The central question regarding hydrogen’s role in sustainable power systems revolves around its origin. While hydrogen itself is the most abundant element in the universe, its availability as a usable energy carrier on Earth is more nuanced. The process of obtaining it requires energy input, and the source of that energy dictates whether it can be considered a sustainable option. Hydrogen is not a primary energy source found readily available for extraction like fossil fuels; it must be produced from other compounds. For instance, it can be derived from water through electrolysis or from natural gas through steam methane reforming.

The potential of hydrogen lies in its versatility as a clean fuel. When used in a fuel cell, it produces only water as a byproduct, offering a significant advantage over traditional combustion processes that release greenhouse gases and pollutants. Historically, hydrogen has been utilized in various industrial applications, but its widespread adoption as an energy source has been limited by the cost and carbon footprint associated with its production. Overcoming these challenges is crucial to realizing its full potential as a key component of a low-carbon energy future. Government policies and technological advancements are driving innovation in production methods, aiming to make it a viable and environmentally sound energy alternative.

The subsequent sections will explore the different production methods, their environmental impacts, and the overall viability of integrating hydrogen into existing energy infrastructures. Analysis will cover the distinction between green, blue, and gray varieties, highlighting the significance of sourcing in determining its sustainability. Furthermore, the discussion will address the challenges and opportunities associated with hydrogen storage, transportation, and utilization in various sectors, including transportation, power generation, and industrial processes.

Understanding the complexities surrounding hydrogen’s potential requires careful consideration of production pathways and their environmental impact. Evaluating its viability demands a holistic approach, examining both its benefits and the challenges it presents.

Tip 1: Differentiate Production Methods. Not all hydrogen is created equal. Distinguish between “green” hydrogen (produced from renewable energy sources like solar or wind), “blue” hydrogen (produced from natural gas with carbon capture and storage), and “gray” hydrogen (produced from natural gas without carbon capture). The environmental impact varies significantly depending on the method.

Tip 2: Scrutinize Energy Input. Remember that producing it requires energy. A truly sustainable system relies on renewable energy sources to power the production process. If fossil fuels are used, the overall carbon footprint may negate the benefits of using it as a clean fuel.

Tip 3: Assess Carbon Capture Efficiency. For “blue” hydrogen, carefully evaluate the efficiency of carbon capture technologies. Even with carbon capture, some emissions are inevitable, and the overall reduction in greenhouse gases depends on the capture rate.

Tip 4: Consider Infrastructure Requirements. The existing infrastructure for natural gas is not directly compatible with hydrogen. Significant investments are needed to develop new pipelines, storage facilities, and fueling stations.

Tip 5: Evaluate Lifecycle Emissions. Conduct a comprehensive lifecycle assessment that considers emissions from production, transportation, storage, and end-use. This provides a more accurate picture of the overall environmental impact.

Tip 6: Stay Informed on Technological Advancements. Advancements in electrolysis, carbon capture, and hydrogen storage technologies are constantly evolving. Keeping abreast of these developments is crucial for understanding its future potential.

Tip 7: Analyze Economic Viability. The cost of producing and distributing it remains a significant barrier to widespread adoption. Monitor trends in production costs and government incentives to assess its long-term economic feasibility.

Adopting these tips ensures a well-informed perspective on the role of hydrogen in the transition to a sustainable energy economy. A critical and nuanced understanding is essential for effectively navigating the complexities and maximizing the benefits of this energy carrier.

With these guidelines in mind, the upcoming conclusion will summarize the key findings and offer a final perspective on its potential and limitations.

1. Production Pathway

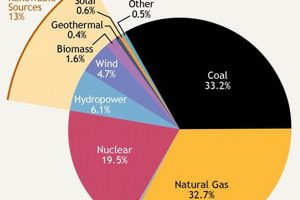

The production pathway fundamentally determines whether hydrogen aligns with the principles of renewable energy. This pathway dictates the source of energy used to liberate it from its compounds, such as water or natural gas. If the process relies on renewable energy sources like solar, wind, or hydro power to perform electrolysis (splitting water into it and oxygen), the resulting product is considered ‘green,’ signifying a potentially sustainable fuel source. Conversely, pathways utilizing fossil fuels, like steam methane reforming, generate ‘grey’, which is decidedly non-renewable due to the release of significant carbon dioxide emissions. Blue hydrogen, produced via steam methane reforming coupled with carbon capture and storage (CCS), aims to mitigate these emissions, but the effectiveness of CCS technologies and the potential for methane leakage upstream are critical considerations. The selection of the production pathway, therefore, is not merely a technical choice but a decisive factor in evaluating the overall sustainability of utilizing it as an energy carrier.

