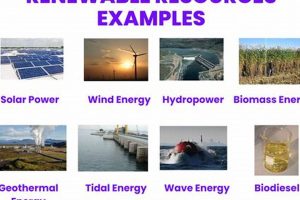

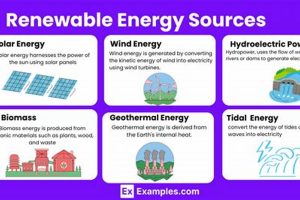

Energy sources are broadly categorized based on their replenishment rate. Resources that naturally replenish over a human timescale are considered inexhaustible. These include solar radiation, wind, and geothermal heat. Conversely, finite resources, formed over geological timescales, are exhaustible. Examples include fossil fuels such as coal, petroleum, and natural gas, as well as nuclear fuels like uranium.

The significance of understanding the difference between these energy categories lies in sustainable energy planning and environmental impact mitigation. Utilizing inexhaustible sources reduces reliance on finite reserves, lessening environmental degradation associated with extraction and combustion. Historically, societies have relied heavily on exhaustible resources, leading to resource depletion, pollution, and geopolitical instability. Transitioning to greater utilization of inexhaustible sources is crucial for long-term energy security and ecological preservation.

The following sections will delve into specific examples within each of these categories, exploring their characteristics, applications, and the environmental considerations associated with their use. Examination will also be given to the technological advancements driving the increased utilization of inexhaustible power options and the challenges that remain in achieving a fully sustainable energy future.

Guidance on Managing Energy Portfolios

The subsequent recommendations aim to facilitate informed decision-making regarding energy consumption and investment, emphasizing resource conservation and sustainable practices.

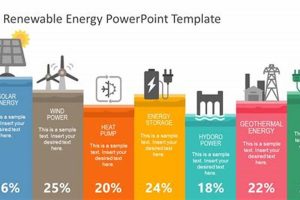

Tip 1: Prioritize Inexhaustible Energy Investments: Allocate capital towards infrastructure supporting solar, wind, and geothermal energy. These investments offer long-term cost savings and environmental benefits.

Tip 2: Implement Energy Efficiency Measures: Reduce energy consumption through building insulation, efficient appliances, and smart grid technologies. Lowering demand lessens reliance on all resource types.

Tip 3: Diversify Energy Sources: Mitigate risks associated with reliance on a single energy source by diversifying the energy portfolio. Include a mix of inexhaustible and, where necessary, finite resources.

Tip 4: Support Research and Development: Invest in research and development related to energy storage solutions and enhanced extraction techniques for finite resources (where ethically and environmentally sound). These efforts improve resource availability and grid stability.

Tip 5: Advocate for Policy Changes: Support policies that incentivize the use of inexhaustible sources and disincentivize unsustainable practices. Government regulations play a crucial role in shaping energy markets.

Tip 6: Conduct Lifecycle Assessments: Evaluate the environmental impact of each energy source throughout its entire lifecycle, from extraction to disposal. This holistic approach informs more responsible decision-making.

Tip 7: Consider Geopolitical Factors: Be aware of the geopolitical implications associated with different resources. Diversification can help reduce dependence on politically unstable regions.

Adhering to these guidelines promotes responsible resource management, fostering energy security and environmental stewardship. Implementing these strategies contributes to a more sustainable energy future.

The concluding section will summarize the key principles discussed and offer a final perspective on achieving a balanced and sustainable energy ecosystem.

1. Solar availability

Solar availability, the measure of solar irradiance at a specific geographic location, directly influences the viability of solar energy as a renewable resource. The amount of solar radiation received determines the potential energy output from photovoltaic systems or concentrated solar power plants. Regions with high solar availability, such as deserts and areas near the equator, are inherently more suitable for solar energy generation. This factor is critical in assessing the cost-effectiveness and overall contribution of solar power within a diverse portfolio of renewable and non-renewable energy resources. For example, large-scale solar farms are primarily located in sun-drenched areas like the southwestern United States, Spain, and parts of North Africa due to their significantly higher energy yields compared to regions with lower solar irradiance.

