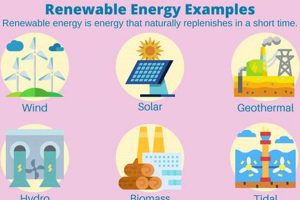

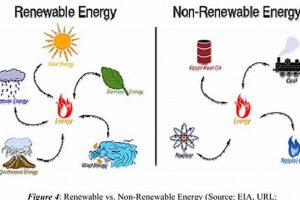

Harnessing power from naturally replenishing sources presents a sustainable alternative to conventional methods. These sources are characterized by their ability to regenerate within a human lifespan, thus mitigating depletion concerns. Several options fall under this category, each with unique characteristics and applications.

Utilizing these methods yields numerous advantages. Environmental impact is significantly reduced due to lower greenhouse gas emissions and decreased reliance on finite resources. Furthermore, the development and deployment of these technologies fosters economic growth and enhances energy security by diversifying energy portfolios. Historically, humans have relied on such methods, notably wind and water, but modern advancements have greatly improved their efficiency and scalability.

Exploring specific instances provides a clearer understanding of their potential. Solar, wind, and hydroelectric power stand out as prominent examples, each warranting detailed examination to ascertain their individual strengths and limitations in contributing to a cleaner energy future.

Harnessing Sustainable Energy

Effective utilization of naturally replenishing energy sources requires careful planning and execution. Maximizing the benefits from these technologies demands adherence to several key principles.

Tip 1: Location Assessment: Conduct thorough site evaluations to determine the optimal placement for energy generation infrastructure. For instance, solar installations should be situated in areas with high solar irradiance, while wind turbines require consistent wind patterns.

Tip 2: Technology Matching: Select technologies appropriate for specific geographical and environmental conditions. Hydropower, for example, is best suited to regions with abundant water resources and suitable topography for dam construction.

Tip 3: Grid Integration Planning: Develop robust strategies for integrating intermittent energy sources into existing power grids. This may involve implementing energy storage solutions or advanced grid management systems to ensure stable power supply.

Tip 4: Regulatory Compliance: Adhere to all relevant environmental regulations and permitting requirements. This includes conducting environmental impact assessments and obtaining necessary approvals to minimize ecological disruption.

Tip 5: Community Engagement: Engage with local communities to foster support for energy projects and address potential concerns. Transparent communication and collaborative decision-making are crucial for ensuring successful implementation.

Tip 6: Investment in Research and Development: Support ongoing research and development efforts to improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of sustainable energy technologies. Innovation is essential for driving broader adoption and reducing reliance on conventional energy sources.

Sound implementation of these principles maximizes the effectiveness and long-term sustainability of energy resources. Strategic planning and consistent execution are crucial for achieving meaningful reductions in carbon emissions and promoting a cleaner energy future.

The following section will delve into the specific policy implementations required to promote widespread adoption.

1. Solar irradiance intensity

Solar irradiance intensity, measured in watts per square meter (W/m), represents the power received from the sun per unit area. Its direct correlation to solar energy production establishes it as a critical factor affecting the viability of photovoltaic (PV) systems, a prominent component of the overarching solar energy approach. Higher irradiance levels translate directly into increased electricity generation by solar panels, making regions with consistent and high solar irradiance more economically favorable for solar energy installations. This dependence is crucial in evaluating the effectiveness and return on investment for solar energy projects.

Geographical variations in solar irradiance significantly impact the performance of solar farms and rooftop solar arrays. For instance, areas in desert regions typically experience higher irradiance levels compared to temperate zones, leading to greater energy yields from identical PV systems. Optimizing solar panel placement and orientation to maximize sunlight exposure based on the prevailing irradiance levels is a crucial design consideration. Technological advancements in solar cell materials and panel construction aim to improve energy conversion efficiency, further amplifying the impact of irradiance intensity on overall solar energy output.

In summary, the relationship between solar irradiance intensity and solar energy generation is fundamental. The availability of high irradiance levels dictates the economic feasibility and energy output potential of solar energy systems. Understanding and accurately assessing solar irradiance is crucial for effective planning, design, and deployment of renewable energy infrastructure and can drive technological advancements in solar energy conversion. Future challenges in solar energy involve developing ways to harness solar power in regions with less-than-optimal irradiance through the development of efficient systems and storage solutions.

2. Wind turbine efficiency

Wind turbine efficiency directly impacts the energy output of wind farms, a significant aspect of renewable energy infrastructure. This parameter determines how effectively wind turbines convert kinetic energy from the wind into electrical energy. An increase in wind turbine efficiency translates to a greater electricity yield from the same wind resource. For example, modern wind turbines achieve power coefficients, reflecting the fraction of wind energy captured, exceeding 50%, demonstrating significant improvements over earlier designs.