The impact of the production pathway extends beyond direct emissions. The construction and operation of production facilities, regardless of the chosen route, require resources and energy. A comprehensive life cycle assessment is essential to account for all associated environmental impacts, including resource extraction, manufacturing processes, transportation, and waste disposal. For instance, the mining of materials for solar panels used in green production or the infrastructure development for CCS in blue pathways must be factored into the overall environmental equation. This holistic approach allows for a more accurate comparison of different production pathways and informs decisions regarding the most sustainable options for incorporating into the energy mix.

In conclusion, the connection between the production pathway and the characterization of hydrogen as a renewable energy source is inextricable. While the potential of it as a clean fuel is significant, its realization hinges on the adoption of sustainable production methods. Prioritizing green pathways, rigorously evaluating the effectiveness of carbon capture technologies in blue production, and conducting thorough lifecycle assessments are crucial steps in ensuring that its use contributes to a genuinely sustainable energy future. Failure to address these aspects risks perpetuating reliance on fossil fuels and undermining efforts to mitigate climate change.

2. Energy Source

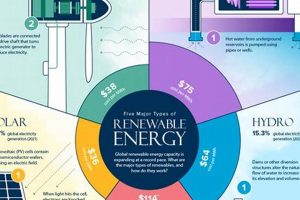

The origin of energy employed in its production is the singular determining factor in assessing its classification as a renewable energy source. The production of hydrogen, whether through electrolysis, steam methane reforming, or other processes, necessitates substantial energy input. If this energy derives from renewable sources such as solar, wind, hydroelectric, or geothermal power, the resulting it can be justifiably considered renewable. This is because the production process does not contribute to the net accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, aligning with the core principles of sustainable energy. For instance, a dedicated solar farm powering an electrolysis plant yields green hydrogen, a genuinely renewable fuel. Conversely, if the energy source is fossil fuels, the resulting product is not renewable, as the production process releases carbon dioxide and other pollutants, exacerbating climate change. Steam methane reforming, a common method, relies on natural gas and inherently results in significant carbon emissions unless coupled with highly effective carbon capture technologies.

The importance of the energy source is further underscored by the concept of lifecycle emissions. A comprehensive analysis considers all stages of production, from resource extraction to end-use. Even if the end-use of hydrogen is clean, producing only water vapor, the overall environmental benefit is negated if the production process involves significant fossil fuel consumption. Therefore, the pursuit of a hydrogen economy predicated on sustainability necessitates a concerted effort to transition towards renewable-powered production pathways. Government policies, technological innovation, and economic incentives play crucial roles in facilitating this transition. Investment in renewable energy infrastructure and the development of more efficient electrolysis technologies are essential steps in realizing the potential of as a renewable energy solution. Research into alternative production methods, such as biological processes or thermochemical cycles powered by concentrated solar energy, also holds promise for the future.

In summary, the relationship between the energy source and the categorization of hydrogen as renewable is direct and unequivocal. Only hydrogen produced using renewable energy can legitimately be considered renewable. A focus on renewable-powered production pathways, coupled with robust lifecycle assessments, is paramount in ensuring that it contributes to a sustainable energy future rather than perpetuating reliance on fossil fuels. The challenge lies in scaling up renewable production methods to meet growing demand and in addressing the economic barriers that currently favor fossil fuel-based production. Overcoming these hurdles is essential to unlock the full potential of hydrogen as a clean and sustainable energy carrier.

3. Carbon Footprint

The carbon footprint associated with hydrogen production is intrinsically linked to the question of whether it qualifies as a renewable energy source. The term “carbon footprint” refers to the total greenhouse gas emissions caused by an individual, event, organization, service, place or product, expressed as carbon dioxide equivalent. In the context of hydrogen, a large carbon footprint immediately disqualifies it from being considered renewable, regardless of its potential end-use benefits. For example, if is produced using steam methane reforming without carbon capture and storage, the process releases significant amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This high carbon footprint negates any claims of its sustainability, as it contributes to climate change rather than mitigating it. The fundamental principle is that a renewable energy source should have a minimal or net-zero carbon footprint throughout its entire lifecycle, from production to consumption.

The practical significance of understanding the carbon footprint is paramount for informed decision-making in energy policy and investment. Governments and businesses must prioritize production pathways that minimize emissions to truly leverage the potential of as a clean energy carrier. Blue , produced with carbon capture and storage, presents a lower carbon footprint compared to grey , but its sustainability hinges on the effectiveness of the carbon capture technology and the long-term storage integrity. Any leakage of methane during natural gas extraction or carbon dioxide during storage undermines the environmental benefits. Green , produced via electrolysis powered by renewable energy, offers the lowest carbon footprint and aligns most closely with the definition of a renewable energy source. However, the cost and scalability of green production remain significant challenges. Therefore, accurately assessing and minimizing the carbon footprint of each production method is crucial for determining the true value of it in a sustainable energy system.

