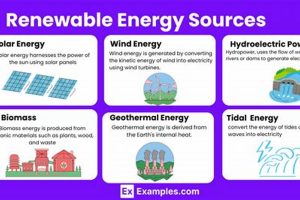

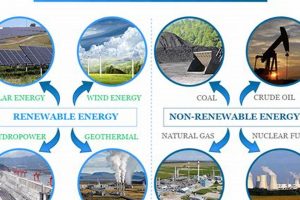

Renewable resources are natural assets that replenish over time through natural processes, essentially at a rate comparable to their consumption. Solar energy, derived from the sun, exemplifies a renewable source as its availability is continuous and predictable. Wind power, harnessed by turbines, represents another renewable option due to the ongoing atmospheric circulation. Conversely, non-renewable resources are finite substances that exist in limited quantities on Earth and cannot be replaced within a human timescale. Fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, are prime instances of non-renewable resources, formed over millions of years from decayed organic matter.

The utilization of renewable sources offers substantial environmental advantages, including reduced greenhouse gas emissions and diminished air and water pollution compared to reliance on finite stores. Historically, human societies have depended on both types of resources. However, the increasing awareness of the environmental impact associated with the extraction and combustion of finite reserves has spurred a global shift towards sustainable, replenishable supplies. This transition is driven by concerns regarding climate change, resource depletion, and the need for long-term energy security.

The subsequent sections will delve into specific types of both replenishable and finite options. The discussion includes the technologies employed to harness each and the geographical distribution of these resources. Finally, consideration is given to the economic and political implications associated with both sets of natural endowments, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between resource availability, technological innovation, and societal development.

Resource Management Strategies

Effective resource management is crucial for a sustainable future, balancing human needs with the preservation of the environment. The following strategies offer guidance on navigating the complexities of resource consumption and conservation.

Tip 1: Prioritize Renewable Energy Investments: Direct capital towards renewable energy infrastructure, such as solar farms, wind turbines, and geothermal plants. This reduces reliance on finite reserves and promotes energy independence.

Tip 2: Enhance Energy Efficiency: Implement energy-efficient technologies in buildings, transportation, and industrial processes. This minimizes overall energy demand, conserving both replenishable and finite sources.

Tip 3: Develop Sustainable Extraction Practices: For finite stores, adopt extraction methods that minimize environmental damage, reduce waste, and reclaim disturbed land. This ensures resource availability for future generations.

Tip 4: Promote Circular Economy Principles: Emphasize recycling, reuse, and repair to extend the lifespan of products and reduce the need for new resource extraction. A circular economy minimizes waste and conserves valuable materials.

Tip 5: Implement Carbon Capture and Storage Technologies: Invest in technologies that capture carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel combustion and store them underground. This mitigates the environmental impact of finite options during the transition to renewables.

Tip 6: Encourage Sustainable Consumption Patterns: Educate consumers about the environmental impact of their purchasing decisions and promote responsible consumption habits. Informed choices can drive demand for sustainable products and practices.

Tip 7: Support Research and Development: Fund research into innovative renewable energy technologies, improved extraction methods, and resource management strategies. Continuous innovation is essential for addressing the challenges of resource scarcity and environmental sustainability.

Implementing these strategies fosters a more sustainable future, reducing dependence on limited reserves while safeguarding environmental integrity. By focusing on both efficient utilization and the development of replenishable substitutes, societies can ensure long-term resource security and ecological well-being.

The following sections will explore the long-term implications of resource management and the path to a truly sustainable economy.

1. Solar radiation (Renewable)

Solar radiation, a perpetually available energy source from the sun, stands as a cornerstone in the discussion of replenishable and finite natural assets. It exemplifies a clean, abundant alternative to the limited reserves of fossil fuels, offering a pathway toward sustainable energy solutions.

- Energy Generation

Solar radiation can be converted into electricity through photovoltaic (PV) cells or concentrated solar power (CSP) systems. PV cells directly convert sunlight into electricity, while CSP systems use mirrors or lenses to focus sunlight onto a receiver, heating a fluid that drives a turbine to generate electricity. This energy can power homes, businesses, and even entire cities, significantly reducing the reliance on finite sources.

