Fossil fuels, nuclear energy, and certain mineral resources constitute a crucial category of energy and material sources. These substances are characterized by their finite nature; their formation processes typically require geological timescales far exceeding human lifespans. Consequently, once depleted, they cannot be replenished within a relevant timeframe.

The utilization of these resources has historically fueled industrialization and technological advancement, providing concentrated forms of energy and raw materials for various applications. However, their extraction and combustion are frequently associated with environmental consequences, including greenhouse gas emissions and habitat disruption. Furthermore, geopolitical considerations often arise due to the uneven distribution of these resources across the globe.

This discourse will focus on three principal representatives of this resource category: coal, petroleum, and natural gas. Each possesses unique characteristics regarding their formation, extraction methods, applications, and environmental impacts, demanding individual scrutiny.

Strategies for Resource Management

Effective management of these sources necessitates a multifaceted approach, incorporating responsible consumption, technological innovation, and regulatory frameworks.

Tip 1: Optimize Energy Efficiency: Implement strategies to minimize energy consumption across all sectors. This includes utilizing energy-efficient appliances, improving building insulation, and promoting efficient transportation systems.

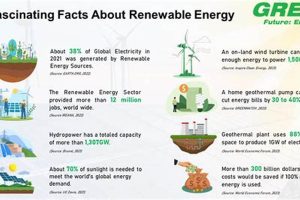

Tip 2: Diversify Energy Sources: Reduce reliance on any single source by developing a diverse energy portfolio that incorporates renewable alternatives. This mitigates risks associated with price volatility and resource depletion.

Tip 3: Invest in Carbon Capture Technologies: Explore and deploy technologies capable of capturing carbon dioxide emissions from industrial processes and power plants. This can help mitigate the environmental impact of combustion.

Tip 4: Promote Circular Economy Principles: Encourage the reuse, recycling, and remanufacturing of materials to reduce the demand for raw resource extraction. This extends the lifespan of existing materials and minimizes waste.

Tip 5: Establish Regulatory Frameworks: Implement clear and enforceable regulations to govern resource extraction, consumption, and disposal. This ensures responsible practices and minimizes environmental damage.

Tip 6: Support Research and Development: Invest in research and development to discover new extraction methods, improved energy storage solutions, and innovative material substitutes. Technological advancements are crucial for sustainable resource management.

Tip 7: Improve infrastructure to minimize waste: Develop and maintain infrastructure to minimize waste and improve efficiency such as pipelines, electrical grids, and public transportation.

Adopting these strategies will contribute to a more sustainable and secure resource future, minimizing the negative impacts associated with their utilization.

The following section will provide concluding remarks on the broader implications of these resources.

1. Fossil fuel origin

The origin of fossil fuels is intrinsically linked to the categorization of coal, petroleum, and natural gas as resource of finite quantities. These fuels are derived from the remains of prehistoric organic matter, specifically plants and animals that lived millions of years ago. Over geological timescales, these organic materials underwent transformation under immense pressure and heat within the Earth’s crust. This process converted the organic matter into carbon-rich substances that are now exploited for their energy content. For example, coal is primarily formed from ancient plant matter in swampy environments, while petroleum and natural gas originate from marine organisms deposited on the ocean floor. This slow, geological formation process is the primary reason why these resources are classified as it is; their rate of replenishment is negligible compared to the rate of human consumption.

The understanding of origin is crucial for several reasons. First, it highlights the finite nature of these resources. Because they require millions of years to form, their extraction represents a net reduction in the Earth’s stock of these fuels. Second, the method of extraction often poses environmental challenges, including habitat destruction and potential contamination of ecosystems. For example, the extraction of oil from tar sands requires significant energy input and can result in substantial land disturbance. Third, the distribution of fossil fuel deposits influences global geopolitics, as nations with significant reserves wield considerable economic and political power. Instances of international conflicts over access to petroleum illustrate this point.

In conclusion, the origin of fossil fuels is a defining characteristic that establishes their classification as non-renewable. The understanding of this origin informs responsible resource management and underscores the need for a transition to alternative, sustainable energy sources. Failure to recognize and act upon this connection will have significant implications for future generations, leading to resource depletion, environmental degradation, and potential geopolitical instability.

