of renewable energy sources also helps to mitigate intermittency; for instance, a geographically distributed network of wind farms can smooth out power output variations. Effective management of intermittency is crucial for maintaining grid stability and ensuring the reliable delivery of renewable energy.

In conclusion, intermittency potential is an intrinsic property of several renewable energy resources, arising from their dependence on variable natural processes. While this presents challenges for grid integration and energy supply reliability, these challenges can be addressed through technological advancements and strategic planning. Addressing intermittency effectively is essential for realizing the full potential of the these naturally available resources and transitioning to a sustainable energy future. Understanding the interplay between resource availability and intermittency is crucial for policy decisions and investment in renewable energy technologies.

6. Varied efficiencies

The inherent renewability shared among solar, wind, hydro, and biomass energy sources does not imply uniform performance. Each technology for harnessing these resources exhibits distinct conversion efficiencies, influencing its economic viability and overall contribution to the energy mix.

- Solar Photovoltaic Conversion

Solar photovoltaic (PV) panels convert sunlight directly into electricity, with efficiencies ranging from 15% to over 20% for commercially available modules. Advanced materials and cell designs are continually improving these efficiencies. This variability stems from cell composition, manufacturing processes, and environmental factors, such as temperature and irradiance levels. Lower efficiencies require larger land areas for equivalent energy production.

- Wind Turbine Aerodynamic Performance

Wind turbines capture kinetic energy from moving air, with theoretical maximum efficiency (Betz limit) around 59%. Modern wind turbines achieve efficiencies of 40-50% under optimal conditions, but this varies based on blade design, wind speed, and turbine size. Larger turbines with advanced airfoil designs can extract more energy from the wind, but performance diminishes in low-wind or turbulent conditions.

- Hydroelectric Power Generation

Hydroelectric power generation exhibits high conversion efficiencies, often exceeding 90% for large-scale dams with modern turbines. Efficiency depends on factors such as water head (height difference between reservoir and turbine), flow rate, and turbine design. Run-of-river hydropower projects, which have smaller reservoirs or no storage, exhibit lower overall energy production due to seasonal flow variations.

- Biomass Conversion Technologies

Biomass energy conversion encompasses a range of technologies, including direct combustion, gasification, and anaerobic digestion, each with distinct efficiencies. Direct combustion of biomass typically achieves efficiencies of 20-30% for electricity generation. Gasification, which converts biomass into a gaseous fuel, can achieve higher efficiencies in combined heat and power (CHP) systems. Anaerobic digestion, which produces biogas from organic waste, has lower electrical efficiencies but can generate valuable fertilizer byproducts.

Varied conversion efficiencies underscore the need for careful technology selection and optimization when deploying regenerating energy sources. Factors such as resource availability, environmental conditions, and economic considerations influence the choice of technology. Improving the conversion efficiencies of all sources is essential for maximizing the contribution of these resources to a sustainable energy future. The common characteristic of renewability is augmented by the continuous pursuit of higher efficiency in converting these resources into usable energy forms.

7. Climate-dependent yield

Climate-dependent yield represents a significant factor influencing the effectiveness of energy resources exhibiting natural regeneration. The output from these sources is inextricably linked to meteorological conditions, creating both opportunities and challenges for energy system planning and grid management. Fluctuations in climate patterns directly affect the amount of energy that can be harvested from various renewable technologies, shaping their reliability and economic viability.

- Solar Irradiance and PV Output

Solar photovoltaic (PV) systems depend directly on solar irradiance, which varies considerably with latitude, season, and weather patterns. Regions with high solar irradiance, such as deserts, offer greater potential for solar energy generation than areas with frequent cloud cover or shorter daylight hours. Seasonal variations in sunlight hours influence PV output, necessitating careful consideration of energy storage solutions or grid integration strategies to compensate for periods of reduced generation. The correlation between climate and PV yield is crucial for assessing the economic feasibility of solar projects and for optimizing grid operations.

- Wind Speed and Wind Turbine Performance

Wind turbine performance is highly sensitive to wind speed, with power output increasing exponentially with wind velocity. Regions with consistent and strong wind patterns, such as coastal areas and mountain passes, are ideal locations for wind farms. However, wind speeds can fluctuate dramatically over short periods and across seasons, leading to intermittency in energy production. Climate change may alter wind patterns, potentially impacting the long-term viability of wind energy projects in certain regions. Understanding the relationship between climate and wind resource availability is essential for strategic wind farm placement and for mitigating risks associated with changing climate conditions.