Furthermore, solar availability patterns, including seasonal variations and daily cycles, impact the stability and reliability of solar energy as a baseload power source. Grid infrastructure and energy storage solutions must be implemented to mitigate the intermittency associated with solar radiation fluctuations. Accurate forecasting of solar availability is essential for efficient grid management and integration of solar power into existing energy networks. Advanced meteorological models and satellite data contribute to these forecasting efforts, allowing utilities to anticipate and manage variations in solar energy supply. This integration requires significant investment in technologies such as battery storage, pumped hydro storage, and smart grid systems capable of balancing fluctuating energy sources.

In conclusion, solar availability is a fundamental determinant of solar energy’s role within the broader energy landscape. Its assessment is crucial for making informed decisions regarding energy infrastructure development, policy formulation, and technological innovation. Although solar energy is a renewable resource, its effectiveness hinges on understanding and adapting to the geographic and temporal variability of solar radiation. Overcoming the challenges associated with solar intermittency is essential for maximizing its potential and fostering a sustainable energy future.

2. Fossil Depletion

Fossil depletion represents a critical concern in the context of energy resource management, influencing global energy policy and investment strategies. The finite nature of fossil fuels necessitates a transition toward renewable alternatives, shaping the future composition of energy portfolios worldwide.

- Reserves and Production Decline

Extractable reserves of coal, petroleum, and natural gas are finite and subject to depletion. As easily accessible deposits are exhausted, extraction becomes more costly and environmentally damaging. Peak oil theory posits that global petroleum production will reach a maximum and subsequently decline, necessitating a shift towards other energy sources. This decline has significant economic and geopolitical implications.

- Environmental Consequences

The extraction and combustion of fossil fuels contribute to environmental degradation, including greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, and habitat destruction. These impacts necessitate the development and deployment of renewable energy technologies to mitigate climate change and improve air quality. Policies promoting renewable energy adoption often cite the environmental costs associated with fossil fuel use.

- Economic Implications

Fossil depletion influences energy prices and economic stability. As resources become scarcer, prices tend to increase, affecting industries and consumers. Investing in renewable energy infrastructure can reduce reliance on volatile fossil fuel markets and promote long-term economic growth. Furthermore, the renewable energy sector creates new employment opportunities and stimulates technological innovation.

- Geopolitical Considerations

Control over fossil fuel reserves has historically been a source of geopolitical power and conflict. As these resources diminish, countries reliant on fossil fuel imports face increased vulnerability. Diversifying energy sources through renewable technologies can enhance energy security and reduce geopolitical tensions.

The interconnectedness of reserves, environmental impacts, economic stability, and geopolitical dynamics underscores the urgency of transitioning away from fossil fuels. The imperative to mitigate fossil depletion drives investment in renewable energy technologies, shaping the future of energy production and consumption patterns globally. Addressing fossil fuel’s environmental and finite concerns necessitates a multifaceted approach involving technological innovation, policy intervention, and international cooperation.

3. Geothermal Consistency

Geothermal energy, a renewable resource derived from the Earth’s internal heat, is distinguished by its high degree of operational consistency. This characteristic differentiates it from other intermittent renewable resources and contributes to its strategic importance in diverse energy portfolios.

- Baseload Power Generation

Geothermal power plants can operate continuously, providing a stable baseload electricity supply. Unlike solar or wind power, geothermal energy is not subject to daily or seasonal fluctuations, ensuring a predictable and reliable energy output. This consistent supply is especially valuable for grid stabilization and meeting continuous energy demands. Geothermal plants in Iceland, for example, provide a substantial portion of the country’s continuous energy needs.