2. Nuclear energy source

Nuclear energy, as a source, critically links to the discourse on finite resources. Its classification stems from its reliance on uranium, a naturally occurring element extracted from the Earth’s crust. While uranium is relatively abundant compared to other fissionable materials, its reserves are nonetheless finite and subject to depletion. The utilization of uranium in nuclear reactors involves a controlled nuclear fission process, releasing substantial energy in the form of heat, which is then used to generate electricity. The energy obtained is substantial, but the uranium, once consumed in the fission process, is converted into radioactive waste, rendering it unusable as a fuel source in the current generation of reactors. The spent nuclear fuel presents a significant long-term waste management challenge. For instance, the spent fuel from nuclear power plants must be stored for thousands of years to allow for the radioactive decay of certain isotopes. This necessity for long-term storage underscores the finite nature of the resource and the inherent limitations of nuclear power as a sustainable energy solution in the traditional sense.

Consider the example of Canada, which possesses significant uranium reserves. While it is a major exporter of uranium, these reserves are not inexhaustible. Continued extraction will eventually lead to depletion. The ongoing debate regarding the expansion of nuclear power worldwide is therefore inextricably linked to the question of uranium availability and the environmental impacts of its extraction and processing. Furthermore, the potential for nuclear accidents, such as the Chernobyl and Fukushima disasters, highlights the inherent risks associated with this energy source, reinforcing the need for stringent safety regulations and responsible resource management. Furthermore, extraction process can potentially harm nature by leaving toxic waste in nearby soil and bodies of water.

In summary, while nuclear energy offers a significant source of power and reduces reliance on fossil fuels, its dependency on uranium, a finite resource, and the challenges of managing radioactive waste, firmly place it within the framework of a limited resource. A comprehensive understanding of its role necessitates consideration of uranium availability, extraction impacts, waste management strategies, and inherent safety risks, all of which contribute to a more balanced and informed assessment of its potential as a viable component of the future energy landscape. Because of this it is one of the main 3 types of a non renewable resource.

3. Mineral resource scarcity

Mineral resource scarcity is a critical element in the classification of certain materials as resources of finite availability. While not all minerals are energy sources like coal or petroleum, specific minerals are essential for industrial processes, technological applications, and energy infrastructure, thereby influencing energy production and consumption. This scarcity arises from the geological rarity of certain minerals, coupled with the challenges and environmental impacts associated with their extraction. The extraction of these resources will also impact and potentially harm our planet as well.

Consider, for example, rare earth elements, a group of seventeen metallic elements vital for manufacturing components for electronics, renewable energy technologies (wind turbines and solar panels), and electric vehicles. The geographical concentration of rare earth element deposits, primarily in China, creates geopolitical dependencies and concerns regarding supply chain security. The mining and processing of these elements also involve significant environmental risks, including water pollution and radioactive waste generation. The scarcity of these elements, coupled with the associated extraction challenges, underscores the need for responsible resource management, including recycling and the development of alternative materials. Moreover, minerals like lithium and cobalt, essential for battery production in electric vehicles, face increasing demand as the world transitions towards electrification. The limited availability and uneven distribution of these minerals pose potential constraints on the widespread adoption of electric vehicles and the achievement of climate goals. It is important to consider these factors to ensure that these are carefully extracted from the earth without harming the environment as well.

In conclusion, mineral resource scarcity significantly impacts the assessment of resources of finite availability, particularly those minerals crucial for energy production, technological advancements, and climate change mitigation strategies. Addressing this scarcity requires a multi-pronged approach, including promoting circular economy principles, investing in material science research to discover substitute materials, and establishing responsible mining practices to minimize environmental impacts. Failure to address this aspect of resource scarcity will hinder sustainable development efforts and exacerbate resource dependencies.

4. Environmental consequences

The exploitation of fossil fuels, nuclear energy, and mineral resources is inextricably linked to adverse environmental outcomes. The extraction, processing, transportation, and utilization of these resources generate a range of environmental impacts, encompassing air and water pollution, habitat destruction, greenhouse gas emissions, and radioactive waste accumulation. The combustion of coal, petroleum, and natural gas releases substantial quantities of carbon dioxide, a primary greenhouse gas contributing to global climate change. Air pollutants, such as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, released during fossil fuel combustion contribute to acid rain and respiratory problems. For example, the burning of coal in power plants has been associated with increased rates of asthma and other respiratory illnesses in nearby communities. The extraction of petroleum through methods like hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, can lead to groundwater contamination and increased seismic activity.