- Environmental Impact

Unlike the extraction and combustion of fossil fuels, solar power generation produces minimal greenhouse gas emissions. Solar facilities require land, and manufacturing PV panels can have environmental effects, but these impacts are substantially lower compared to the lifecycle emissions associated with finite fuels. The widespread adoption of solar energy contributes to mitigating climate change and improving air quality.

- Economic Considerations

The initial investment for solar energy infrastructure can be significant, but operational costs are relatively low due to the absence of fuel expenses. As technology advances and production scales up, the cost of solar energy has decreased dramatically, making it increasingly competitive with conventional energy sources. Government incentives and policies further promote the economic viability of solar power.

- Global Accessibility

Solar radiation is available worldwide, although its intensity varies by location and time of year. Regions with high solar irradiance, such as deserts and sunny climates, are particularly well-suited for solar energy generation. Even areas with less direct sunlight can effectively utilize solar technologies. The decentralization of solar power also enhances energy security and independence, especially in remote or underserved communities.

These aspects illustrate the pivotal role of solar radiation as a viable alternative to exhaustible options. By understanding its potential, limitations, and economic feasibility, societies can make informed decisions about transitioning to a more sustainable energy future, ultimately reducing dependence on finite reserves and mitigating environmental degradation.

2. Fossil fuels (Non-Renewable)

Fossil fuels, comprising coal, oil, and natural gas, are central to understanding finite natural endowments and their contrast with replenishable options. Formed over millions of years from decayed organic matter subjected to intense heat and pressure, these fuels exist in limited quantities and cannot be replenished within a human timescale. Their role in energy production underscores the distinction between finite and replenishable resources, as the extraction and combustion of fossil fuels contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions and environmental degradation, unlike solar radiation and other sources that regenerate naturally.

The utilization of fossil fuels has historically driven industrial development and economic growth, but at a substantial environmental cost. For example, the burning of coal for electricity generation releases pollutants into the atmosphere, contributing to acid rain and respiratory problems. Similarly, the extraction of oil can lead to oil spills and habitat destruction, impacting marine ecosystems. Recognizing these consequences necessitates a transition towards sustainable, renewable alternatives to mitigate environmental damage and ensure resource security for future generations. Technologies aimed at carbon capture and storage seek to ameliorate the effects of fossil fuel use; however, they do not address the fundamental issue of depletion.

In conclusion, the understanding of finite fuels as a component is crucial for informing energy policies and promoting investments in replenishable resources. The challenges associated with extraction and consumption underscore the need for a transition towards alternatives that offer long-term sustainability and environmental protection. As technology advances and societal awareness grows, the shift towards renewable energies becomes increasingly imperative, mitigating the depletion of finite stores and addressing climate change.

3. Sustainability implications

The choice between replenishable and finite options carries profound consequences for long-term ecological health, economic stability, and societal well-being. Considering the sustainability implications within the context of resource utilization provides a framework for evaluating environmental impact, resource availability, and intergenerational equity.

- Environmental Degradation Mitigation

The utilization of replenishable natural assets minimizes pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and habitat destruction compared to finite sources. Solar, wind, and hydro power generate electricity without emitting pollutants, unlike coal-fired power plants. Conversely, the extraction and combustion of finite fuels lead to air and water pollution, climate change, and biodiversity loss. The transition towards renewable sources directly mitigates these adverse environmental impacts, fostering a more sustainable planet.

- Resource Depletion Avoidance

Finite sources are inherently limited, and their extraction leads to eventual depletion. Continued reliance on these sources jeopardizes future resource availability and creates economic instability. Replenishable resources, by definition, are continuously regenerated, ensuring long-term availability and reducing the risk of resource scarcity. Sustainable resource management practices prioritize the use of renewable options to avoid depletion and secure resource access for future generations.