- Geothermal Heat Pumps (GHPs)

GHPs utilize the stable underground temperature for heating and cooling buildings. They offer consistent performance regardless of external weather conditions, providing energy-efficient climate control. GHPs demonstrate geothermal consistency at the local level, reducing dependence on variable renewable and non-renewable sources for residential and commercial heating and cooling.

- Resource Sustainability

Properly managed geothermal reservoirs can provide a sustained energy supply for decades. Responsible extraction practices and reinjection of geothermal fluids help maintain reservoir pressure and temperature, ensuring long-term resource viability. Sustainable management practices are crucial for maximizing the benefits of geothermal consistency over extended periods.

- Reduced Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Geothermal energy has low greenhouse gas emissions compared to fossil fuels. The consistent operation of geothermal power plants and GHPs contributes to reducing overall carbon footprint and mitigating climate change. Substituting geothermal energy for fossil fuels in base load power generation leads to significant and quantifiable reductions in carbon emissions.

The predictable and continuous nature of geothermal energy distinguishes it within the range of renewable resources. This consistency enhances grid stability and promotes energy security, contributing to the overall sustainability of energy systems when viewed in conjunction with diverse renewable and non-renewable energy sources.

4. Nuclear Waste

Nuclear waste is an unavoidable byproduct of nuclear fission, the process employed in nuclear power plants to generate electricity. While nuclear power is a non-renewable energy source, distinct from renewable resources like solar or wind, it plays a role in energy portfolios. The waste generated includes spent nuclear fuel and other radioactive materials that pose environmental and health hazards for millennia. The long-term management of nuclear waste is a significant challenge, inextricably linked to the sustainability and acceptability of nuclear power as an energy source. Examples of nuclear waste management strategies include deep geological repositories, where waste is buried in stable geological formations, and interim storage facilities, where waste is stored in pools or dry casks.

The connection between nuclear waste and the broader energy landscape lies in the trade-offs inherent in energy production. Nuclear power offers a high energy density and reduces reliance on fossil fuels, potentially mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. However, the creation of long-lived radioactive waste presents a substantial risk that requires careful consideration and mitigation. The decision to utilize nuclear power is therefore a complex calculation balancing energy needs, environmental impact, and the ethical responsibility to future generations. Ongoing research explores advanced reactor designs that produce less waste and waste treatment technologies that can reduce the volume and radioactivity of nuclear waste, but these are still under development and evaluation.

Ultimately, nuclear waste management represents a critical aspect of energy policy and resource allocation. The responsible handling of nuclear waste is essential for ensuring the continued viability and societal acceptance of nuclear energy as part of the energy mix. Furthermore, technological advancements in nuclear waste reduction and disposal are necessary to minimize the long-term environmental burden associated with this energy source. Addressing the challenges presented by nuclear waste remains a crucial component of pursuing a sustainable and balanced energy future, acknowledging both the benefits and risks associated with different energy resources.

5. Wind intermittency

Wind intermittency, a fundamental characteristic of wind energy, presents significant challenges to its integration into energy grids and its reliability as a primary energy source. Understanding the implications of wind intermittency is essential for evaluating the role of wind power alongside other renewable and non-renewable resources in energy systems.

- Variability in Wind Speed

Wind speed is inherently variable, influenced by weather patterns, geographic location, and time of day. This variability translates directly into fluctuations in power output from wind turbines. For example, a wind farm in a coastal region may experience significant output variations depending on the passage of weather fronts, impacting the stability of the electrical grid to which it is connected. The intermittent nature contrasts with the dispatchable nature of non-renewable resources like natural gas, which can be ramped up or down to meet demand.

- Grid Integration Challenges

Integrating wind power into electrical grids requires sophisticated management strategies to accommodate its fluctuating output. Grid operators must balance the supply of electricity with demand, and wind intermittency introduces uncertainty into this equation. Examples include implementing forecasting tools to predict wind power output and using fast-response backup generation to compensate for sudden drops in wind power availability. This often entails utilizing non-renewable resources like natural gas peaker plants, partially offsetting the environmental benefits of wind energy.