Nuclear power generation, while emitting minimal greenhouse gases during operation, presents the challenge of managing radioactive waste. This waste requires long-term storage solutions to prevent environmental contamination. Moreover, the potential for nuclear accidents, exemplified by Chernobyl and Fukushima, underscores the catastrophic environmental and human health consequences associated with nuclear power. Mineral extraction, essential for various industrial processes, often results in habitat destruction, soil erosion, and water pollution. Mining operations can release heavy metals and other toxic substances into the environment, contaminating water sources and posing risks to human and ecological health. The extraction of rare earth elements, crucial for renewable energy technologies and electronics, poses significant environmental challenges due to the toxic chemicals used in processing.

Addressing the environmental consequences of using non-renewable resources is crucial for sustainable development. Mitigation strategies include transitioning to renewable energy sources, implementing stricter environmental regulations, investing in carbon capture technologies, and promoting responsible resource management practices. A comprehensive understanding of the environmental impacts associated with the extraction and use of these is essential for informing policy decisions and promoting a more sustainable future. Without such an understanding, environmental degradation will continue, exacerbating climate change, impacting human health, and threatening ecological integrity.

5. Geopolitical Implications

The distribution, control, and access to critical energy and mineral commodities exert substantial influence on international relations, national security, and global economic dynamics. This influence arises from the inherent reliance of industrialized societies on these resources for energy generation, industrial production, and technological advancement.

- Resource Control and National Power

Nations possessing significant reserves of fossil fuels, uranium, or strategic minerals often wield considerable geopolitical leverage. Control over these resources can translate into economic power, enabling countries to influence global markets, negotiate favorable trade agreements, and project military strength. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) serves as a prime example, demonstrating how collective control over oil production can significantly impact global energy prices and exert influence on international policy.

- Supply Chain Vulnerabilities and Security Concerns

The concentration of resource production in specific regions can create supply chain vulnerabilities, making nations dependent on potentially unstable or adversarial countries. Dependence on foreign sources for critical minerals or energy can expose countries to economic coercion or supply disruptions in times of geopolitical tension. Securing access to vital resources through diplomatic alliances, military presence, or infrastructure development becomes a strategic imperative for many nations. Examples include China’s dominance in rare earth element production and the strategic importance of maritime routes for oil transportation.

- Resource Competition and International Conflict

Competition for access to scarce resources can escalate into international disputes or even armed conflicts. Territorial claims in resource-rich regions, disputes over maritime boundaries, and competition for control over pipelines can fuel tensions between nations. The South China Sea, with its disputed territorial claims and potential oil and gas reserves, exemplifies how resource competition can exacerbate geopolitical rivalries. The scramble for resources in Africa has also been linked to conflicts and instability in several countries.

- Energy Transitions and Shifting Power Dynamics

The global transition towards renewable energy sources has the potential to reshape geopolitical power dynamics. As countries invest in renewable energy technologies and reduce their dependence on fossil fuels, their reliance on traditional resource-rich nations may diminish. This shift could lead to a redistribution of power, with countries possessing technological expertise and renewable energy resources gaining greater influence. However, the transition may also create new dependencies on minerals required for renewable energy technologies, potentially shifting geopolitical competition to different resource domains.

The geopolitical implications associated with finite resources are complex and multifaceted, influencing international relations, national security, and global economic stability. A comprehensive understanding of these implications is crucial for policymakers, businesses, and citizens to navigate the challenges and opportunities arising from the ongoing transformation of the global energy landscape and resource economy.

6. Limited resource lifespan

The concept of a limited resource lifespan is intrinsic to the definition of these resources. Coal, petroleum, natural gas, uranium, and certain critical minerals are classified as non-renewable precisely because their rate of formation or replenishment is far slower than their rate of consumption. This disparity between supply and demand ultimately dictates a finite existence for these resources, irrespective of the magnitude of initial reserves. The lifespan represents the estimated period until economically viable extraction becomes impossible or until reserves are depleted to a level where their contribution to energy or material needs becomes insignificant. The lifespan of coal, for instance, is projected to be longer than that of petroleum due to its relatively larger global reserves. However, even coal’s lifespan is limited, and its continued use at current rates presents long-term sustainability challenges. The finite nature stems from their geological formation processes which take geological time scales. The lifespan is limited and finite. The use of technology may prolong the access to this resource but does not provide any type of way to make the resource sustainable.