- Hydrological Cycle and Hydropower Generation

Hydropower relies on the hydrological cycle, specifically precipitation, snowmelt, and river flow rates, to generate electricity. Regions with abundant rainfall and reliable river systems are well-suited for hydropower development. However, climate change is altering precipitation patterns, leading to more frequent droughts and floods, which can significantly impact hydropower generation. Reduced river flow rates during droughts limit electricity production, while extreme flooding can damage dams and turbines. Sustainable hydropower management requires careful consideration of climate variability and adaptation strategies to ensure long-term water resource availability.

- Temperature and Geothermal Energy Production

While geothermal energy draws on heat from the Earth’s interior, its extraction efficiency and resource availability can be influenced by surface temperatures and geological conditions. Ground source heat pumps, for example, rely on the relatively stable temperature of the Earth’s shallow subsurface, but their efficiency can be affected by extreme temperature fluctuations. Geothermal power plants require specific geological formations, such as hydrothermal reservoirs, which may be impacted by changes in groundwater levels due to altered precipitation patterns. Climate change may indirectly affect geothermal energy production by altering groundwater recharge rates and subsurface temperatures, requiring careful monitoring and management of geothermal resources.

Climate-dependent yield, therefore, is a critical factor that influences the planning, operation, and long-term sustainability of multiple energy technologies. Understanding and mitigating the risks associated with climate variability and change is essential for harnessing the full potential of these resources and transitioning to a more resilient and sustainable energy future. Ignoring these climatic factors can lead to unreliable energy supplies and stranded assets, undermining the benefits of natural regeneration. The integration of climate resilience strategies into energy planning is crucial for realizing the long-term value of all resources with natural replenishment.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Defining Trait of Naturally Replenishing Energy

This section addresses common inquiries and clarifies potential misconceptions regarding the shared feature among energy sources deemed renewable: their capacity for natural replenishment.

Question 1: Is the term “renewable” synonymous with “inexhaustible”?

While resources like solar, wind, and hydropower are capable of natural replenishment, they are not necessarily inexhaustible. Sustainable management practices are essential to prevent overexploitation and ensure long-term availability. The rate of extraction must not exceed the rate of regeneration.

Question 2: Does the shared feature mean all renewable energy technologies have similar environmental impacts?

No. Despite the common feature of natural replenishment, the environmental impacts of different energy technologies vary significantly. Hydropower can alter river ecosystems, biomass combustion can release air pollutants, and large-scale solar farms can impact land use. A comprehensive environmental assessment is crucial for each technology.

Question 3: Does the term “renewable” guarantee energy independence?

Not automatically. Energy independence depends on the availability of renewable resources within a specific region and the ability to harness those resources effectively. Reliance on imported technology or materials can limit true energy independence, even with abundant local renewable resources.

Question 4: Does natural replenishment equate to zero-cost energy?

No. While the primary energy source may be freely available, significant costs are associated with infrastructure development, maintenance, and operation. Capital investments in renewable energy technologies can be substantial, and ongoing operational expenses must be factored into the overall cost equation.

Question 5: How does climate change affect resources capable of natural replenishment?

Climate change poses a significant threat to the reliability of some resources with natural regeneration. Altered precipitation patterns can reduce hydropower potential, and changes in wind patterns can affect wind turbine performance. Planning must consider the long-term impacts of climate change on resource availability.

Question 6: Does the shared feature mean all renewable energy sources are equally reliable?

No. Solar and wind energy are intermittent, requiring energy storage solutions or grid management strategies to ensure a consistent power supply. Hydropower, while generally more predictable, can be affected by seasonal variations in water availability. The reliability of these resources depends on geographical location and technological solutions.

In essence, the capacity for natural replenishment is the defining trait, yet various factors influence the practical application and overall sustainability of each technology.

Subsequent sections will delve deeper into specific technological applications of the discussed resource.

The Enduring Significance of Natural Replenishment

The exploration has illuminated the paramount feature shared among energy resources designated as renewable: their inherent capacity for natural replenishment. This characteristic distinguishes solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and sustainable biomass from finite fossil fuels. While these sources vary in their specific operational considerations and environmental impacts, their capacity for natural regeneration provides a fundamental basis for long-term sustainability.

Recognizing the limitations and opportunities associated with resources characterized by natural replenishment is imperative for informed energy policy and technological development. Prioritizing investment in efficient and resilient renewable energy systems is not merely an environmental imperative, but a strategic necessity for securing a stable and sustainable energy future. Continuous innovation and adaptive management are crucial for maximizing the benefits of these inherently regenerative resources.