- Energy Storage Solutions

Energy storage technologies offer a potential solution to the problem of wind intermittency. Storing excess wind energy during periods of high wind speeds and releasing it during periods of low wind speeds can smooth out the overall energy supply. Examples include battery storage, pumped hydro storage, and compressed air energy storage. The economic viability and scalability of these storage solutions remain a critical factor in determining the future role of wind energy in meeting baseload power demands.

- Geographic Smoothing and Transmission

Connecting wind farms across a wide geographic area can reduce the impact of intermittency by averaging out local variations in wind speed. High-voltage transmission lines enable the transfer of wind power from regions with abundant wind resources to areas with high energy demand. For example, a transmission line connecting wind farms in the Great Plains of the United States to urban centers in the East can help balance regional variations in wind power availability. However, the construction of new transmission infrastructure faces regulatory and environmental hurdles.

The inherent variability of wind energy necessitates a holistic approach to energy planning that considers a diverse mix of renewable and non-renewable resources. Managing wind intermittency requires investments in grid infrastructure, energy storage technologies, and sophisticated forecasting capabilities. Successfully integrating wind power into energy systems depends on addressing these challenges and optimizing the interplay between different energy sources.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses common inquiries concerning the nature, utilization, and implications of different energy resource categories. The following questions and answers provide a concise overview of pertinent topics related to resource sustainability and energy policy.

Question 1: What distinguishes renewable resources from non-renewable resources?

Renewable resources replenish naturally within a human lifespan, exemplified by solar, wind, and geothermal energy. Non-renewable resources, such as fossil fuels and uranium, exist in finite quantities and are depleted through extraction and use.

Question 2: Why is the transition from non-renewable to renewable energy sources considered important?

The transition is driven by concerns over resource depletion, environmental degradation (including greenhouse gas emissions), and long-term energy security. Renewable sources offer a more sustainable pathway to meet energy demands.

Question 3: What are the primary limitations associated with renewable energy sources?

Intermittency, land use requirements, and initial capital costs are key limitations. Solar and wind power fluctuate based on weather conditions, requiring energy storage solutions or grid management strategies. Large-scale renewable energy projects may also necessitate significant land areas.

Question 4: How does energy storage address the intermittency challenges of renewable energy?

Energy storage technologies, such as batteries, pumped hydro, and compressed air, store excess energy generated during periods of high renewable resource availability. This stored energy can be released during periods of low availability, smoothing out the energy supply.

Question 5: What role does government policy play in promoting renewable energy adoption?

Government policies, including subsidies, tax incentives, renewable portfolio standards, and carbon pricing mechanisms, can incentivize investment in renewable energy infrastructure and accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels.

Question 6: What are the long-term environmental consequences of relying on non-renewable energy sources?

The extraction and combustion of non-renewable energy sources contribute to air and water pollution, habitat destruction, and greenhouse gas emissions, driving climate change and its associated impacts, such as sea-level rise and extreme weather events.

Understanding these distinctions and associated challenges is critical for informed decision-making regarding energy investments, policy development, and sustainable resource management.

The subsequent section will explore future trends and innovations in both renewable and non-renewable energy technologies.

Conclusion

The preceding analysis has elucidated the characteristics, implications, and interdependencies of various energy sources. A comprehensive understanding of types of renewable and non renewable resources is paramount for effective energy planning and mitigation of environmental risks. Examination of inherent limitations and benefits within each category facilitates responsible resource allocation.

Moving forward, sustained research, strategic investment, and international cooperation remain crucial for realizing a balanced and sustainable energy ecosystem. Acknowledging the finite nature of some resources and the variable nature of others underscores the necessity for innovation in both energy production and consumption patterns. Policy decisions enacted today will definitively shape the accessibility, affordability, and environmental impact of energy for future generations.