The importance of understanding the limited lifespan is multi-faceted. Firstly, it necessitates strategic planning for energy diversification and the development of renewable energy alternatives. A failure to transition to sustainable sources before the depletion of fossil fuels could lead to energy shortages, economic instability, and geopolitical conflicts. Secondly, it encourages responsible resource management, promoting efficient extraction techniques, minimizing waste, and fostering recycling efforts to extend the lifespan of existing reserves. Thirdly, it informs policy decisions regarding carbon emissions, environmental regulations, and international cooperation to mitigate the impacts of climate change and resource depletion. The depletion of high-grade ore deposits, for example, forces the extraction of lower-grade ores, resulting in increased energy consumption and environmental degradation. This scenario highlights the practical significance of considering the lifespan aspect when evaluating the overall sustainability of utilizing mineral resources.

In summary, the limited lifespan is a defining attribute which underscores the urgency of transitioning to sustainable energy and material sources. It necessitates a proactive approach encompassing responsible resource management, technological innovation, and policy frameworks aimed at mitigating the risks associated with resource depletion. Addressing the challenges posed by the finite nature of these resources is essential for ensuring long-term energy security, environmental sustainability, and global economic stability. As supplies begin to dwindle for each of the three main non-renewable resources, it is important to find alternative resources or else civilization as we know it could collapse.

Frequently Asked Questions About Primary Sources

The following addresses common inquiries related to this topic, clarifying prevalent misconceptions and providing concise answers.

Question 1: How can the lifespan of a non-renewable resource be extended?

Resource lifespans can be extended through a combination of strategies. These include improving extraction efficiency to minimize waste, promoting recycling and reuse of materials, and developing alternative materials or technologies that reduce demand for the resource. Technological advancements enabling the extraction of previously inaccessible reserves can also contribute. Consumption patterns also play a factor. If populations practice proper waste management then the amount of non renewable resources can be used at a sustainable rate.

Question 2: Are non-renewable resources evenly distributed across the globe?

No, these resources are not uniformly distributed. Geological processes have concentrated specific resources in particular regions, leading to uneven distribution patterns. This uneven distribution creates geopolitical dependencies and influences international trade relations. This further establishes the need for a non reliance on a specific resource.

Question 3: What are the main environmental consequences associated with the usage of non-renewable resources?

The main environmental impacts include air and water pollution from extraction and processing, greenhouse gas emissions from combustion, habitat destruction due to mining activities, and the generation of hazardous waste. These consequences can have far-reaching effects on ecosystems and human health.

Question 4: How do the economic costs of renewable resources compare to those of non-renewable resources?

The economic costs are evolving. While the initial investment costs for renewable energy technologies can be higher, the long-term operational costs are often lower due to the absence of fuel expenses. As technology advances and economies of scale are achieved, renewable energy sources are becoming increasingly competitive with non-renewable sources.

Question 5: What role does government regulation play in the management of non-renewable resources?

Government regulation plays a crucial role in ensuring responsible resource management. Regulations can govern extraction practices, set emission standards, promote energy efficiency, and encourage the development of renewable energy sources. Effective regulation can mitigate environmental impacts and promote sustainable resource utilization.

Question 6: What are some examples of mineral resources that face scarcity issues?

Examples include rare earth elements, lithium, cobalt, and platinum group metals. These minerals are essential for various technologies, including electronics, electric vehicles, and renewable energy systems. Their limited availability and uneven distribution raise concerns about supply chain security and potential bottlenecks in technological development. These factors should always be weighed before making the decision to invest in one of these non-renewable resources.

This FAQ section provides a concise overview of essential information related to the topic of non-renewable resources. Further sections will delve into specific case studies and emerging trends in resource management.

The subsequent section will explore in detail different solutions and practices to mitigate the use of non-renewable resources.

Conclusion

This exploration of what are 3 types of non renewable resources has illuminated their origin, implications, and challenges. The finite nature of fossil fuels, nuclear energy sources, and specific minerals presents a pressing need for responsible stewardship and strategic planning. Environmental consequences, geopolitical considerations, and the limited lifespan of these commodities necessitate a shift towards sustainability.

Addressing the complex issues surrounding these necessitates a multifaceted approach encompassing technological innovation, policy reform, and global collaboration. Transitioning to renewable energy sources, promoting circular economy principles, and adopting responsible consumption patterns are essential steps toward mitigating the risks associated with dependence. The future hinges on collective action to secure a sustainable energy future and environmental integrity.