Understanding wind turbine efficiency is crucial for optimizing wind farm design and operation. Factors such as blade aerodynamics, generator technology, and control systems collectively influence overall efficiency. Blade design innovations, incorporating airfoil shapes and pitch control mechanisms, enhance energy capture across varying wind speeds. Advanced generator technologies, like direct-drive systems, minimize energy losses associated with gearboxes. Real-world examples include wind farms in Denmark and Germany, where consistent investment in efficient turbine technology has resulted in high energy production and substantial contributions to national electricity grids.

In conclusion, wind turbine efficiency is a critical determinant of the economic viability and environmental impact of wind energy. Enhancing efficiency reduces the land footprint required for wind farms and lowers the cost per kilowatt-hour of electricity generated. Ongoing research focuses on materials science, aerodynamic optimization, and smart grid integration to further boost wind turbine efficiency, paving the way for wider adoption of wind energy.

3. Hydroelectric dam capacity

Hydroelectric dam capacity, a quantifiable measure of the potential energy output from a hydroelectric facility, has a direct and profound connection to the feasibility and impact of such facilities within the framework of utilizing renewable energy. This capacity, typically expressed in megawatts (MW), represents the maximum power a dam can generate under ideal conditions, effectively defining the scale of its contribution to the electrical grid. The capacity of a hydroelectric dam determines its ability to meet energy demands, especially during peak consumption periods. For instance, the Three Gorges Dam in China, with its massive capacity, significantly contributes to the nation’s energy supply, illustrating the practical impact of high-capacity hydroelectric facilities on a large scale. Understanding the interplay between water availability, reservoir size, and turbine efficiency is crucial in accurately determining and managing hydroelectric capacity.

The relationship between hydroelectric dam capacity and renewable energy development extends to environmental and economic considerations. Constructing large dams with high capacity can provide substantial amounts of clean energy, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and their associated emissions. However, the environmental impacts, such as altering river ecosystems and displacing communities, must be carefully evaluated. Smaller-scale hydroelectric projects, often referred to as run-of-river systems, may have lower capacity but also minimize environmental disruption. The choice of dam size and capacity depends on a careful balancing of energy needs, environmental preservation, and economic viability. In Norway, a nation heavily reliant on hydroelectric power, the management and expansion of hydroelectric capacity are central to its energy policy, highlighting the real-world implications of strategic capacity planning.

Ultimately, hydroelectric dam capacity represents a critical factor in assessing the value and sustainability of hydroelectric power as a renewable energy source. Optimizing dam capacity requires considering both the potential for energy generation and the associated environmental and social impacts. Continual advancements in dam technology and water resource management offer opportunities to enhance capacity while minimizing adverse consequences. The integration of hydroelectric power into comprehensive energy plans necessitates a thorough understanding of dam capacity, its limitations, and its potential for contributing to a cleaner and more sustainable energy future.

4. Geothermal gradient depth

Geothermal gradient depth, referring to the rate at which the Earth’s temperature increases with depth, is a fundamental factor governing the accessibility and viability of geothermal energy, a vital component of sustainable energy. This gradient dictates the depth to which drilling is necessary to reach temperatures suitable for electricity generation or direct-use applications. Lower gradients necessitate deeper, more expensive drilling, thereby impacting project economics. High gradient regions, conversely, offer shallower, more cost-effective access to usable geothermal resources. The practical significance lies in understanding this relationship to strategically plan and implement geothermal energy projects in areas where resources are readily accessible.

The impact of geothermal gradient depth is evident in various global examples. Iceland, situated on a geologically active region with a high geothermal gradient, utilizes geothermal energy extensively for both electricity production and district heating. The shallow geothermal resources allow for relatively inexpensive access to high-temperature fluids, making geothermal energy a dominant component of the nation’s energy mix. In contrast, regions with lower gradients require enhanced geothermal systems (EGS), involving fracturing hot, dry rocks deep underground to create artificial reservoirs. These EGS projects, while expanding geothermal energy potential, are more technically challenging and capital-intensive. Understanding and mapping the geothermal gradient is crucial for resource assessment and technology selection.

In conclusion, geothermal gradient depth is a key determinant of the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of geothermal energy projects. Mapping and understanding geothermal gradients are essential for identifying suitable locations and selecting appropriate extraction technologies. Ongoing research and technological advancements focus on enhancing extraction methods, especially for areas with less favorable geothermal gradients, aiming to broaden the application of geothermal energy and contribute to a diversified and sustainable energy portfolio.