- Climate Change Mitigation

The combustion of finite fuels is the primary driver of climate change, contributing to rising global temperatures, sea-level rise, and extreme weather events. Replenishable energy sources offer a pathway to decarbonize the energy sector and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Transitioning towards clean energy sources, such as solar and wind power, is essential for mitigating the adverse effects of climate change and achieving global climate goals.

- Economic Viability and Energy Security

Investing in replenishable energy technologies can stimulate economic growth, create jobs, and enhance energy security. While the initial capital investment may be higher, the long-term operational costs are often lower due to the absence of fuel expenses. Furthermore, the decentralization of replenishable energy production can reduce dependence on centralized power grids and enhance energy security, particularly in remote and underserved communities.

These facets highlight the critical link between resource choices and sustainability outcomes. Prioritizing replenishable resources fosters environmental protection, resource security, and economic stability, contributing to a more sustainable future. As societies grapple with the challenges of climate change and resource scarcity, the transition towards sustainable energy solutions becomes increasingly imperative, ensuring a habitable planet for generations to come.

4. Depletion Rate

The depletion rate serves as a critical metric in evaluating the sustainability of resource utilization, particularly when contrasting replenishable and finite resources. It quantifies the speed at which a resource is consumed relative to its rate of regeneration (for replenishable resources) or its total available stock (for finite resources), providing insights into the long-term viability of current consumption patterns.

- Quantifying Consumption vs. Regeneration

For replenishable assets, the depletion rate measures whether the rate of consumption exceeds the rate at which the resource naturally regenerates. If, for instance, deforestation occurs at a pace faster than reforestation, the depletion rate for forest resources is unsustainable. This imbalance leads to diminished biodiversity, soil erosion, and disrupted ecosystems, hindering the long-term availability of timber, carbon sequestration, and other ecological services.

- Exhaustion of Finite Reserves

With finite stores, such as fossil fuels, the depletion rate directly indicates how quickly the reserves are being exhausted. The current global consumption of oil, for example, is significantly higher than the rate at which it is naturally formed (essentially zero on a human timescale). This unsustainable depletion rate necessitates exploration for new reserves, increased efficiency in resource utilization, and the development of alternative energy sources to avert a future energy crisis.

- Economic Implications of Depletion

The depletion rate profoundly affects economic stability and resource prices. As easily accessible reserves of finite resources diminish, extraction costs increase, leading to higher prices for consumers and businesses. For instance, declining ore grades in mineral mines result in increased energy consumption and processing costs, making resource extraction less economically viable. In contrast, managing replenishable resources sustainably can create long-term economic opportunities, such as ecotourism and sustainable agriculture.

- Technological Influence on Depletion

Technological advancements can either accelerate or decelerate the depletion rate, depending on their application. Enhanced extraction technologies may allow for access to previously unreachable reserves, but can also exacerbate environmental damage. Conversely, innovations in energy efficiency, renewable energy generation, and resource recycling can reduce the reliance on finite sources and lower the depletion rate, promoting sustainable resource management.

Understanding and managing the depletion rate is paramount for fostering a sustainable future. By promoting conservation, investing in renewable alternatives, and adopting responsible consumption patterns, societies can mitigate the environmental and economic risks associated with resource depletion. The careful consideration of the depletion rate facilitates informed decision-making, ensuring the availability of resources for current and future generations.

5. Environmental consequences

The environmental consequences associated with differing classes of natural assets replenishable versus finite represent a core consideration in resource management and ecological sustainability. The use of fossil fuels, such as coal and oil, exemplifies finite resources whose extraction and combustion result in significant environmental impacts. These include greenhouse gas emissions contributing to climate change, air and water pollution harming ecosystems and human health, and habitat destruction from extraction processes. Conversely, the utilization of solar radiation and wind power, as replenishable options, minimizes these adverse effects. These sources generate electricity with considerably lower emissions and reduce the need for habitat-disrupting extraction activities. Therefore, environmental outcomes function as a crucial differentiating factor between the two classes of natural stores, influencing policies aimed at promoting sustainable energy transitions.