In conclusion, the carbon footprint serves as a critical metric for evaluating the sustainability of . A low or net-zero carbon footprint is essential for to be considered a renewable energy source. Achieving this requires a shift towards green production methods and rigorous assessment of the effectiveness of carbon capture technologies in blue production. While faces challenges in terms of cost and scalability, prioritizing low-carbon production pathways is vital for realizing its potential as a key component of a sustainable energy future. The ongoing development and deployment of innovative technologies aimed at reducing its carbon footprint will be decisive in determining its ultimate role in the transition to a cleaner energy economy.

4. Sustainability Impact

The sustainability impact of hydrogen production and utilization is inextricably linked to its potential as a renewable energy source. Assessing this impact necessitates a comprehensive evaluation of environmental, economic, and social factors across the entire hydrogen value chain. The overall benefits of a hydrogen economy are contingent upon minimizing the negative impacts and maximizing the positive contributions to sustainability goals.

- Environmental Consequences of Production

Hydrogen production methods significantly influence environmental outcomes. Green methods, relying on renewable energy for electrolysis, minimize greenhouse gas emissions and environmental pollution. However, gray methods, utilizing fossil fuels, exacerbate climate change and contribute to air pollution. Blue methods, incorporating carbon capture and storage, offer a mitigation strategy, but the effectiveness of carbon capture and potential for methane leakage remain critical concerns. The choice of production pathway dictates the extent to which hydrogen contributes to or detracts from environmental sustainability.

- Resource Depletion and Land Use

Hydrogen production, regardless of the method, can impact resource depletion and land use. Electrolysis requires substantial water resources, potentially straining local water supplies, particularly in arid regions. The construction of renewable energy facilities, such as solar farms or wind farms, also necessitates land use, potentially impacting ecosystems and biodiversity. Responsible resource management and careful land use planning are essential to minimize the negative environmental consequences of hydrogen production.

- Economic Viability and Job Creation

The economic viability of hydrogen production and utilization is crucial for its long-term sustainability. High production costs, particularly for green hydrogen, can hinder its widespread adoption. Government subsidies, technological advancements, and economies of scale are essential to reduce costs and make hydrogen competitive with fossil fuels. The development of a hydrogen economy also has the potential to create new jobs in manufacturing, transportation, and energy sectors, contributing to economic growth and social well-being.

- Social Equity and Energy Access

The deployment of hydrogen technologies can impact social equity and energy access. Widespread adoption of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles could improve air quality in urban areas, benefiting public health. However, the affordability of hydrogen technologies and infrastructure development in underserved communities are critical considerations. Ensuring equitable access to hydrogen energy can contribute to social justice and reduce disparities in energy access.

The sustainability impact of hydrogen ultimately determines its viability as a renewable energy source. Prioritizing environmentally sound production methods, promoting responsible resource management, fostering economic viability, and ensuring social equity are essential to maximize the positive contributions of hydrogen to a sustainable energy future. A holistic approach, considering the full range of environmental, economic, and social factors, is necessary to realize its potential as a clean and sustainable energy carrier.

5. Lifecycle Analysis

Lifecycle analysis (LCA) is a crucial methodology for determining if hydrogen qualifies as a renewable energy source. LCA provides a comprehensive assessment of all environmental impacts associated with a product or service, from raw material extraction through manufacturing, transportation, use, and end-of-life disposal or recycling. In the context of hydrogen, LCA is indispensable because it moves beyond the point-of-use emissions (which are minimal when hydrogen is used in a fuel cell, producing only water vapor) to examine the entire value chain. For example, if hydrogen is produced through steam methane reforming (SMR) using natural gas, the LCA would account for the greenhouse gas emissions associated with natural gas extraction, processing, transportation, and the reforming process itself. Without carbon capture and storage (CCS), SMR yields hydrogen that, despite its clean end-use, carries a significant carbon debt, disqualifying it from renewable energy classification.