5. Biomass sustainable sourcing

Biomass sustainable sourcing constitutes a critical element in ensuring the long-term viability of biomass energy as a genuine renewable resource. The method by which biomass is obtained directly impacts its carbon footprint and ecological effects, thus influencing its role among sustainable energy options. Neglecting sustainable sourcing practices can negate the environmental benefits typically associated with biomass energy.

- Forest Management Practices

Sustainable forest management ensures that timber harvesting does not exceed the rate of forest regeneration. Practices include selective logging, replanting efforts, and protection of biodiversity within forest ecosystems. Certifications, such as those from the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), provide assurance that biomass sourced from forests adheres to environmental and social standards. Unregulated deforestation for biomass can lead to habitat loss, soil erosion, and increased carbon emissions, undermining the sustainability of biomass energy.

- Agricultural Residue Utilization

Agricultural residues, such as corn stover, wheat straw, and rice husks, represent a significant biomass resource. Sustainable utilization of these residues involves careful management to prevent soil degradation and nutrient depletion. Leaving a sufficient amount of residue on fields helps maintain soil fertility and prevent erosion. Over-harvesting of agricultural residues can lead to reduced crop yields and increased reliance on synthetic fertilizers, negatively impacting the sustainability of biomass energy.

- Dedicated Energy Crops

Dedicated energy crops, such as switchgrass, miscanthus, and short-rotation woody crops, are specifically grown for energy production. Sustainable cultivation of these crops requires careful consideration of land use, water management, and fertilizer inputs. Selecting native or naturalized species that require minimal inputs can enhance the sustainability of energy crop production. Monoculture cultivation of energy crops can lead to reduced biodiversity and increased susceptibility to pests and diseases, diminishing the environmental benefits of biomass energy.

- Waste Stream Management

Organic waste streams, including municipal solid waste, food waste, and wastewater treatment sludge, represent a valuable biomass resource. Sustainable management of these waste streams involves efficient collection, sorting, and processing to maximize energy recovery and minimize environmental impacts. Anaerobic digestion and gasification technologies can convert organic waste into biogas and other valuable products. Improper handling of organic waste can lead to greenhouse gas emissions and water pollution, detracting from the sustainability of biomass energy.

The examples above underscore the essential nature of sustainable practices in biomass utilization. Regardless of the specific type of biomass, ensuring responsible resource management is vital for the actualization of its potential as a carbon-neutral or carbon-negative energy source. Therefore, biomass must be procured with meticulous planning to avoid unintended environmental consequences.

6. Energy storage integration

Energy storage integration is critical for maximizing the utility and reliability of variable resources such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric power. These methods are subject to fluctuations in availability, making direct grid integration challenging. Efficient storage is essential for overcoming these limitations and enabling a more consistent energy supply.

- Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS)

Battery systems store excess electricity generated during peak production periods for later use when renewable energy sources are less productive. These systems are deployed at various scales, from residential installations paired with solar panels to large-scale grid stabilization projects. Lithium-ion batteries are frequently employed due to their high energy density and rapid response times. Examples include utility-scale batteries connected to wind farms in Texas, enhancing grid stability by providing immediate power reserves during wind lulls.

- Pumped Hydro Storage (PHS)

Pumped hydro involves pumping water uphill to a reservoir during periods of excess electricity generation, typically using renewable energy. This water is then released to generate electricity when demand is high or renewable sources are insufficient. PHS provides long-duration storage capabilities, making it suitable for balancing daily or weekly fluctuations in supply and demand. The Bath County Pumped Storage Station in Virginia represents a large-scale implementation, storing energy equivalent to many hours of operation.

- Thermal Energy Storage (TES)

Thermal energy storage systems store energy in the form of heat or cold. These systems can be integrated with concentrated solar power (CSP) plants to store thermal energy collected during daylight hours, allowing electricity generation to continue after sunset. TES can also be used in district heating and cooling systems, storing excess heat from industrial processes or solar thermal collectors. Molten salt storage technology, used in CSP plants in Spain, exemplifies TES’s capacity to extend the operational hours of renewable energy facilities.

- Hydrogen Energy Storage

Excess electricity from renewable energy sources can be used to produce hydrogen through electrolysis. This hydrogen can then be stored and used later in fuel cells to generate electricity, or directly as a fuel for transportation or industrial processes. While hydrogen storage technologies are still developing, they offer a potential pathway for long-duration, large-scale energy storage. Pilot projects in Australia explore using excess solar and wind power to produce hydrogen for export, demonstrating the potential for hydrogen to facilitate the integration of renewable energy on a global scale.

Effectively addressing the inherent variability of solar, wind, and hydroelectric power necessitates strategic integration of diverse storage solutions. BESS offers quick response times, PHS provides long-duration storage, TES extends the operational hours of solar thermal plants and hydrogen storage has the potential for very long duration storage. These technologies, when coupled with renewable energy facilities, contribute significantly to grid stability, reliability, and the overall transition to a more sustainable energy system.