The practical significance of understanding these diverging environmental outcomes becomes evident in regulatory frameworks and investment decisions. Government policies, such as carbon pricing and renewable energy mandates, are designed to internalize the environmental costs associated with finite fuel usage, thereby incentivizing the adoption of cleaner, replenishable alternatives. Investment strategies increasingly favor businesses and projects that minimize environmental impact, reflecting a growing awareness of the financial risks associated with environmentally unsustainable practices. Real-world examples, such as the implementation of large-scale solar farms and wind energy projects, illustrate the feasibility and environmental benefits of transitioning away from a reliance on finite reserves.

In conclusion, the environmental consequences directly link resource type to ecological health, climate stability, and human well-being. While finite resources offer concentrated energy potential, their associated environmental costs necessitate a shift towards replenishable options. The challenges lie in scaling up renewable energy infrastructure, addressing intermittency issues, and ensuring equitable access to sustainable energy solutions. Recognizing and mitigating the environmental implications of resource choices remains paramount for fostering a sustainable and resilient future.

6. Technological advancements

Technological advancements exert a profound influence on both replenishable and finite natural assets, impacting extraction, utilization, and overall sustainability. In the realm of fossil fuels, technological innovations have enhanced extraction methods, enabling access to previously inaccessible reserves through techniques like hydraulic fracturing and deep-sea drilling. While these advancements increase the available supply, they also carry significant environmental risks, including habitat destruction, water contamination, and increased greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, technological progress in combustion efficiency has improved the energy output per unit of fuel consumed, yet this does not negate the finite nature of these resources or eliminate their environmental impact. For example, the development of more efficient gas turbines has increased power plant output while lowering fuel consumption, but the core reliance on a finite resource remains.

Conversely, technological innovations play a pivotal role in the development and deployment of replenishable energy technologies. Advancements in solar panel efficiency, wind turbine design, and energy storage systems have dramatically improved the viability and cost-effectiveness of renewable energy sources. Innovations such as perovskite solar cells and floating offshore wind turbines promise higher energy yields and expanded deployment opportunities. Smart grids, enabled by advanced communication and control technologies, facilitate the integration of intermittent renewable energy sources into the power grid, enhancing grid stability and reliability. These advancements directly address the challenges associated with the widespread adoption of sustainable energy systems.

In summary, technological advancements act as a double-edged sword, enhancing both the accessibility and utilization of finite stores while simultaneously driving the development of sustainable, replenishable alternatives. The key lies in directing technological progress towards solutions that minimize environmental impact, promote resource efficiency, and ensure a sustainable energy future. Policies supporting research and development in clean energy technologies, coupled with regulations that incentivize sustainable practices, can steer technological innovation towards outcomes that benefit both the environment and society.

7. Economic viability

Economic viability serves as a central determinant in the selection and deployment of both replenishable and finite natural endowments. The cost-effectiveness, investment returns, and market competitiveness of different energy sources significantly influence energy policies, business decisions, and consumer choices. Evaluating economic feasibility within the context of both categories is crucial for achieving a sustainable energy transition.

- Initial Investment Costs

Replenishable energy projects often entail high initial capital expenditures for infrastructure development, such as solar farms, wind turbine installations, and hydropower facilities. Conversely, the extraction and processing of finite fuels may require lower upfront investments, particularly when utilizing existing infrastructure. The higher initial costs of renewable projects can pose a barrier to entry, despite potentially lower long-term operating expenses. Government incentives, such as tax credits and subsidies, can help level the playing field by reducing the financial burden of initial investment.

- Operational and Maintenance Expenses

Replenishable assets typically exhibit lower operational and maintenance costs compared to finite energy systems. Solar and wind power, for instance, have minimal fuel expenses and reduced maintenance requirements, leading to cost savings over the project’s lifecycle. Finite fuel power plants, however, incur ongoing fuel costs, which fluctuate with market prices and geopolitical events. Furthermore, the maintenance and repair of aging fossil fuel infrastructure can be costly and unpredictable, impacting the overall economic viability.