Furthermore, even in seemingly cleaner production pathways, LCA is vital for identifying hidden environmental burdens. Consider hydrogen production via electrolysis powered by renewable energy (green hydrogen). While the direct emissions are negligible, the LCA would evaluate the environmental impacts associated with manufacturing the electrolyzers, constructing the renewable energy infrastructure (solar panels, wind turbines), and the extraction of materials required for these technologies. The energy intensity of producing these components, the land use associated with renewable energy farms, and the potential for water scarcity in regions reliant on electrolysis must all be factored into a holistic assessment. The practical significance of LCA lies in its ability to reveal these upstream impacts, enabling policymakers and industry stakeholders to make informed decisions regarding the most sustainable hydrogen production pathways. For instance, an LCA might reveal that a particular source of renewable energy used for electrolysis has a higher environmental footprint than anticipated due to manufacturing processes, prompting a shift to a different renewable energy source or a different electrolyzer technology.

In conclusion, lifecycle analysis is indispensable for evaluating the true sustainability of hydrogen as a potential renewable energy source. It provides a rigorous and comprehensive accounting of all environmental impacts across the entire hydrogen value chain, enabling a more accurate determination of its carbon footprint and overall sustainability profile. The challenges lie in the complexity of conducting thorough LCAs and ensuring the availability of reliable data for all stages of production and utilization. However, the insights gained from LCA are essential for guiding investments, shaping policies, and promoting the adoption of hydrogen production pathways that truly contribute to a sustainable energy future. Without LCA, claims of hydrogen’s renewability remain unsubstantiated and potentially misleading, hindering progress towards genuine decarbonization goals.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries regarding the sustainability of hydrogen as an energy carrier, offering clear and concise answers based on current scientific understanding.

Question 1: Is hydrogen inherently a renewable energy source?

No, it is not inherently renewable. Its renewability depends entirely on the energy source used in its production. It is an energy carrier, similar to electricity, and its sustainability is determined by the origin of the energy used to generate it.

Question 2: What are the primary methods for producing hydrogen, and how do they differ in terms of sustainability?

The primary methods include steam methane reforming (SMR), electrolysis, and biomass gasification. SMR, which uses natural gas, is not renewable unless coupled with carbon capture and storage (CCS). Electrolysis, using electricity to split water, is renewable if the electricity comes from renewable sources. Biomass gasification can be renewable depending on the sustainability of the biomass source.

Question 3: How does “green” hydrogen differ from “blue” hydrogen?

“Green” is produced through electrolysis powered by renewable energy sources, resulting in minimal greenhouse gas emissions. “Blue” is produced from natural gas using SMR, with carbon capture and storage to reduce emissions. The sustainability of blue depends on the efficiency of carbon capture and the prevention of methane leakage.

Question 4: What role does carbon capture and storage (CCS) play in determining the sustainability of hydrogen production?

CCS can reduce the carbon footprint of produced from fossil fuels, but its effectiveness is crucial. The capture rate and the long-term security of carbon storage sites are critical factors. Even with CCS, some emissions are often unavoidable, impacting its classification as renewable.

Question 5: What are the key challenges to widespread adoption of hydrogen as a renewable energy source?

Challenges include the high cost of production, particularly for green methods; the need for significant infrastructure investment for storage, transportation, and distribution; and the energy losses associated with hydrogen conversion and utilization.

Question 6: How does lifecycle analysis (LCA) inform the debate about its sustainability?

LCA provides a comprehensive assessment of all environmental impacts across the entire value chain, from production to end-use. This analysis is essential for accurately determining the carbon footprint and overall sustainability profile of different production methods, highlighting both benefits and potential drawbacks.

In summary, whether it can be considered a renewable energy source is not a simple yes or no answer. A nuanced understanding of production methods, energy sources, and lifecycle impacts is essential for informed decision-making.

The following section will explore the future prospects for sustainable systems, including technological advancements and policy considerations.

Hydrogen

The preceding analysis underscores that the classification of “is hydrogen a renewable energy source” is fundamentally contingent upon its production pathway. While hydrogen itself possesses the potential to serve as a clean energy carrier, its actual sustainability hinges on the source of energy used in its creation. Green hydrogen, produced through electrolysis powered by renewable electricity, presents a genuinely sustainable option with minimal greenhouse gas emissions. Conversely, hydrogen produced from fossil fuels, even with carbon capture technologies, carries a significant carbon footprint that undermines its claim as a renewable resource. The complexities surrounding production, transportation, and storage necessitate a comprehensive lifecycle assessment to accurately determine the overall environmental impact.

The future role of hydrogen in a sustainable energy economy hinges on continued investment in renewable-powered production methods and the development of efficient, cost-effective technologies. Policy decisions, economic incentives, and technological advancements will be critical in shaping the trajectory of its adoption. A commitment to rigorous lifecycle assessments and transparent reporting of emissions is essential to ensuring that hydrogen contributes to a genuinely decarbonized future rather than perpetuating reliance on fossil fuels. Only through a concerted and informed effort can hydrogen realize its potential as a cornerstone of a sustainable energy system.