7. Technological advancements

Technological advancements have demonstrably propelled the efficiency and economic viability of solar, wind, and hydroelectric power, constituting significant progress in renewable energy resources. For example, advancements in photovoltaic cell technology, such as the development of PERC (Passivated Emitter and Rear Contact) cells, have increased the efficiency of solar panels, enabling greater electricity generation from a given surface area. Similarly, innovations in wind turbine blade design and materials have led to turbines capable of capturing more wind energy and operating at higher capacity factors. Advancements in hydroelectric power encompass more efficient turbine designs and the development of pumped hydro storage, improving the flexibility and reliability of hydroelectric facilities. These improvements serve as a direct cause, with tangible effects on energy output, cost reduction, and the overall feasibility of each resource.

Specific instances further illustrate this connection. The evolution of thin-film solar cells has reduced material costs and expanded the applications of solar energy to flexible and lightweight surfaces. In wind energy, the introduction of taller towers and larger rotor diameters allows turbines to access stronger, more consistent winds at higher altitudes. Moreover, the integration of advanced control systems and predictive analytics enhances the operational efficiency of wind farms. In hydroelectricity, the development of fish-friendly turbine designs mitigates environmental impact while maintaining energy generation capabilities. These tailored improvements demonstrate that technological innovation is not merely incremental but fundamentally transformative, enabling renewable energy sources to compete more effectively with traditional fossil fuels.

In conclusion, technological advancements are not only crucial, but essential for the continued growth and widespread adoption of solar, wind, and hydroelectric power. Continued investment in research and development remains critical to address existing challenges, such as intermittency, grid integration, and cost competitiveness. These efforts contribute directly to a cleaner, more sustainable energy future, enhancing energy security and mitigating the impacts of climate change. By continuously pushing the boundaries of what is technologically possible, these energy sources become ever more efficient and cost-effective, thus driving the energy transition.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses prevalent inquiries regarding renewable energy options, providing detailed, objective responses to enhance understanding and dispel misconceptions.

Question 1: Are resources consistently available?

Availability is subject to environmental conditions. Solar output varies with daylight hours and cloud cover, while wind power depends on wind patterns. Hydroelectric generation relies on water availability, influenced by rainfall and snowmelt. Energy storage systems are crucial for mitigating fluctuations and ensuring consistent supply.

Question 2: Is widespread deployment economically viable?

The economic viability depends on factors such as technology costs, government incentives, and energy market dynamics. While initial investment costs can be significant, operational costs are typically lower than fossil fuel-based generation. Continued technological advancements and economies of scale are further reducing costs.

Question 3: Are these methods environmentally benign?

While these options generally have lower environmental impacts than fossil fuels, some impacts are inevitable. Large-scale hydroelectric projects can alter river ecosystems. Wind farms may pose risks to birds and bats. Biomass energy can contribute to deforestation if not sustainably sourced. Careful planning and mitigation measures are essential to minimize negative consequences.

Question 4: Can these methods meet global energy demands?

These resources possess the potential to meet a significant portion of global energy demands, but a diversified approach is necessary. No single source can provide a complete solution. Combining different sources, along with energy efficiency measures, is essential for transitioning to a sustainable energy system.

Question 5: What are the primary barriers to widespread adoption?

Key barriers include intermittency, infrastructure limitations, and regulatory hurdles. Energy storage technologies are needed to address intermittency. Grid infrastructure must be upgraded to accommodate distributed sources. Streamlined permitting processes and supportive policies can accelerate adoption.

Question 6: How can energy consumers contribute to expansion?

Energy consumers can contribute by adopting energy-efficient practices, supporting policies that promote development, and investing in distributed systems like rooftop solar panels. Consumer choices and behaviors play a crucial role in driving demand and shaping the energy landscape.

In conclusion, understanding both the potential and the challenges associated with these resources is critical for informed decision-making and effective energy planning.

The subsequent section examines policy implications for realizing the promise of a sustainable energy future.

Concluding Assessment

The preceding analysis elucidates the operational characteristics, inherent challenges, and developmental prospects associated with solar, wind, and hydroelectric power. These methods, while diverse in their technical attributes and environmental considerations, represent pivotal components in the transition toward a sustainable energy infrastructure. The successful integration of these technologies necessitates comprehensive planning, sustained innovation, and pragmatic policy implementations.

Continued investment in these domains, coupled with a commitment to responsible resource management, will dictate the extent to which a decarbonized energy future can be realized. The sustained advancement and conscientious deployment of these approaches are essential to mitigate global environmental concerns and establish a more secure and resilient energy landscape for future generations.