- Market Competitiveness and Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE)

The economic competitiveness of different energy sources is often assessed using the levelized cost of energy (LCOE), which calculates the total cost of building and operating a power plant over its lifetime divided by the total electricity generated. The LCOE of renewable energy technologies has declined dramatically in recent years, making them increasingly competitive with conventional sources. In many regions, solar and wind power are now cheaper than new coal-fired power plants, driving a shift towards cleaner energy options. This enhanced market competitiveness is essential for accelerating the transition towards a sustainable energy system.

- Externalities and Social Costs

Economic viability assessments must also account for externalities, such as environmental pollution, health impacts, and climate change. Finite fuel consumption generates substantial social costs due to air and water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and resource depletion. These costs are often not fully reflected in market prices, leading to an undervaluation of the true economic impact. Replenishable energy sources produce fewer externalities, reducing the burden on society and promoting long-term sustainability. Incorporating these external costs into economic analyses can provide a more accurate assessment of the overall economic viability of different energy options.

In summary, economic viability serves as a critical driver in the adoption and deployment of both replenishable and finite options. As replenishable energy technologies become more cost-competitive and the social costs of finite fuel consumption are increasingly recognized, the economic case for a sustainable energy transition becomes more compelling. Factors such as initial investment costs, operational expenses, market competitiveness, and externalities must be carefully considered to ensure that energy policies and investment decisions promote both economic prosperity and environmental sustainability.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding replenishable and finite natural stores, offering insights to foster a deeper understanding of resource management and sustainable practices.

Question 1: What fundamentally differentiates a replenishable natural endowment from a finite one?

Replenishable resources regenerate naturally within a human timescale, while finite options exist in fixed quantities, depleting with use and lacking the capacity for substantial natural replenishment.

Question 2: Provide specific examples of widely utilized replenishable and finite natural resources.

Solar radiation, wind, hydroelectric power, and biomass constitute common replenishable resources. Conversely, coal, petroleum, natural gas, and uranium exemplify heavily utilized finite resources.

Question 3: How does the utilization of replenishable and finite resources impact environmental sustainability?

Replenishable sources generally present lower environmental impacts, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and pollution. Finite fuel extraction and combustion, conversely, contribute significantly to environmental degradation and climate change.

Question 4: What are the long-term economic implications of relying on either replenishable or finite resources?

Reliance on finite options may lead to price volatility and resource scarcity as reserves dwindle. Investing in replenishable infrastructures fosters long-term economic stability and energy independence, though initial capital investments may be substantial.

Question 5: What role does technological innovation play in the sustainability of both replenishable and finite resource utilization?

Technological advancements enhance the efficiency and accessibility of replenishable energies, reducing reliance on finite stocks. Conversely, technological innovations in finite resource extraction may exacerbate environmental consequences.

Question 6: How can societies effectively manage resources to ensure long-term sustainability and minimize environmental harm?

Sustainable resource management involves promoting energy efficiency, investing in replenishable energy, implementing conservation measures, and adopting circular economy principles to minimize waste and environmental impact.

Understanding these fundamental questions fosters informed decision-making in resource utilization, promoting a balanced approach to meet present needs without compromising future generations’ access to essential resources.

The subsequent section will explore policy frameworks that promote sustainable resource management and incentivize the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Conclusion

The preceding analysis illustrates the critical distinction between replenishable and finite natural resources. The examples of solar and wind power, versus coal and oil, underscore the divergent paths societies can pursue in meeting energy demands. A comprehensive evaluation encompassing environmental impact, economic viability, and long-term sustainability necessitates a strategic shift toward the widespread adoption of replenishable alternatives.

Effective resource management requires a commitment to technological innovation, policy reform, and responsible consumption. The ongoing depletion of finite stocks coupled with the escalating consequences of climate change demands immediate and decisive action. Future energy security hinges on the collective pursuit of a sustainable resource paradigm, ensuring both environmental integrity and economic prosperity for generations to come.